A Generational Low?

Why interest rates might turn now and not revisit their lows for a very long time

The future is complex and uncertain. Accordingly, any statements about future events can only be expressed in conditionals and probabilities. That being said, the probability for structural economic changes has risen significantly. With politics prioritising economic growth over inflation for the first time in four decades, interest rates may reset to structurally higher levels, thereby altering the make-up of the economy. The case is laid out below

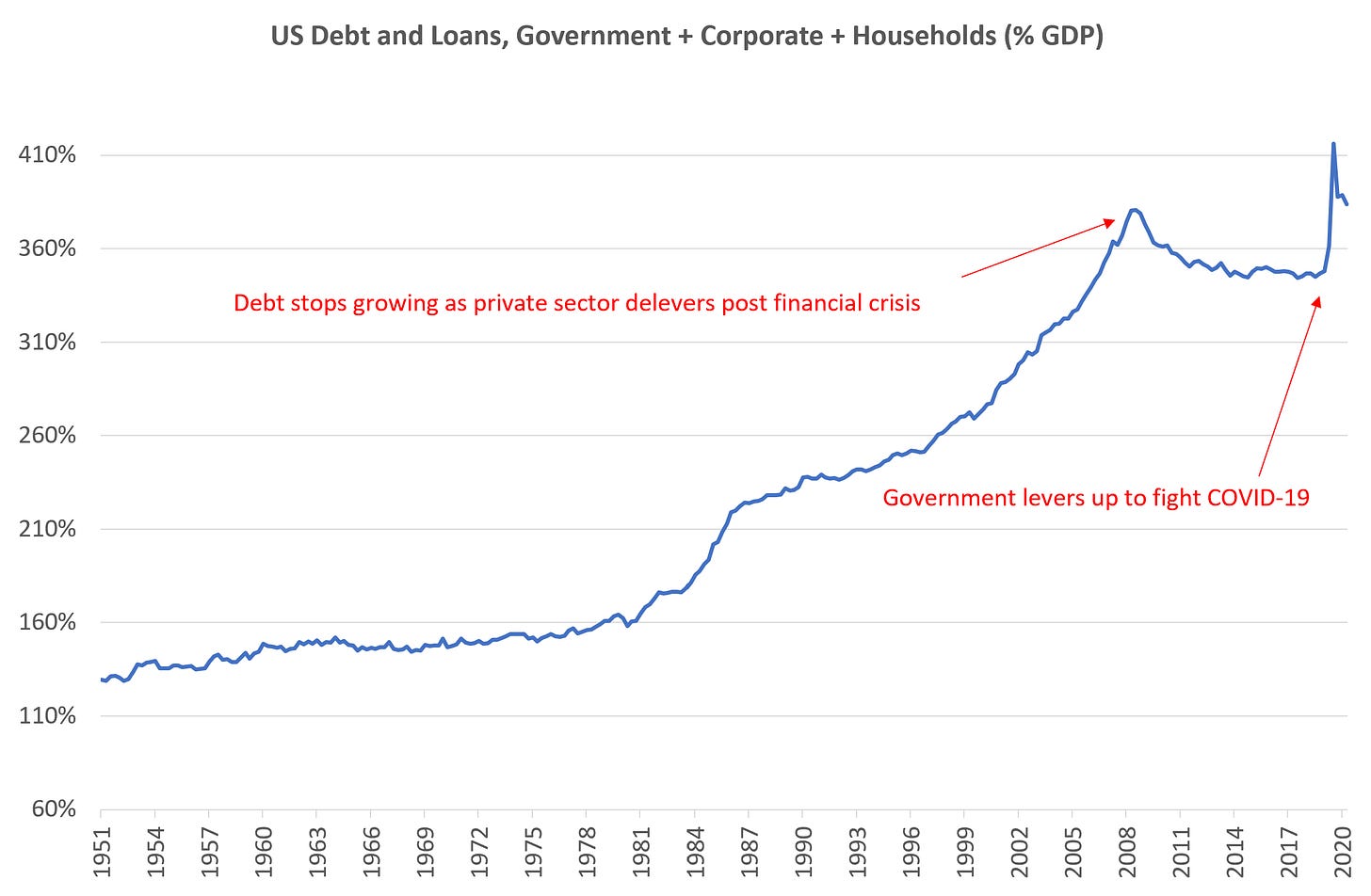

As discussed before, the Western economic system has arrived at a dysfunctional stage, with an exorbitant mountain of debt…

…that requires ultra-low interest rates to prevent collapse

The distortions and inequality created by this setup have become unbearable, providing the incentive for politics to break out of it.1 But how? There are two options:

Default: Writing off debt is a great way to get rid of it. As this would require a complete reset of the financial system (banks holding the debt would go insolvent etc.), it seems an improbable option2

Inflation: When prices increase but the value of debt remains the same, the debt pile shrinks on a relative basis. This route was chosen by the US to get rid of the war debt after WWII

Covid-19 has delivered the pretext to go down the inflation route. With stimulus amounting to ~30% of GDP circulating in the economy, make no mistake, inflation is here. Shortages are the hallmark of inflation, and shortages are everywhere:

There is a shortage of cars

There is a shortage of houses

There is a shortage of workers

There is a shortage of furniture

There is even a shortage of chicken

This goes beyond COVID-19 restrictions, as discussed last week. The President of the Philadelphia Fed, Patrick Harker, summarises it well:

“People are now starting to plan for longer supply chain disruptions than they had initially planned for even six months ago. I just had a meeting with a group of business leaders, and they're clearly seeing that these wage pressures that they're feeling are not going away in the short run, that they're going to have to continue to increase wages.”

And indeed, for the first time since the 1970s (!), wage bargaining power has returned to lower income segments

This is visible in the multiple wage increases this year by Walmart, McDonald’s, Amazon and many employers of low-skilled labor. It also shows in data

For over forty years, politics tried to support a stagnating middle/working class - unsuccessfully. Ever-increasing tensions found an outlet in MAGA, the Gilets Jaunes, or Brexit, culminating with the Man-with-Horns storming the Capitol:

And now, we have finally arrived at a point where the labor market is on fire for low-wage earners

Low-skilled wages are going up - the source of many political tensions has been successfully addressed

This is a major breakthrough. Should it persist, the political implications would be enormous

Take the UK as an example: If the absence of the Polish plumber and the Lithuanian Nanny pushes up wages for the long-struggling domestic low-skilled sector, would anyone want to step in their way and reverse this development?

Does all this come at a cost? Will there be second-order effects down the line? Yes, absolutely

But for now, it’s uniformly welcome. As US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen stated recently:

“We’ve been fighting inflation that’s too low and interest rates that are too low now for a decade, we want them to go back to a normal interest rate environment and if [inflation] helps a little bit to alleviate things then that’s not a bad thing -- that’s a good thing.”

Putting all of this together means we’re facing a political world that likely:

Celebrates the return of wage bargaining power as a substantial success

Will do everything to maintain that state for as long as possible

Will therefore let the economy run hotter for longer, prioritising wage growth over inflation

Accordingly, the odds have risen for structurally higher inflation and with it higher interest rates

An economy with higher growth, higher interest rates and higher inflation would have a very different make-up compared to today’s

Gig-economy business models would face significant pressure from both a cost-of-capital perspective as well as higher labor costs. You may have noticed that Uber-fares have recently gotten uncomfortably higher. Would Uber receive the same funding if it was started next year?

Companies would likely invest more in future growth rather than buybacks etc. Indeed, plans for corporate capital expenditure have gone up considerably over the past few months

Innovation would follow the shape of the economy, potentially pivoting from a focus on cost-savings to more expansive offerings

In terms of investments, what does this mean?

Many financial investor models rely on leverage, low rates and often ever-expanding valuation multiples. There would be pressure on all these parameters, thereby reverting some of the economic financialization of the past decades

For such a context, the best investments are businesses that combine pricing power, exposure to real economic growth and a low valuation

This would favor the inverse of the winners/losers of the past decade

However, financial markets tend to extrapolate recent trends into perpetuity. Relative sector valuations between high-growth tech (disinflation beneficiaries) and commodity producers (economic-growth beneficiaries) are historically wide. What if this reverses?

The current investment world is heavily geared towards the primacy of high-growth tech. Allocations within equity portfolios are at all time highs, so are valuations, funds invested in venture capital etc. Again, what if this reverses?3

The following chart shows the relative valuation of European commodity producers against the broader market:

The investment framework I introduced in previous posts rests on a contrarian perspective. This can be absolute as in the case of Chinese Internet, or relative as is the case here

You can guess from the chart what I’ve been doing in the last weeks - I’ve been buying shares in commodity producers, from copper to LNG and iron ore

In a red-hot inflationary economy, the buck stops with commodity producers. Yet they are on relative historical lows, ignored and under-owned by many

The future is uncertain, and all one can do is assess probabilities. There is a now a case for significant changes in the structure of the economy. If it happens, the impact will be considerable

Are you prepared?

One has to note that there is also the “Japan” Way: Japan has accepted the status quo of exorbitant debt and low rates. It shies away from any big moves to break out from it and as a collectivist society, Japan can cushion the inequality issues via several redistributive channels. For the individualist US, these channels are absent and accordingly the tensions too high to remain in the status quo

In fact, the government debt currently held by central banks might eventually be written off

The counterargument is that we live in an age of exponential technological progress. Keep in mind though that innovation follows economic structure, and much of the new tech of the past decades has been focussed on cost-efficiencies (enterprise software etc.). Equally, prior decades did feature fundamental break-throughs such as air-conditioning or refrigeration. So yes, we live in an age of rapid technological progress, but there have been moments of big innovation before