Capital vs Labor (Pt. 2)

Why a profit recession is much more likely than an employment recession

The economic process requires two ingredients: Capital to acquire supplies, and Labor to turn them into a product. Capital is rewarded with ownership, Labor is rewarded with wages. They are united in their goal of economic progress, but in competition over its rewards. As with many things in life, the perfect state between the two is a balanced equilibrium. However, historically, this has hardly been the case

In the 1960s and 1970s Labor was too powerful. Strikes, overregulation and inflation brought winters of discontent. Out of balance, the pendulum started to swing the other way. Paul Volcker, Milton Friedman, Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher are synonymous for initiating a turn that lasted four decades. They were helped by North Sea oil that broke Middle Eastern resources dominance, and globalisation which added millions of cheap workers to the global labor pool

Growing up in Germany in the late 1990s/early 2000s, every other day I read headlines of plant closures to be moved abroad, such as the Bochum Nokia plant, which was once Europe’s largest TV producer. The dominance of Capital and its deflationary dynamics became a hallmark of mine and the following generation

However, in the late 2010s the pendulum had once again swung too far. Negative interest rates assigned an extraordinary share of the economy to asset owners, unions were powerless sideshows, unemployment was high and trade barriers removed such as Clinton’s 2000 China WTO accession. Western inequality rose and eventually political discontent went through the roof. A turn was on the cards, first initiated by Trump as agent of deglobalisation, soon after followed by trillions of COVID-19 bailouts

Last October, I wrote a post called “Capital vs Labor” that predicted this shift in power. Ten months later, it is time to revisit the case and look for evidence in recent data

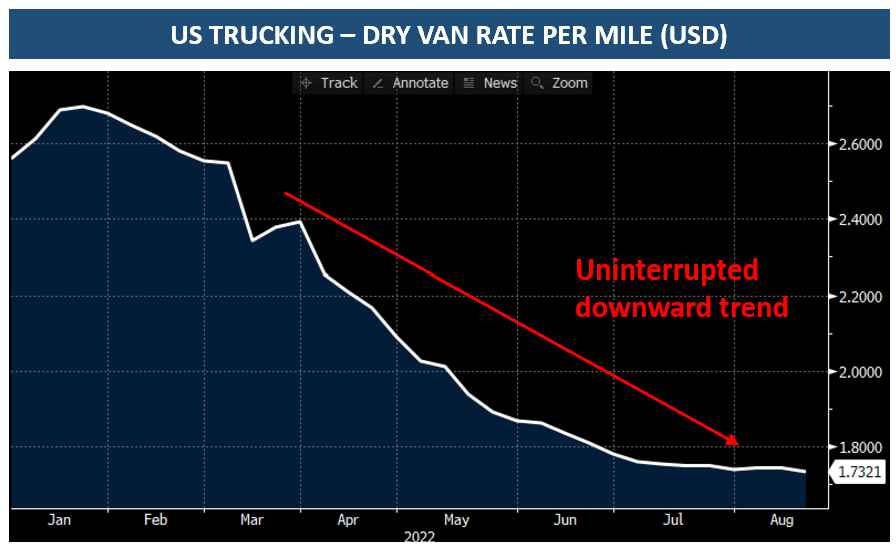

As you know, rather than being bullish or bearish, my approach is data-dependent, and I track hundreds of datapoints to judge how the economy and markets evolve, from Rolex prices to US visa applications or Trucking rates. I share much of this freely on Twitter

As usual, this post closes with an outlook on markets, where I explain why I added to a recently initiated long Oil position

So, on the topic of Capital vs Labor, what does the data tell us? Let’s start with Labor, represented for our purposes by the US consumer

We know the US consumer has been squeezed by inflation. In response they cut back, and as a result demand-sensitive goods such as gasoline declined in price. In turn, this boosted consumers’ real income, which in July printed markedly positive

Now, with better real income, we’d expect an improvement in consumption. Let’s have a look whether some near-time datapoints confirm this:

Earnings updates from US retailers such as Walmart, Home Depot or Target, many of which include July in their most recent quarterly data, have been tracking better than expected

July retail sales came in stronger than expected, with +0.4% (excl. auto) vs -0.1% expected

Looking at the first available August data, Credit card spend accelerated visibly early in the month

Further confirmed by withheld payroll data by the US Treasury, which I introduced in a recent post as (albeit noisy) near-term indicator. It also accelerated in early August

The answer is yes - the relief from lower gasoline prices immediately translated into higher spending. This suggests the US consumer is generally in decent shape, as it quickly responds to lower prices. This decent shape is also reflected in credit data:

Delinquency rates, whether for credit cards (pictured below), student debt or mortgages, all track at historically low levels

Consumer cash balances remain high. Only the lowest income quintile has used up all stay-at-home savings and stimulus cheque money. While this is socially very concerning, this group contributes <10% to consumption

Summary: Looking at the consumer as a proxy for Labor, things seem to be in decent shape

Savings are high, delinquencies low, unemployment very low and consumption has just been boosted by ebbing inflation

Let’s now turn to Capital, this time using industrial data as a proxy. And here, things look much worse:

I could pick many surveys, below data from the Empire Manufacturing Survey is just one example. General business conditions are assessed to be exceptionally poor by respondents

It is not only manufacturing businesses. Take Homebuilders as another example, their assessment of the state of the world is similarly despondent

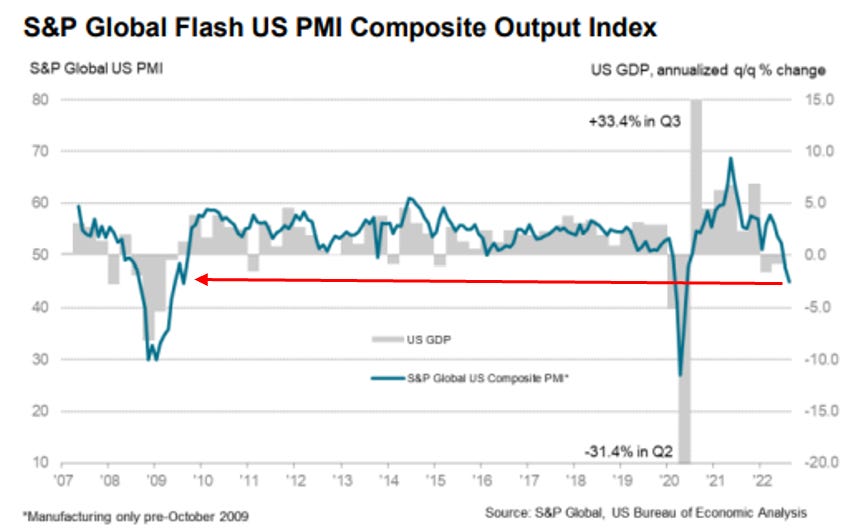

Today’s S&P US Flash PMI survey, which includes both manufacturing and services businesses, came in very weak

The survey mood is also reflected in hard data. Using US trucking rates as a proxy for industrial activity, they have been dropping all year

Summary: Industry surveys and data paint a dark picture, commensurate with a severe recession

What’s going on, how do we reconcile the two? Is it just a lag, or is there more going on? The answer has to do with inflation and inventory

First, high inflation changed the composition of consumer expenditure. More is spent on necessities like food and less on discretionary items

Second, retailers stocked items that match past consumption patterns. So their inventories ballooned, they own the “wrong” stuff

What do retailers do with too high inventories? They cancel supplier orders until the inventory is worked off:

And this is where the disconnect originates. If Walmart cancels orders, this feeds through the entire value chain, from the wholesaler to the producer to the commodity mine. In other words, one giant inventory whiplash

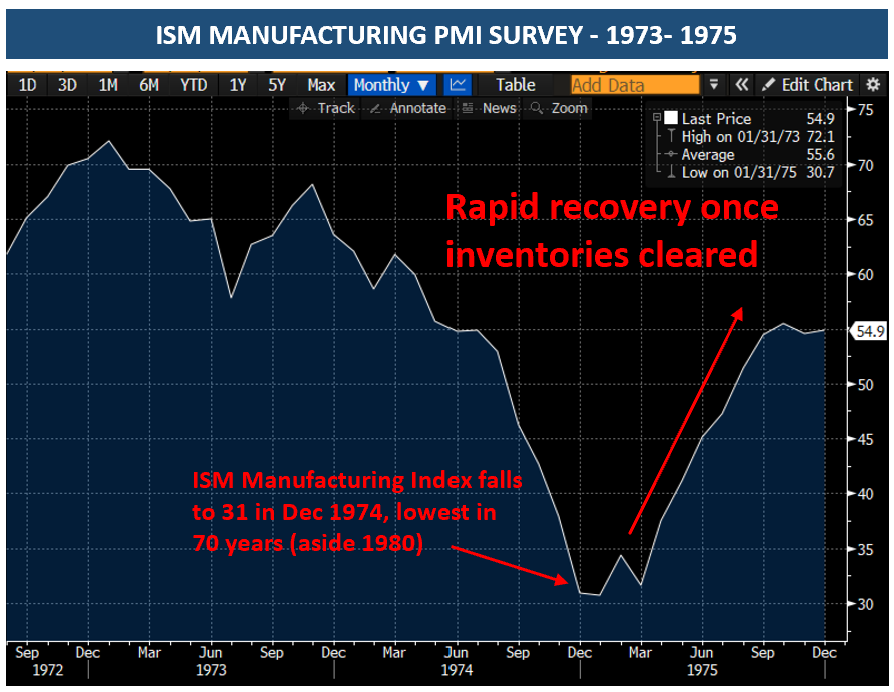

We have a historic parallel. In inflation-ravaged 1974, the ISM Manufacturing survey fell to an multi-decade low of 31. In the same year, nominal GDP declined by only 0.4%

Judging from this, once the inventory clears, industrial mood should somewhat brighten - but do we have any data to assess that already?

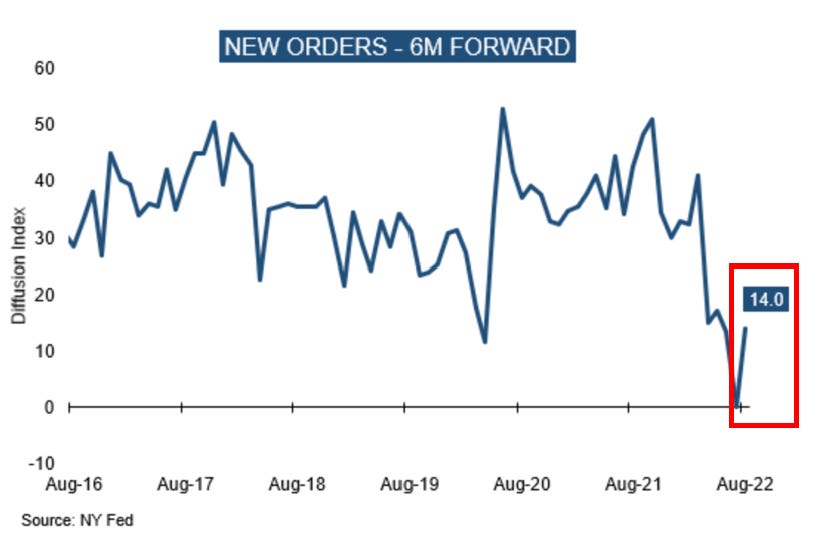

We do - the regional Fed surveys ask businesses also about their view of the world six months from now - the other side of the inventory bullwhip

And what do we see there? A notable uptick in new orders from apocalyptic levels

More so, we also get an idea what that might mean for inflation - is the current ebbing transitory or will goods inflation return?

With an improvement in this new orders outlook, “prices paid” in six months also ticked up, from a still elevated level. This suggests inflation will come back as orders return

Similarly, we see an improvement in number of employees six months form now, relevant for wage inflation

Summary: Businesses face an intense inventory whiplash. This overstates the decline in end-demand, but it is very painful for corporate profits

Now, inventory dynamics might cause a short-term divergence in the fate of Capital vs Labor. Beyond the short-term, the evolution of the labor market is key

The above survey datapoint already gave a hint, but let’s expand on it for a moment. There are three huge tailwinds for tight labor markets that might lead to a very different evolution of unemployment during the coming economic slowdown (yes, there will still be a slowdown)

First, the demographic cliff

Over the coming decade, millions of boomers are bound to retire. They will be missed in the labor market, but they continue to consume

We witnessed a preview over COVID-19, when many >55 year olds retired early. This contributed materially to the current record low unemployment1

Second, deglobalisation

The schism between China and the US triggered a reshoring wave, with 350k jobs “brought home” in 2022, despite higher costs. This trend is in its early innings, amidst geopolitical tensions around Taiwan and joint Russian-Chinese military exercises

Third, immigration

Trump and COVID-19 slammed the breaks on US immigration, and the Biden administration has so far done little to reverse it. Europe put up fences on its borders and the UK sends refugees to Ruanda for “processing”. It is fair to say that the political climate on immigration has changed

The demographic cliff, deglobalisation and lower immigration all signify a much tighter future labor market. What do we see in response? Unions are making a comeback

The erosion of unions in the 1990s and early 2000s was unsurprising. They were powerless against the forces of globalisation, so what was the point in joining them?

With a changed labor market, the role of unions is redefined. Amazon, British Airways, Uber, Apple, or British ports are all examples where unions recently achieved substantial pay rises or otherwise gained a foothold

What does that mean for companies? Simple: More, continuous cost inflation

While cost pressures from commodities have (temporarily) abated, companies reporting higher input costs due to higher wages hit another record high2

Walmart’s CEO Doug McMillion summarises with some hyperbole:

Conclusion: After four decades of Capital in the driver’s seat, the balance of power is shifting back to Labor. A cash-rich US consumer is resilient against economic shocks, and the demographic cliff, deglobalisation and lower immigration provide for a tight labor market and likely only a limited rise in unemployment

So something else will have to give. That something is corporate profits. These will likely be squeezed between a slowing topline and a growing cost base

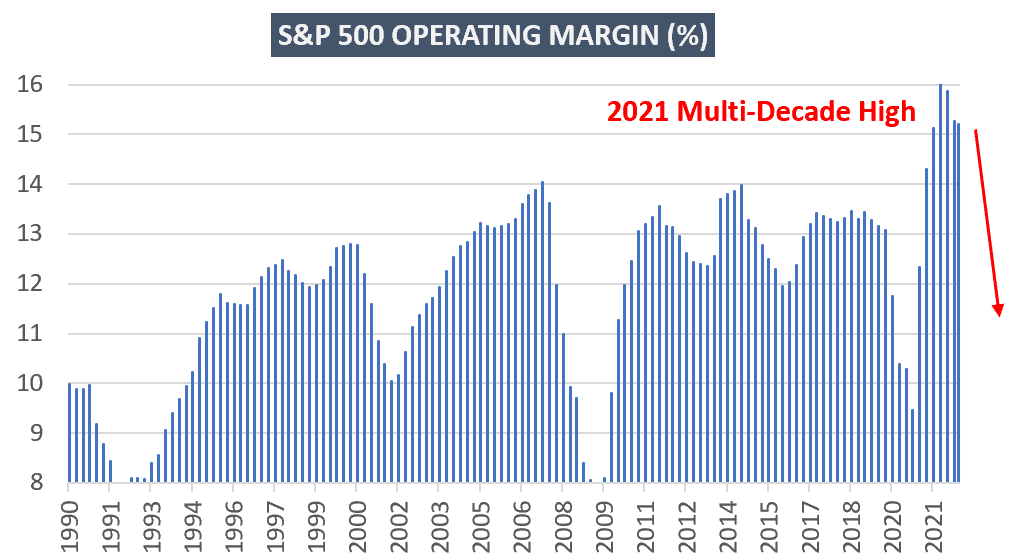

NB: Corporate profit margins shot to all-time highs during COVID-19. There is ample space for mean reversion

Add to that likely higher medium-term bond yields, and the outlook for equities certainly looks difficult

My base case for the US remains a prolonged period of poor real GDP growth, an industrial recession, moderate unemployment and lingering inflation. This would translate into a declining stock market, interrupted by violent bear market rallies, that might durably turn upwards ~mid 2023, 1-2 quarters before the economy turns

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting the dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

Equities - As discussed in recent posts, I have layered shorts into the recent market rally, which has now turned down. Higher equity prices appear unsustainable in light of the likely EPS erosion discussed in this post, as well as rising bond yields (more below). Signs of froth also re-emerged. I remain short, in particular Nasdaq-100, US Airlines (JETS), Russell 2000 (IWM), Semiconductors (SMH), German equities (DAX) and European Banks (SX7P). With regards to the Nasdaq-100, I want to highlight the below comparison on Apple, which - in my view - remains a consumer discretionary company, with 21% sales in Europe and 18% in China. Its stock has run back up near all-time highs:

Further, I’ve once again entered a short in Homebuilders (XHB), discussed here, which has diverged from bond yields, via mortgages the main driver for Housing. I continue to believe there to be significant downside to house prices, in particular in Canada and Germany, but also in the US

Oil - I highlighted this as a new long position in my last post, as proxy for an resurgence of inflationary pressures and amidst excessively negative sentiment. I have since added to it, also in light of Saudi comments yesterday which suggest OPEC+ production may be curtailed if prices decline further. Keep in mind, the SPR release is scheduled to expire after the midterms. Incremental demand from Europe’s gas crunch also seems likely, see the Swiss government advising Zurich Airport to switch heating from gas to oil

Commodities - Please see my recent post for a more detailed discussion. Today I want to highlight US natural gas futures, which continue to climb, and in my view likely have further upside once Freeport LNG reopens in early October and exports to Europe are possible again. US Henry Hub is a proxy for US power prices, and for obvious reasons important for the inflation outlook

Bonds - As discussed, it is evident that inflation hit a soft patch over the summer, further confirmed by a 3.4% decline in the Manheim used car index for early August. I feel that the Bond market debate has moved on, with 10-year and 30-year yields rising despite a sharp decline in 1-Year inflation expectations. The bond market now likely focusses on the medium term outlook for inflation, as well as the financeability of the US Treasury deficit - either give reason for higher yields going forward, as would higher oil prices

Europe - It is hard to not sound dramatic when assessing Europe and the UK’s situation, but the situation could hardly be more serious. Any activity requires energy, and the European cost of energy has gone up >10x, if measured by 1-Year forward power prices. UK and Eurozone inflation will likely hit mid/high teens while economic activity is severely curtailed. Wage demands will likely come in much higher, fuelling a price-wage spiral while unemployment stays low. ECB interest rates remain comically low. I am short Schatz futures (2-Year German government bonds)

Crypto - Bitcoin is a proxy for central bank liquidity. For now, the Fed as well as the ECB continue to tighten liquidity (maybe insufficiently so), but one day they will loosen the screws again. Whether that day is in three weeks, three months, or three years I do not know, but until then the environment remains challenging for crypto

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!

Keep in mind that older employees have high skills acquired over decades of practise. This issue is particularly pronounced in Germany, where we see a record shortage of skilled workers, despite the economic turbulence

There is a noticeable divergence between blue-collar and white-collar jobs, with the former suffering from shortage and the latter with some overbuilt. See Ford’s recent announcement to cut 3000 workers, all white-collar