3% is not Enough

Why interest rates are likely to again move higher from here

In last week’s post I described how the investing landscape has changed, with US government bond yields as key driver of all asset classes. Since the beginning of the year, these have risen considerably (US 10-Year yield from 1.5% to ~3%), driving much of the turmoil in equity markets, to then stall their ascent.

However, various recent datapoints indicate that inflationary pressures remain strong. As such, another upwards move in US government bond yields is likely. This post explains the reasoning behind this assumption, and its implications for markets, which are likely profound

Inflation is an insidious animal, easy to conjure and very hard to get rid of. This historical stereotype seems once again confirmed. Three recent datapoints indicate that the Fed’s efforts to get it in check are still not enough. Let’s walk through them:

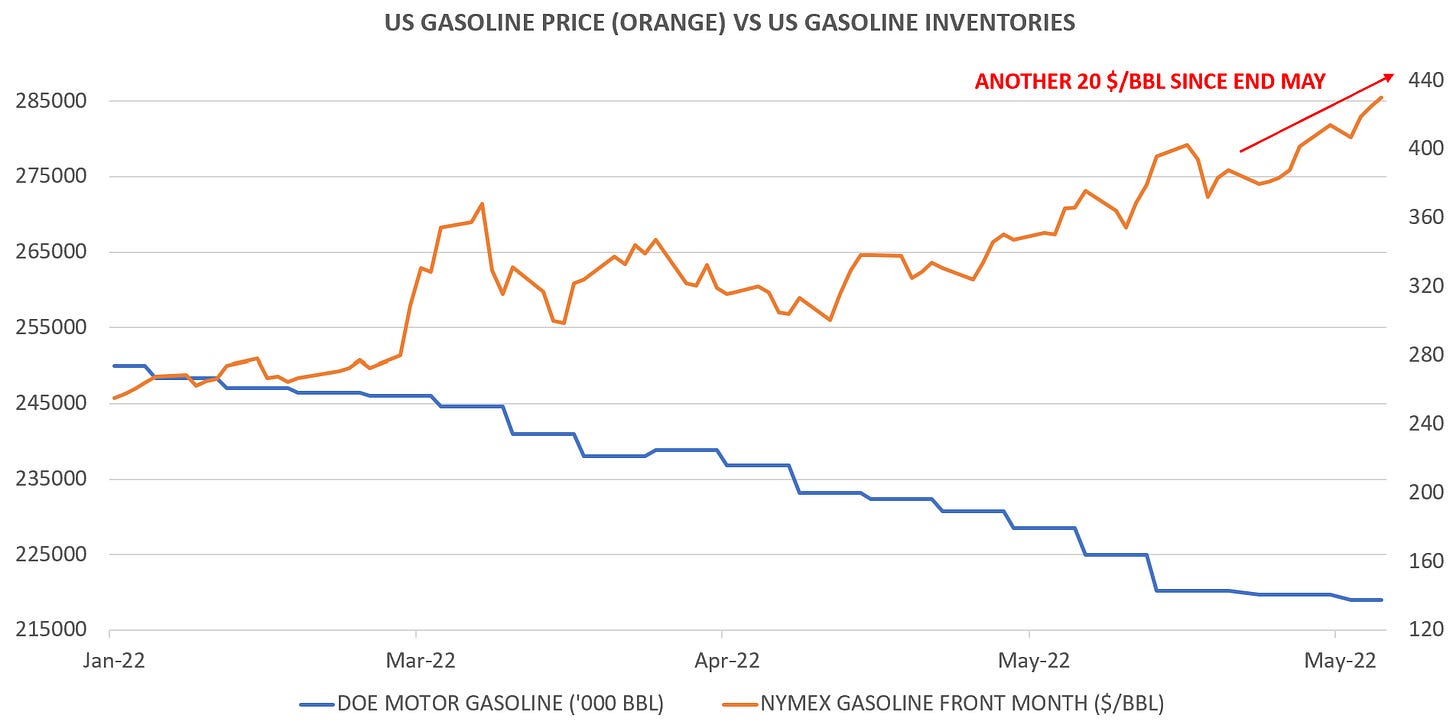

1- Gasoline

At the risk of repetition, I cannot stress the importance of this issue enough. This is the financial world’s most important metric right now

The price of US gasoline reached another record high over the weekend as both the oil price and refining spreads increased further (gasoline = oil + refining margin)

Over Covid, US refining capacity has been shut. Now, demand is back, and imports from Russia or China that could fill the gap are gone

In the United States, public transport options are limited. You need to drive. Gasoline is the fundamental ingredient required to participate in society

With each gas station advertising its price prominently on big panels, any changes are front of mind. As such, higher prices immediately translate into the political debate

There isn’t enough refining capacity, there isn’t enough oil, there is no supply response, so there is no respite in sight.

OPEC+ is not in a place to solve this, it has been lagging behind its own growth targets for months. Saudi oil minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, who’s been around since the 1980s, summarises it well:

The only way for the gasoline price to come down is for demand to come down. Gasoline prices that increase at an accelerated pace are an indication that aggregate economic demand is still much too strong

2- Rents

Aside from food and gasoline, shelter is the other category that fulfils basic needs. Rents represent ~30-40% of the Consumer Price Inflation basket

In spite of tighter financial conditions, the cost of rent accelerated to a 1.2% month-on-month increase in May

Shelter (as measured in “Owner-Equivalent Rents”) contributes to the CPI with a ~12 months lag. The fact that rent is still accelerating means we likely face many months with still uncomfortably high CPI prints

Now, many argue that there is not enough housing inventory, so there is not much that could be done. I find that unlikely. Population grew slower than housing units since 2019, and back then there was no inventory issue

It seems more likely to me that investment into real estate to replace government bonds, as well as smaller household sizes due to increased wealth during the pandemic are really driving this tightness1

In other words, I don’t think housing has an inventory problem. It rather seems it still has an excess money supply problem

The acceleration of rental costs in May is another indication that there is still too much money floating around

3 Labor Market

This past Friday’s NFP data reported another 325k jobs created in the US in May. At the same time, job openings remain at an historically elevated level

With this, I am referring to the JOLTS job openings data, which showed 11.4m positions for April, or a ratio of 2 vacancies per 1 unemployed, vs ~0.5 to 1 historically

Official data is only available for April, however JOLTS correlates strongly with Indeed’s job openings which remained elevated for May. This implies no material near-term changes (On the side - this serves as a good nowcasting illustration as discussed in my last post)

Further, it was noticeable in Friday’s jobs data that the 325k new positions were filled by workers returning to the labor force (i.e. they had previously registered as “not looking for work”)

While this is generally good, in an inflationary economy it simply means more salaries paid and thus more money to go around in a supply-constrained economy. In other words, this contributes to higher inflation

I had written about the much-discussed ratio of unemployed to vacancies already back in August 2021. It continues to indicate an extremely tight labor market, still very far from a state that would alleviate inflationary pressure

While these three datapoints indicate that demand is still too strong, at the same time, many Americans feel the pinch. They are cutting back on non-essential expenditure, as recent earnings by Walmart and Target testify. How can this be reconciled?

First, at the root of inflation is the enormous cash pile on the aggregate US consumer balance sheet, which so far has barely been reduced:

Second, this “mountain of cash” is very unevenly distributed. In fact, the bottom quintile has already spent it, while the rest is still hanging on to most of it

So the seeming dissonance between demand still being too strong, and many having to cut back is explained by the same pattern inside the US, as we can witness on a global stage

On a global stage, rich countries like the US and Western Europe squeeze poor emerging markets like India, Pakistan, or Sri Lanka in the competition for scarce resources

Inside the US, the poor are squeezed by the ones who are better off in the competition for scarce shelter, gasoline and also food

Conclusion: Despite recent tightening in financial conditions, there are many signs that inflationary pressures are still too high. Inflation is America’s number 1 concern and the Fed has stated its resolve to fight it on many occasions. Therefore, expect another leg-up in both Fed rhetoric and action, and consequently higher US bond yields

The question is, how high would yields have to go to put inflation back in the bottle?

The technical answer is that “real yields”, i.e. nominal yields minus inflation expectations would have to be meaningfully positive (say 1-2%). This would incentivise the private sector to save instead of spending or levering up, redirecting the “cash pile” away from consumption. 10-Year real yields are currently at 0.2% (= 3% 10-Year Yield minus ~3% 10 Year inflation expectations), this implies 4-5% for the US 10-Year

There is also a practical answer: Ask yourself, at what interest rate would you be comfortable to put your cash into US 10-Year government bonds? For me, the answer is 4-5%, assuming I could get conviction the US is serious about killing inflation

What does this mean for markets?

Higher US Treasury yields are negative for all risk assets. This comes on top of downgrades to corporate earnings, as cost inflation eats into margins

Despite the 14% YTD drawdown in the S&P 500, I am hard-pressed to find any interesting opportunities to deploy cash on the long side, whether it is bonds or equities. As indicated last week, I have now further increased shorts in cyclical sectors, including XME (Materials), and also added shorts in TLT (long-term bonds)

Oil is the one exception. There is no supply response in sight, and the trend continues to be up until enough demand destruction has occurred. I don’t know where that point is, but it does not seem imminent. I am watching this and gasoline as key metric to confirm or negate my view on higher bond yields

While the US private sector - on aggregate - is swimming in cash, there are many pockets of excess leverage, from US commercial real estate to Buy Now Pay Later, German real estate, European Government debt or many parts of Private Equity. Accordingly, it seems likely to me that next years will provide much opportunity in Distressed Debt

If rates continue to increase, this will also put pressure again on high-duration assets such as the Nasdaq. In this area, China Tech (FXI/CQQQ/KWEB) seems a bright spot, with the Chinese government turned supportive (e.g. DIDI ban on new users lifted) and low valuations. If you believe the market goes up, this is likely your fastest horse. I remain cautious

With regards to the structure of this current market decline, I read many analogies to the 2000-2001 and 2007-2008 bear markets, which were drawn out and with multiple periods of relief, where markets went up for weeks, or even months

I find the analogy to 1973 much more compelling. In the preceding years, excessive money printing first created the nifty-fifty stock market boom which saw elevated valuations for growth stocks

It was then followed by high inflation, the Yom-Kippur war and the Oil embargo which pushed Western economies into recession

The corresponding bear market extended over a much shorter period of time, with only brief periods of respite

We are likely still in the middle of a severe downturn. Cash remains king. Please keep in mind, asset price deflation and consumer price inflation can occur simultaneously

You won’t protect your cash from inflation if you buy assets that decline in value, and right now the Fed wants and needs asset prices to go down

Please see previous post “Crash, Inflation Hedge or Nothing to See“ for more details on US housing

Super clear post on a complex subject

Quality.