A Flashing Warning

Revisiting the Inflation Question

Inflation is the biggest risk for the economy and warrants very close attention. Consensus is that the current elevated readings of +5% p.a. for US Consumer Price Inflation (CPI) will prove transitory. However, many data points especially in the US labor market speak another language and cannot be ignored. After assessing in April that risks are skewed to the upside, I’ve now revisited the topic, with my conclusions below. I believe consensus is wrong and serious concerns are now warranted

First of all, let’s recall why the question of inflation is so important

Higher prices for everyday goods and services make everyone’s lives more difficult. This is particularly true for lower income earners who spend most of what they earn

The financial system has employed leverage extensively, enabled by low interest rates. If interest rates had to rise in order to combat inflation, that would therefore have profoundly negative effects on asset prices

While the government and central banks can fight deflation by stimulating the economy, inflation has to be fought by slowing the economy, which can be a very painful process

And where do we stand currently?

When the economy re-opened post COVID-19, money saved during lockdowns as well as trillions of USD of government support provided the fire power for an unprecedented spending boom

With supply chains unprepared for this demand shock, inflation ensued, with the latest readings >5%

The common assumption is that these unusually high levels are “transitory”:

Supply chains would adapt over time while demand should cool from re-open enthusiasm

At the same time, the deflationary forces that dominated the past decade would still be around (declining demographics, excessive leverage, technology)

Unemployment levels are still high, accordingly there would not be any pressure on employers to increase wages substantially

This last point is the most important. For inflation to become persistent, you really need wage growth to happen1

It’s very simple: if wages don’t grow, people don’t have enough money in their pocket to pay up for more expensive goods and services. In a self-regulating way, demand declines again, thereby moderating inflationary pressures

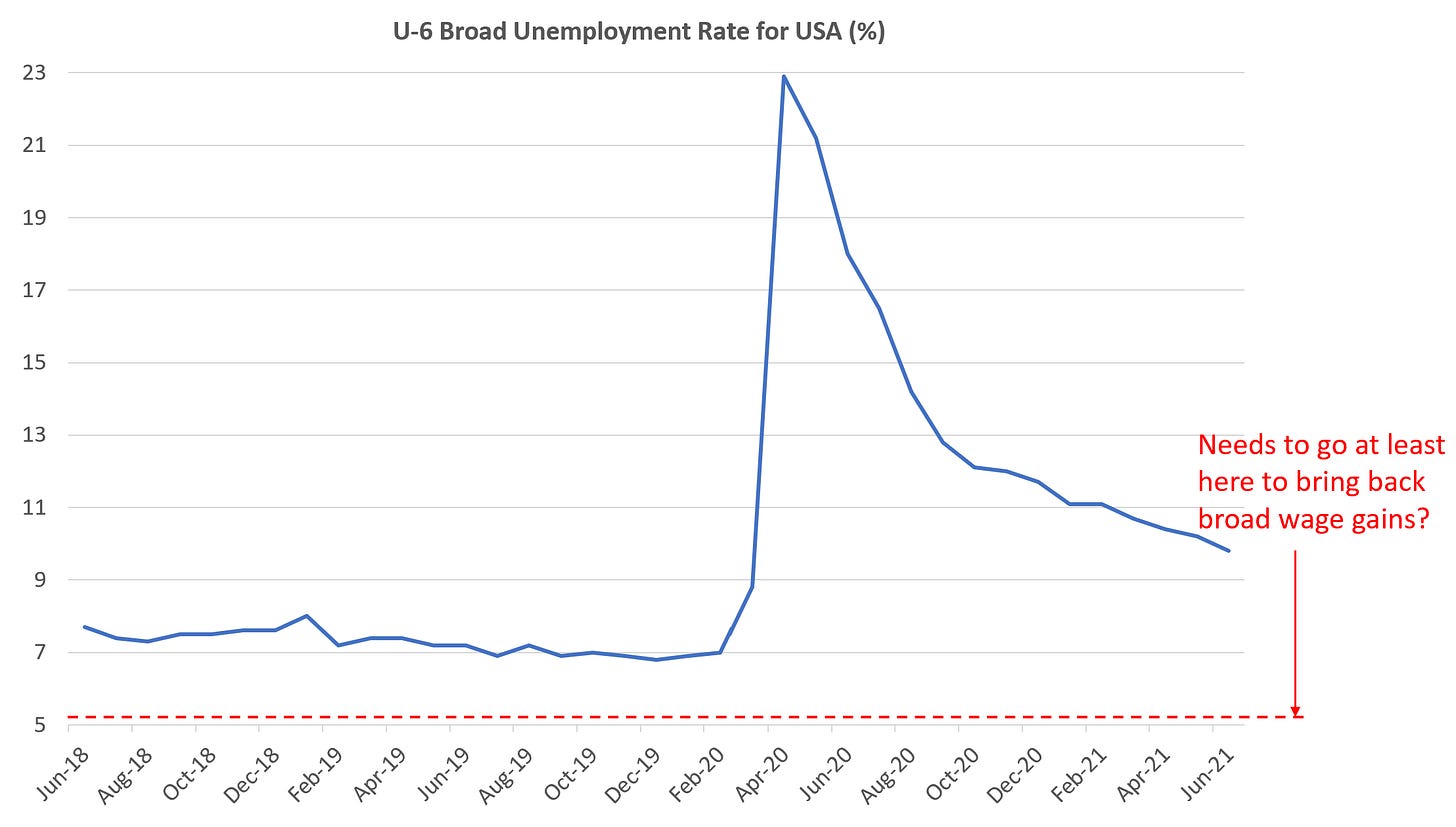

As of now, the official unemployment rate in the US is 5.5%, and the Fed’s broader measure of unemployment, stands at 10%

The broad measure includes people who are in working age, but for whatever reason aren’t actively looking for work

Looking at these unemployment statistics, yes, it seems that we are far from an overheated labor market. No upward pressure on wages, no lasting inflation concerns, transitory, done

However, forgetting this traditional relationship between inflation and unemployment for a moment, and just applying some common sense to what the situation “on the ground” tells us, the picture seems very different

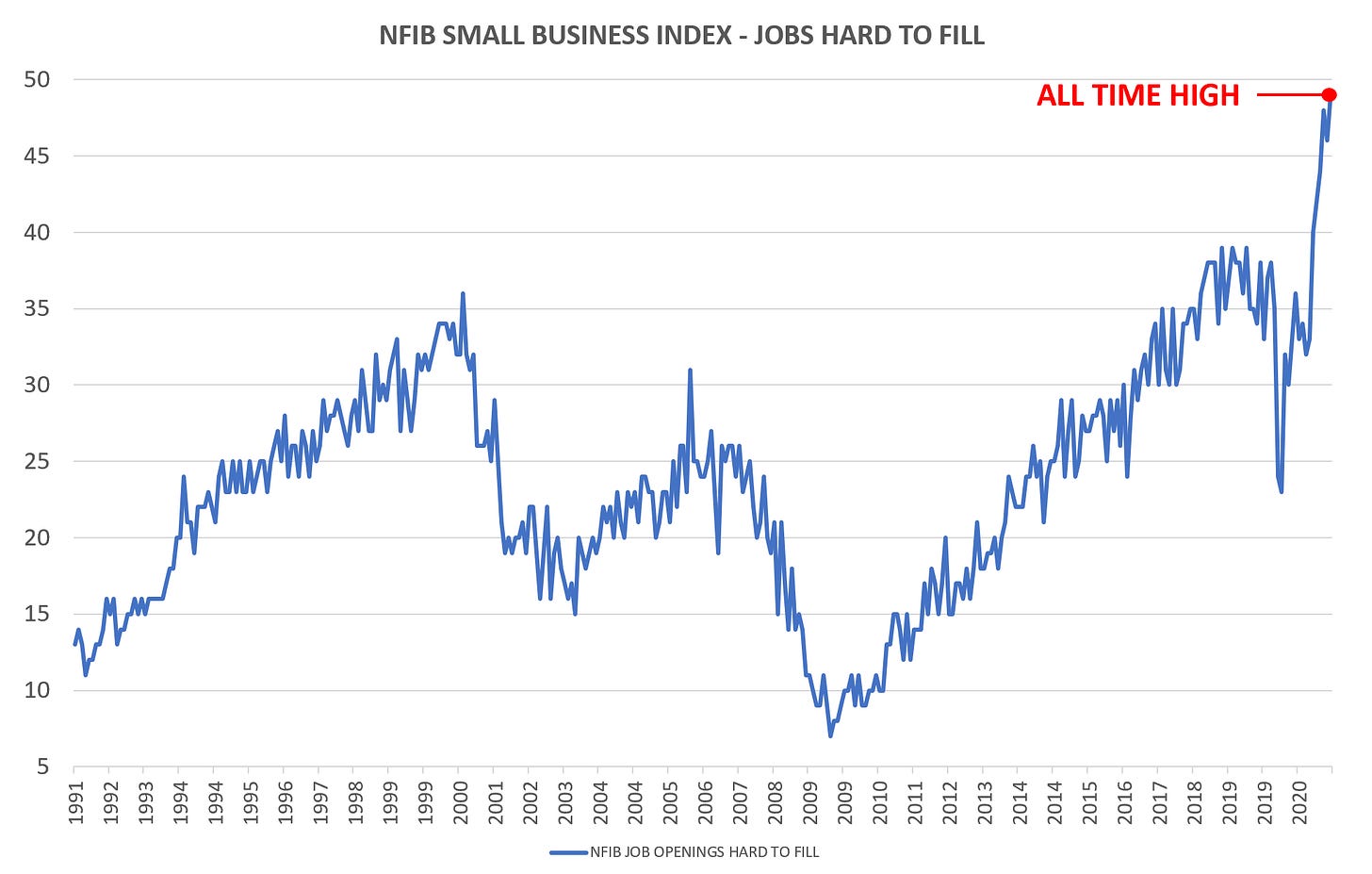

Despite a 10% broad unemployment rate, businesses are struggling like never before to fill roles:

The ratio of job openings to unemployed is near a multi-decade high:

More so, the rate of people quitting their jobs is at an all-time high

This is traditionally highly correlated to a tight labor market. If you have plenty of other options, you are more likely to jump ship

Historically, the quits rate has been a good lead indicator of wage growth

With these data points in mind, unsurprisingly, there is plenty of anecdotal evidence of staff shortages and wage increases:

Staff shortages are reported in many industries ranging from airlines to fastfood to farming

There is a global truck driver shortage, as reported e.g. here and here

Many companies are raising wages to retain staff, such as e.g. Walmart, Amazon, CostCo or Lululemon

In summary, the picture “on the ground” is entirely different to what the unemployment data tells us. In fact, it screams of an overheating labor market

But how does this reconcile with the high unemployment rate? In theory, there should be a deep reservoir of people willing to pick up these jobs, alleviating all these signs of pressure

Now, several observers have pointed to continued unemployment benefits as a reason

I find that unconvincing and believe while this may apply to some, most people want to work rather than sit at home

In my view, the main reason is a mismatch in skills that has been created by the unusual nature of the COVID-19 recession, and then massively exacerbated by the unprecedented government stimulus

COVID-19 was not a “normal” recession, it was more of a temporary freeze in activity for parts of the economy

In the last big recession in 2008/9, unemployment hit everyone, from the waitress at Wendy’s to the investment banker at Goldman Sachs

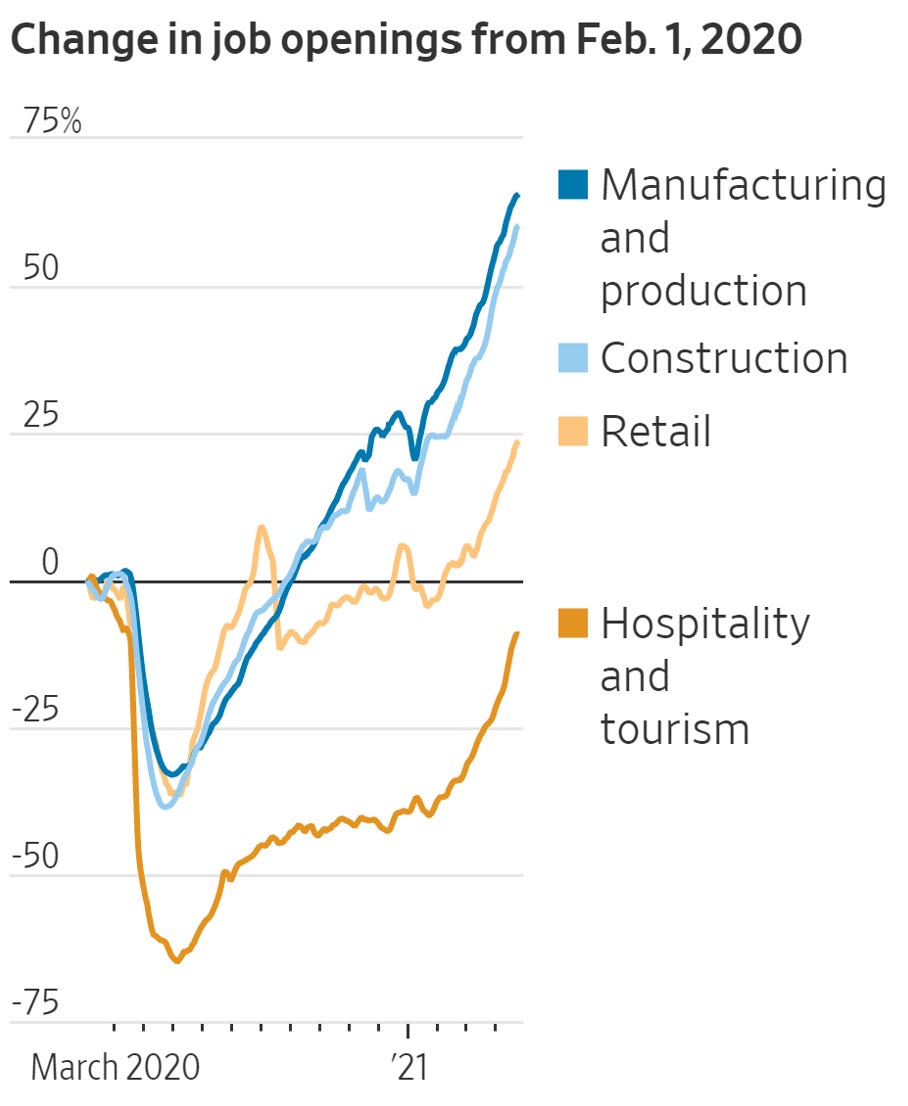

This time, the effect was very uneven. COVID-19 caused some segments like hospitality to grind to a total halt. But others saw only mild demand declines that reversed quickly, or even increases

In addition, as activity resumed once lockdowns passed, it proved to be a very brief “recession”, in fact the shortest on record

Into this backdrop, a historically unprecedented amount of government support was unleashed, almost 6x the size of the Great Financial Crisis of 08/09 despite much less structural economic damage (!!)

In fact, the only two sectors that really needed big bailouts were hospitality and Wall Street, which would have melted down in a sequence of margin calls without intervention, given the high leverage in the financial system (Think about that…)

Now, let’s look at the chart below. How has the labor market developed for various industries since the start of the pandemic?

Two things stand out. There are big divergences between sectors, and some areas like manufacturing and construction are very hot, with demand way above an already healthy late-2019 level

This uneven development contributes materially to the mismatch in skills

As an example, if you were working in hospitality in California, you can’t just become a truck driver in the North East overnight. Licences, regulation and family ties are all reasons that limit flexibility

We are facing an uneven labor market where large parts are already much hotter than the unemployment rate suggests. This will fuel inflationary pressures going forward

However, the effects of the overblown stimulus policies go beyond the labor market

As a consequence of booming demand, inventories in many industries are at all-time-lows

An example is the car industry, which in addition has to deal with chip shortages that are still getting worse

The inventory levels of the US car industry are at historically low levels, everything is sold out!

And what does a company do whose inventory is empty? It raises its prices…

More so, the continued easy money policies in the face of a booming economy have now created a spill-over mechanism from asset-price-inflation to CPI-inflation

House prices in the US are going parabolic, supported by low interest rates and quantitative easing

As house prices become too high in comparison to salaries (discussed before here), people can’t afford to buy anymore and are forced to rent

This means considerable upward pressure on rents going forward. Shelter typically represent a quarter of household expenses and thus CPI, so an increase in shelter costs will translate into a higher CPI

This will be very painful for many people in lower income brackets

All this illustrates a general problem with Central Bank intervention. The economy is an incredibly complex and ever-changing organism. It is very hard even for a group of very experienced economists such as central bankers to accurately assess the impact of their actions

The unintended consequences create new issues which are then tackled with more intervention, creating more unintended consequences and so forth

This reminds of the poem called The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (“Zauberlehrling”) by Goethe, made into the Disney movie Fantasia in 1940 where a Mickey Mouse turned sorcerer cannot control the spirits he summoned anymore

Conclusion:

The US economy and its labor market show significant signs of overheating, while the side effects of excessively easy monetary policies continue to distort economic activity

In the very near term, this translates into strong economic data, providing the backdrop for the current parabolic “everything-rally”, which has more legs given the pervasive sceptic sentiment and light positioning. Cyclicals and commodities should lead from here, while long-duration assets (speculative tech etc.) should lag

Gold should also benefit as the topic gradually comes back to the forefront

Looking further out, the picture is different - I assign a high likelihood of an inflation scare within the next half a year as the pin pricking the bubble

More so, there is a significant risk that the Fed will eventually face the choice between rising rates and thereby tanking the market or letting inflation run further. Given the historical sensitivity to inflation, the Central Bank would very likely choose rising rates

This would be negative for all assets, the more leverage and the longer in duration, the worse. The best protection against this scenario is a high cash position, or exposure to de-correlated assets (see for example my recent post on Chinese Internet, where monetary policy is deliberately going a different direction)

To be precise in economic terms, in order to create inflation, real wage growth needs to outpace productivity gains, which would be the case once labor becomes scarce and competitively bid. If productivity gains are strong, wages can rise in lockstep without causing inflationary pressure. In the current situation, wage increases are caused by excess liquidity, not productivity gains