A Historic Agreement

The US railworker wage settlement points to a stormy period ahead for corporate profits

Last week, following mediation from the US Administration, a new wage agreement was struck between US freight rail companies and unions. It serves as an illustration of the power shift between capital and labor I discussed as early as last October and more recently in “Capital vs Labor, Pt 2”

This post walks through the reasoning, and the profound impacts on corporate profitability, which is under attack from several side. As always, it closes with a perspective of what it means for capital markets, near term and beyond

Let’s dive in. Why do I call this agreement freight rail companies and workers historic? It’s because of the enormous concessions won by the railroad workers. In order to avoid the first strike in 30 years, US freight rail companies agreed to these terms:

A 24% wage increase by 2024

A 13.5% wage increase, from today

A $1000 annual bonus per worker for the next five years

Improvements to healthcare coverage, in particular the right to take unpaid leave off to attend medical appointments

Freight railroads are a neuralgic industry

If rail workers strike, not only the rail companies suffer, but the entire country. About $2bn worth of goods are shipped everyday. In theory, this gives much leverage to the rail workers’ unions

Indeed, historically, rail strikes were frequent. Yet, there hasn’t been a strike since 1992. Why?

It’s a long and short story. Stay with me. First, this happened:

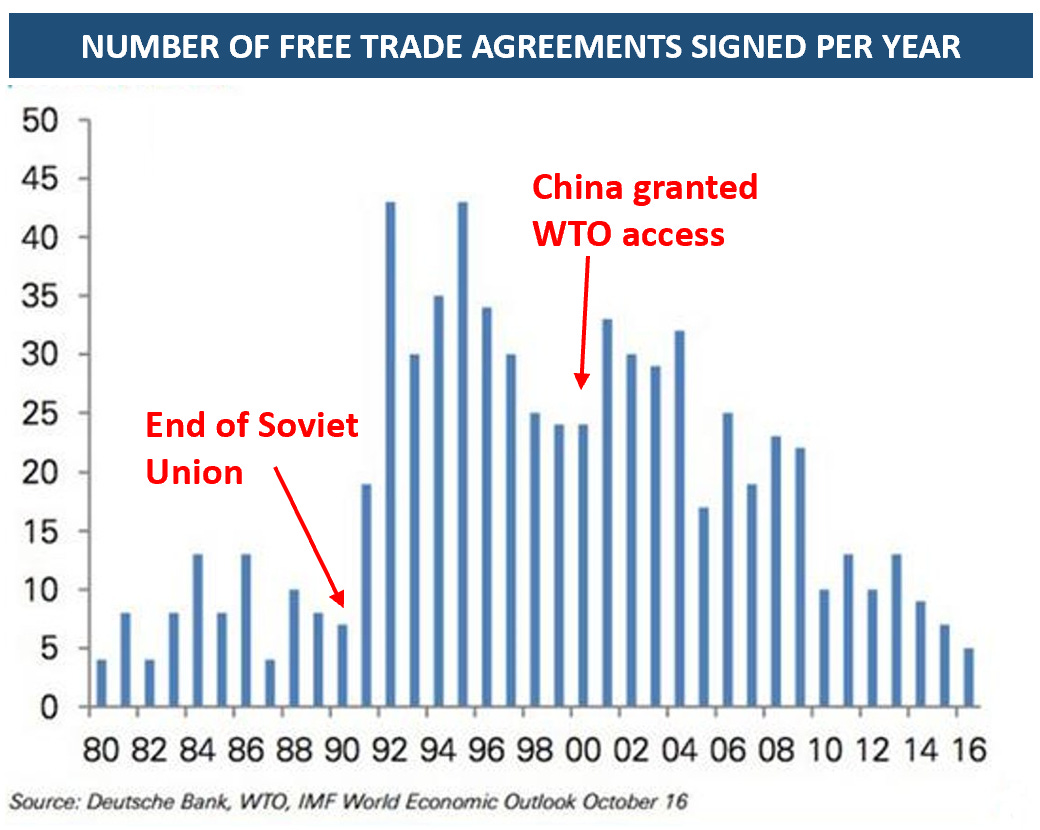

In 1989, the Iron Curtain fell

In its wake, globalisation took off, and a flurry of trade deals opened the world’s labor markets to Western companies, culminating in China’s accession to the WTO in 2000 under Bill Clinton

Globalisation was a gift to the world. An estimated two billion people were lifted out of poverty in emerging markets. However, there was also one big loser - the Western middle class

US and Western European companies outsourced production to China, South-East Asia or Eastern Europe, which offered cheap labor and low regulation. Accordingly, they needed fewer workers at home

This broke domestic labor bargaining power. With no leverage, trade unions had little to offer and their influence shrunk. Membership of UK trade unions halved between 1980 and 2020, as did the share of union workers in the US

You might ask, how did that affect US rail workers? An illustrative example: General Motors outsources a plant to China → The GM worker loses his/her job → joins growing pool of blue-collar unemployed → more competition for freight rail jobs

For the best part of the past two decades, there was much slack in the US labor market

The chart below shows the - currently much discussed - ratio of unemployed vs vacancies since 2000. The large orange area represents the overhang of job seekers, at times there were 5 unemployed for 1 open position

This dynamic is very visible in the freight rail companies’ Profit & Loss statements. Without leverage, unions stayed timid. Labor costs, which are ~40% of RailCo expenses1, remained in check. The result was a stunning:

The below chart shows the EBIT-Margin of CSX Corp, one of the Freight RailCos, since 1990. It quadrupled from 10% to 40%. Yet the business is the same today as in 1990. Putting goods into carriages, and moving them from A to B

Globalisation’s effect on the balance between capital and labor went beyond anaemic Western wage growth

Low wage growth meant low inflation. Because of this, the Fed could stimulate economic growth by cutting interest rates and conducting QE, which provided the world with $8 trillion balance sheet capacity to lever up

Low interest rates and the resulting high asset prices incentivised the use of buybacks and dividends to drive shareholder return over Capex and R&D

Executives are typically paid on earnings per share, and paid with share grants. Earnings per share are increased by buybacks, with cheap leverage providing the capacity to do so. Low interest rates drove up equity valuations, increasing the value of share-based compensation

This effect is visible when assessing the use of corporate cash over time. Buybacks and dividends have increased by 2.5x since 1980, at the expense of capex and R&D

So how could rail workers suddenly reach such a favourable deal for themselves, after decades of restraint?

The answer is simple. As we all know, today’s labor market is extremely tight. The ratio of job vacancies to unemployed (see above) is at a historical high. Negotiating leverage is back, and the unions used it, with plenty of political backing

Political backing wasn’t always there. Strikes in critical industries are a huge nuisance for everyone uninvolved. In the 1980s, both Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher took a heavy hand to break them

When air traffic controllers went on strike in 1981, Ronald Reagan ordered them by executive degree to return to work. Anyone who didn’t was fired on the spot - almost 12,000 controllers lost their jobs. More so, Reagan declared a rehiring ban to the FAA for all those fired

In 1984 and 1985, Margaret Thatcher fought the English coal miners’ strike that threatened to cripple the UK’s energy supplies. Her unyielding stance involving heavy police action against picketers eventually ended the strike, which was dubbed the most bitter industrial dispute in British history

Can we expect similar political intervention today, should strikes in critical industries get out of hand? Unlikely, I believe

Reagan and Thatcher had the public’s backing, which after a “decade of discontent” was tired of strikes and disruption. Today, we are only at the beginning of this shift in power, and public discontent still sits against globalisation and corporates

Summary: Exceptionally tight labor markets shift power back to labor and away from capital, with the freight rail agreement a testament to this dynamic. Political support remains favourable, and high corporate margins provide ample capacity for a growing labor share

Now, let’s connect the rail settlement more broadly to corporate profitability. I continue to maintain the following assumption:

Why is that?

We know that corporate profitability is under attack. There has been a plethora of profit warnings recently, from Fedex to Ford or Dow Chemical. In spite of this, labor market dynamics continue to evolve very differently

Unemployment usually rises materially towards the end of an economic downturn. But leading employment indicators can provide a window into future trends. One of them is weekly initial claims, which people file who have just been laid off

After a small bump, this number is trending down again. More so, while the chart below shows the seasonally adjusted number, the unadjusted number was the lowest in 53 years (!)

Now, in order to fight inflation, the Fed is trying to slow the economy by raising interest rates. In more candid terms, it attempts to create unemployment to break the spiral of higher wages begetting higher inflation in an overheated economy. But here is the issue

We know from the earlier chart that there are currently ~11m vacancies and ~6m unemployed, a ratio of ~1.8 (vs historically <0.7)

Just to bring this ratio back to 1, which would still be a historically tight labor market, 5 million job opening would have to be “destroyed”, almost twice as many as during the Great Financial Crisis!

A monstrous recession is likely required to achieve this reduction of job openings, just to bring the labor market from “super-tight” to “tight”.

It seems unrealistic to me that this is either possible or desirable - how high would interest rates have to go, how much collateral damage would that cause?

Meanwhile, in my view, many miss the US consumers’ resilience against higher interest rates. Why is that?

The US consumer continues to sit on high cash balances, as frequently discussed before. These now also provide an income as they pay interest again, as long as consumers allocate them to money market funds or T-Bills

Household leverage largely comprises of mortgages. These are typically fixed rate, 30-Year duration and have mostly been refinanced at rock-bottom rates. Higher interest rates have no effect here

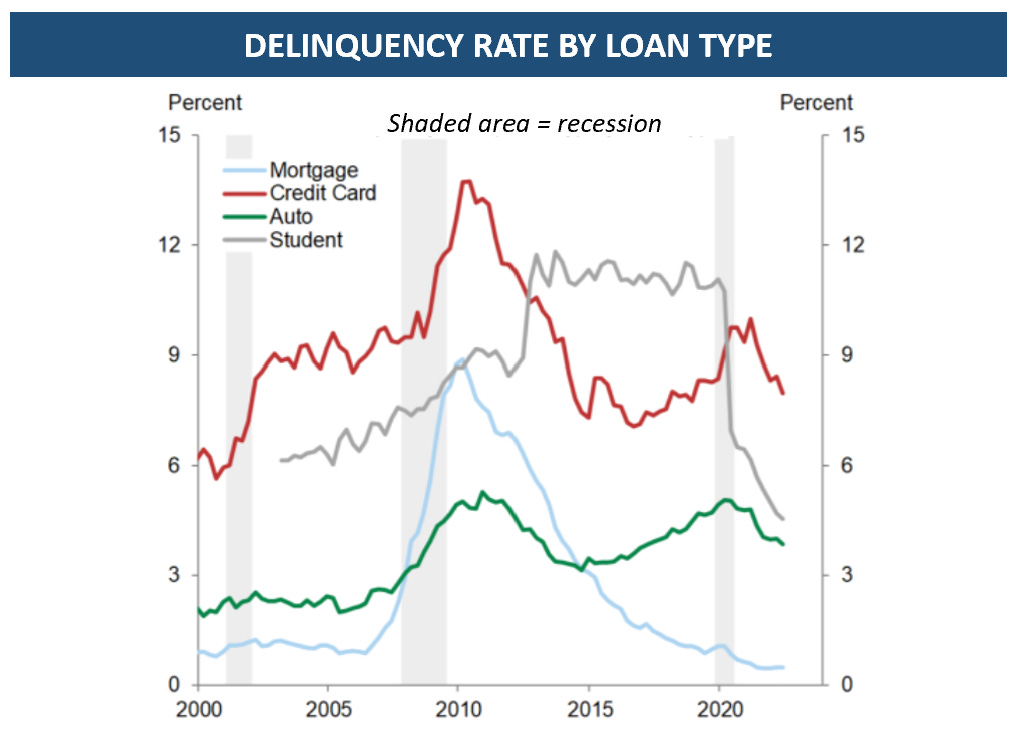

Credit card and auto loan rates have gone up a lot, but are a small share of consumer debt and credit card debt especially was already very expensive

As higher interest rates drive down commodity prices (e.g. gasoline), they free up consumer income that can be spent elsewhere

As a result, despite the rapid increase in interest rates, with the 1-Year T-Bill now paying 4%, consumer loan delinquencies still trend down and remain near historic lows

Higher interest rates only have a limited effect on consumer demand. But they do have a massive effect on corporates. In fact, we likely witness the reverse effects of the past decades

Higher rates increase the cost of capital for corporates, leverage becomes more expensive

This likely leads to a re-prioritisation of corporate use of cash. If consumer demand remains - through the cycle - healthy, capex will be prioritised to cater to future demand (if you don’t invest, your competition takes the future customer)

As overall leverage gets more expensive, buybacks and dividends will be deprioritised. In other words, this chart unwinds, with the corresponding impact on corporate profitability

However, the onslaught on corporate profitability does not end here

For obvious reasons, higher interest rates mean higher corporate interest expense

Corporate taxes are in a multi-decade downtrend. This may change as a slowing economy balloons already high government deficits. The Netherlands just increased corporation tax from 15% to 19%. In the same legal act, it also increased the minimum wage by 10% - a sign of the times

Lower interest rates and lower corporate taxes provided huge tailwinds to corporate margins over the past two decades, as the chart below shows - this likely reverses now

Finally, commodities are tied to the economic cycle which is now in a downtrend. However, they remain elevated in historic comparison, and any incremental central bank liquidity provision would make them rally again. Expect corporate cost pressures from commodities to remain high, cf. Ford’s profit warning on higher supplier cost

Conclusion: Corporate profitability faces unprecedented headwinds from higher labor costs, higher interest expenses, higher taxes and higher commodity costs. The flipside of this dynamic is likely a higher relative share of the economic pie allocated to “Labor”, after a four-decade trend in favor of “Capital”

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

Cash - Regular readers will be familiar with my view, since the beginning of the year, that for anyone not wanting to trade or short, cash would be best in an asset price deflation scenario. Now that cash can be safely put to work, as the 1-Year US Treasury Bill has passed 4% yield. This is a decent return, while dynamics for most other assets remain negative. I find this very compelling. As the economic slowdown intensifies, to likely peak in mid/late 2023, credit spreads likely widen. Then, funds can be rotated out of T-Bills into corporate and distressed credit

Equities - Earnings estimates are too high, equities are too expensive vs bonds and liquidity is withdrawn at a record pace. I could not make up a more bearish picture for this asset class. One-sided positioning is the only bright spot, but it is not extreme enough to produce more than limited counter-trend rallies, in my view. I remain short

Europe - I continue to maintain that financial markets underestimate the impact of the European energy crisis on corporate profitability

German producer price inflation yesterday came in at a shocking +7.9% m-o-m vs 2.4% estimated, and +45.8% y-o-y. This puts German businesses on a different trajectory vs. their US, Chinese or Japanese peers and represents a huge competitive challenge

Please keep in mind - this spike is largely driven by higher gas prices, which have since declined (see chart below). However, the pressure on producer prices is likely to remain, as many companies hedge their equity exposure and thus the higher energy costs only hit once the hedges roll off. This explains why the monthly PPI did not turn negative after previous gas price declines

I remain short DAX and European Industrials (SXNP) as well as short Schatz futures (2-Year German debt), please see previous posts for more details. However, I do want to highlight a silver lining: European companies will go through tremendous efficiency efforts (though unlikely at the expense of labor given the skilled worker shortage), and gas is ubiquitous, it will eventually be cheap from other sources. As such, some European businesses will likely be in great shape 2-3 years from now. They adapt to tough times, and then times get better

UK - The UK remains a startling case, with new PM Liz Truss engaging in “Voodoo-economics” as debt-financed tax cuts and subsidies provide newly printed money into a highly inflationary economy. In my view, it remains a fallacy to think the tax cuts would stimulate business investment, as they are “paid for” by a weaker Pound, higher inflation and higher volatility, all of which deters investments. The latest experiment in “Voodoo-economics”, i.e. defying economic laws of gravity, was provided by Turkey’s Erdogan, and it did not end well. Also notable - yesterday Liverpool’s dockworkers rejected an 8.3% pay rise and £750 one-off payments and began a two-week strike

Bonds - I had written about the triple dynamics of lower foreign US Treasury demand and lower Fed participation via QT and higher fiscal deficits before here and here, and accordingly concluded that the high in US long-term bond yields would not be in. This has turned out to be accurate, as the 10-Year followed the 30-Year to a new high yesterday. A pause may be warranted here, but bond yields likely have further to go as long as these dynamics persist. In turn, this will likely weigh on all risk assets. I see the Fed as global buyer of last resort that eventually steps in, as market tremors escalate and the paradox of either defeating inflation or saving the government debt pile is laid bare. This moment does not appear to be close

I would like to conclude with a medium term outlook. At this stage, I need to emphasise that the future remains highly uncertain, and the range of outcomes is very wide

Having said that, I see a high likelihood for a prolonged inflationary bear market. In my view, very few investors are positioned for this. Many portfolios resemble what is shown below, the asset allocation for US endowments

In other words, a substantial overweight in levered equities (PE) and long-duration equities (VC), and a dramatic underweight in real assets and fixed income

Should an extended inflationary bear market materialise, some of the biggest winners are likely to be banks (as interest rates rise, especially in Europe, every 1% increase in rates = ~20% more revenues) and commodities (as the money supply grows). In other words, the most hated, under-owned sectors of the past decade. I deliberately excluded real estate, as in many countries a massive housing bubble was blown (e.g. US, Canada, Germany), driven by 0% or negative interest rates. In contrast to the 2010s preference for secular growth companies, banks and commodities are highly cyclical areas, which creates unfamiliar challenges in owning them at the right time of the cycle

Now, both the PE and VC industry will adjust to a new paradigm, should it occur. I would expect savvy PE firms to quickly integrate the different context into their buyout strategy. Equally, there seems plenty opportunity for VCs where high-growth and an inflationary world intertwine, e.g. energy efficiency or alternative energy sources

Finally, I also cannot rule out a return to secular stagnation and the challenge of absorbing excess savings, as Larry Summers recently highlighted in a speech at the Cato institute. I personally see inflation mostly tied to the labor market, which in the future likely remains much tighter in light of deglobalisation (e.g see here on EU companies retreating in China), the demographic cliff and lower immigration, but this view might be wrong

Whatever the outcome, it seems highly likely that the “autopilot” setting of the past decade, i.e. buy high-beta assets and go to the beach, is over, followed by a much more volatile period requiring a different skillset

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!

Excluding depreciation

It is an interesting flywheel.

Geopolitical/supply chain shock -> higher cost of base goods -> gov/corps supporting consumer balance sheets -> weakening gov/corp profitability -> higher yields -> attract funding for capex directed at solving expensive commodity/supply chain costs -> hopefully back to a less inflationary world with structurally lower commodity input costs. Yes, overwhelming majority of SP500 won't like these dynamics. Question is how does the consumer end up? Can they extract enough wages from shareholders? It will be a battle and I suspect real income and living standards for all will suffer/be more expensive.

Where is growth? Probably in businesses trying to solve for the geopolitical/supply chain shocked world. Something tells me demand reduction induced by CB won't be enough to solve for higher prices without a serious employment crisis (as you alluded to). Worried about credit cracking in the meantime! Consumers are starting to feel the pinch.

Surprised an OPIC hasn't formed to counter OPEC. Though I suppose the G7 price cap might be the first hint of that.