Demystifying the Inflation Question

A simple framework to answer the question - will there be inflation?

Will there be inflation? is a question that frequently comes up in conversation. As inflation is a stealth tax on one’s wealth, with escalating consequences once it increases above a comfort level of ~2% p.a, the fiscal and monetary interventions triggering this question rightfully makes people nervous. While I won’t pretend to know the outcome, this post lays out a simple framework that breaks the question down into its individual parts and answers each part individually, providing some intuitive guidance as to where the journey could go. Again, the focus is on the US as the center of gravity of the economic world.

Inflation occurs when there is more Demand for goods and services than there is Supply and prices move up in order to create an equilibrium. Technology has a deflationary effect, Demographics are also an influence, as is Market Concentration. Commodities play less an important role than commonly thought. Hyperinflation is when the whole thing gets out of control. Inflation can also occur when prices are increased as a reflex, because people got used to a high inflation context, even though the reason for a supply/demand imbalance has fallen away (Stagflation). Finally, there is Asset Price Inflation.

Starting with the Supply of goods and services. Inflation occurs when supply is hampered in its ability to serve demand. This can be Temporary or Permanent.

Temporary supply constraints can originate from obstacles to shipment or production:

For example, COVID-19 required social distancing on factory floors, so factories have reduced output capacity; shutting Iran out of the global oil market reduces the amount of oil on the market; US-tariffs on Chinese goods increased their cost

Temporary supply constraints can also stem from a sudden and unexpected surge in demand:

As economies reopen, demand returns faster than anticipated. Producers take time to re-tool their factories and re-hire staff to accommodate higher demand. As a consequence, producer prices go up. The opposite effect happens when demand collapses following the introduction of lockdowns

Because of advances in technology, efforts to adjust production to higher demand take much less time than in the past. Tesla needed less than a year from starting construction of their Shanghai factory (Jan ‘20) to the first vehicle produced (Nov ‘20), with annualised output to reach 500k vehicles this year. For the BMW factory in Dingolfing, Bavaria, it took from 1967 to 1973 to start production, at a much lower operating capacity thereafter

Permanent supply constraints are found when current supply cannot be expanded or can only be expanded slowly:

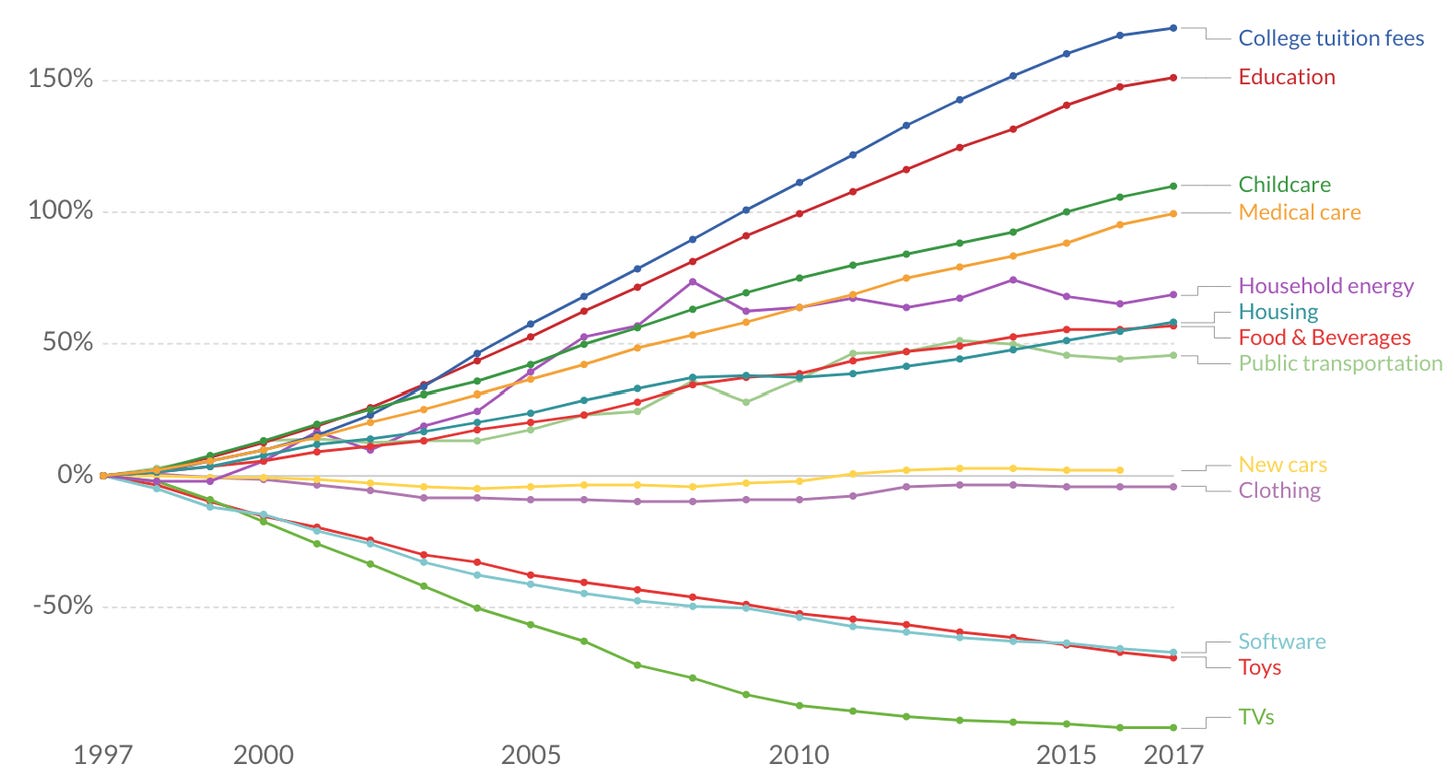

This can be seen in the luxury sector, where higher pricing power for the affluent led to a rise in demand for goods that are scarce. There are only so many luxury hotels on Capri, only so many Hermes Birkin bags, and only so many private schools or colleges with a 100 year+ history

Evolution of various US Inflation (CPI) components since 1997

Finally, supply constraints can assume more of a permanent nature if the economy is running at full capacity and there are not enough people to fill roles, and those roles cannot be substituted by offshoring or automatization

When this occurs, the so-called output gap is filled. This hasn’t been the case in decades, but may change going forward as policies change (see next point)

Currently, for the vast majority of goods and services, supply constraints are temporary and any inflation stemming from those will likely be transitory

Inflation can also be driven by the Demand side. Demand for goods and services is driven by how much money people have in their pockets:

Because globalisation erased wage bargaining power for the Western Middle class, wage growth for the average person has been anaemic. Consequently, as people didn’t have more money, they couldn’t spend more

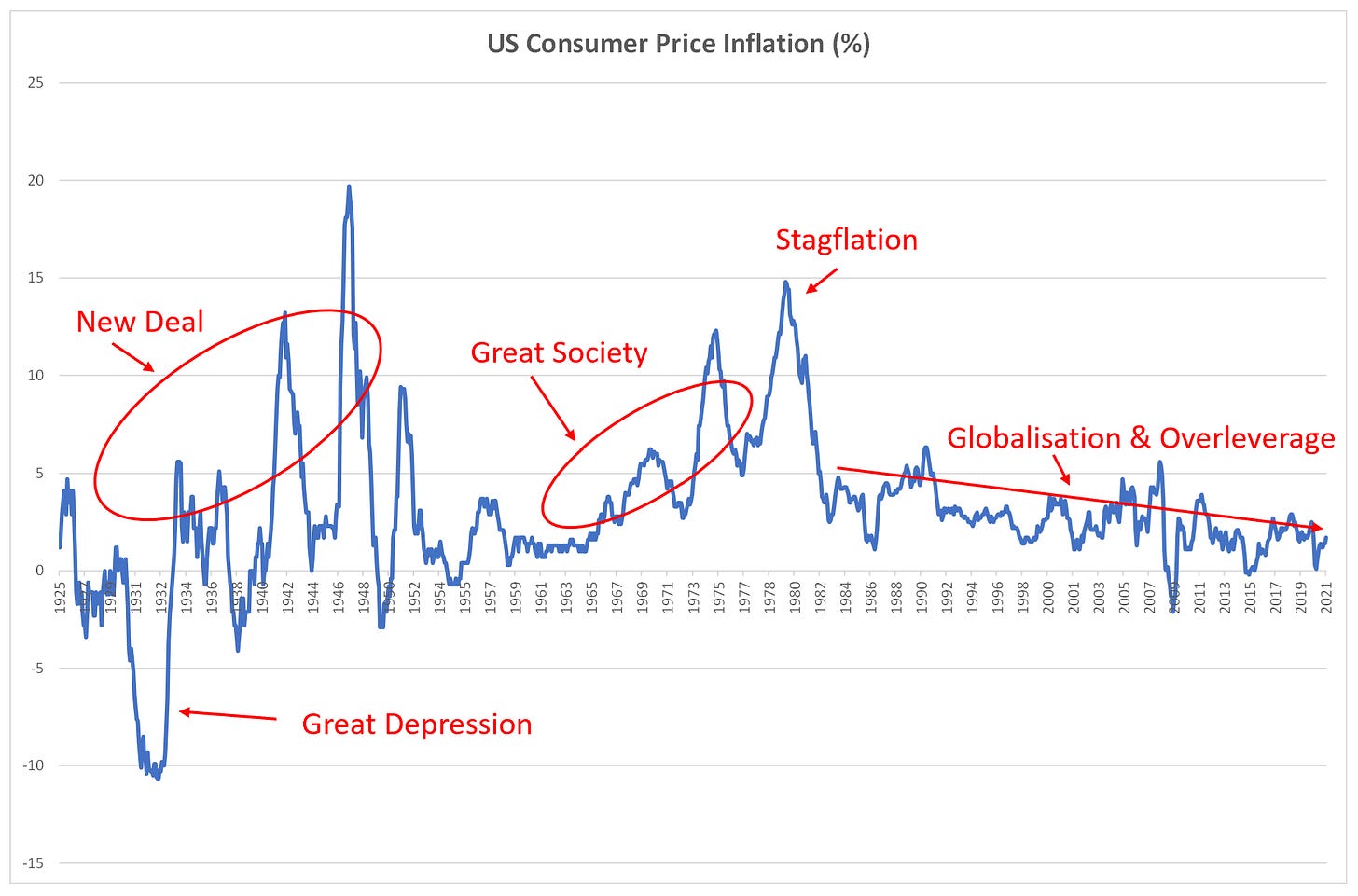

Accordingly, demand pressures on inflation haven’t really existed throughout the past decades. The last time this occurred was in the ‘50s and ‘60s, following the Great Society program by L.B. Johnson (the ‘70s were shaped by stagflation, see below)

It is the intention of both the new US administration as well as the Federal Reserve to change this dynamic. Bringing wage bargaining power back to lower-income groups (and thereby to the entire wage body) is an explicitly-stated goal, as discussed in a previous post. Budget deficit as well as inflation concerns have become secondary nature, overcorrecting from past learnings

Testament to this change in mindset are the 1.9tr COVID-19 stimulus package which deliberately risks overheating an already reopening economy, as well as the 3tr infrastructure stimulus currently proposed

It remains to be seen, whether and how quickly these goals are achieved. There are some signs that the US labor market is already tight, with companies struggling to fill positions and consequently shifting to higher wages to achieve their goals

Should the US be successful in establishing this paradigm shift, wages will increase and people will have more money in their pockets. No matter any deflationary tendencies on the supply side, this means more money to spend on whatever goods and services are around (For economists, this would be re-establishing NAIRU and the Philips Curve). In other words, it is very possible that this policy shift affecting the demand side will lead to higher inflation

Turning to several secondary factors playing a role in inflation

Technology has a deflationary effect as innovation makes processes more efficient, and this effect is accelerating. However, we continue to use upgraded products, so the effect is mainly visible in improved product performance, rather than lower prices for old products:

The first 3G iPhone in 2008 was priced at ~$700, its price fell to $500 within two years, and today could be found for roughly $20 if anyone cared to buy it. But what people want to buy is the new product, and the current iPhone 11 Pro Max costs $1400. It has 20x more memory, 2 more high definition cameras and 5G speed

Demographics plays a role. When the working population grows slower than the retired population, demand falls as retirees consumer less on average than these younger parts of the population. This is then compounded by oversupply as the production capacities were built to service a previously larger working population (now retirees). The effect is very pronounced in Japan, visible in Southern Europe, and may also eventually reach the US as birth rates decline

Commodities are often referred to in discussions around inflation. In recent history however, their effect was minor. As an example, oil only has a 0.27 correlation to consumer price inflation; the commodities boom from 2003-08 had no impact on inflation, even though several commodities multiplied in price

Market concentration, where very few companies have very high market shares in a given sector, affords suppliers more pricing power. Concentration has increased over the past 40 years as anti-trust offices have accommodated consolidation. In many tech sectors, there is a strong gravitational pull towards a winner-takes-all state. Just think of the prices that Google charges for its online ads

All these effects play a role, however they are superceded by the demand dynamics discussed above. In the end, it is the amount of money in peoples’ pockets that determines how much can be spent

Finally, turning to three particular variations of inflation

Hyperinflation occurs when the supply side is massively impaired due to an extreme shock to the system, while at the same time the government prints money to continue paying people’s salaries. In Weimar Germany in 1923, the French occupation of the Ruhr area took away most of the productive capacity of the country. In Zimbabwe in the late 1990s, the eviction of white farm owners led to food output falling by ~70%. This is an unlikely scenario for the Western world today as, even with COVID-19, production was never as dramatically impaired and government subsidies are only a fraction of those in these historical examples

Stagflation occurs when companies increase their prices because they expect inflation to continue in the period ahead, even though there is no demand pressure as slack in the economy is high and many people are unemployed. This kind of behavior requires many years of past inflation to have engrained expectations of higher inflation in peoples’ minds. Today, with 40 years of deflationary circumstances, we are very far from that state

Asset price inflation refers to the dramatic increase in value of many financial assets over the past decade. Much of this was closely linked to the equally dramatic reduction of interest rates as well as the acquisition of government debt by central banks. As the average person only holds a limited amount of assets, the positive effects from this dynamic only had limited effects on broad demand

However, if inflation increases in the next few years and interest rates follow in log step, there will likely be a counterintuitive negative effect on the value of rate-sensitive assets such as real estate (especially in regions where it has become detached from its intrinsic value and mainly been acquired to “park” money that would have otherwise been invested in government bonds)

In summary, yes, the inflation question is very complex to answer. However, looking at the individual building blocks, and in particular the demand side, it is fair to say that the risks are more skewed to the upside than they’ve been for a long time. We may see more inflation going forward, which would be a novelty after four decades of trends in the other direction.

Couldn't have picked a more appropriate title. Always helpful to have the major issues set out in one place. Thank you.

I really enjoyed this article, especially the part about hyperinflation