Food = Energy

The focal point of Europe's crisis. Plus: What Ukraine's recent military success could mean, and why I flipped short-term bullish

Two weeks ago I wrote about a post about Europe’s energy crisis, and the severe consequences in case no action was taken. Much happened since: Germany announced a €65bn support package for households, the UK’s new PM Liz Truss went to cap individual energy bills at £2500 p.a. for two years at a cost of £120bn, a Europe-wide electricity price cap of 200 €/MWh is in the making and Norway is open to reducing the price at which it sells gas to Europe

All measures have in common that they reshuffle the monetary impact to a fairer distribution. This likely reduces scarring and insolvency cascades. However, a shortage of energy remains, and that expresses itself most urgently in food

Food and energy are intimately related. We consume food, which gives us energy to move and think. Food in turn requires energy to grow and be prepared, from gas-intensive fertilizer to power-intensive processing plants

This post looks at the energy deficit’s impact on our most primordial sector, to also briefly expand on recent Ukrainian military success. As always, it closes with a current outlook on markets, where I lay out why I have covered shorts and flipped short-term bullish, with US high-growth tech as fastest horse

To start, let’s briefly recall what is a the heart of Europe’s issues

Russia halted most gas flows to Europe, which are needed for (1) power generation, (2) domestic heating and (3) industrial production

Thus, Europe is now short of energy. The effects vary from country to country. Germany sits near the European median, with 27% of primary energy covered by gas, and half that provided by Russia. Most of it goes to domestic heating and industry…

… elsewhere, in Italy, power generation is very vulnerable, with over 50% provided by gas power plants

As a consequence of the shortage, we now see a slowdown in European industrial production. This is likely in its first innings, to extend well into 2023

European industrial production turned negative in August in Germany (-0.3% vs 0.8% July), France (-1.6% vs +1.2%), Ireland (-18.9% vs. +11.3%), Austria (-3.9% vs -0.8%) and the UK (-0.3% vs +0.3%)

In terms of exposed industries, many sectors are heavily impacted, from aluminium to steel or paper. One sector stands out though - fertilizers

Why? Ammonia, with 60% the biggest fertilizer group, is created by mixing nitrogen from the air with hydrogen from natural gas. No natural gas, no ammonia

With gas either unavailable or prohibitively expensive, many European fertilizer plants have shut down in recent weeks

The very first level of the food value chain, the growing of plants, is massively impacted by this. 50% of the world’s food production depends on ammonia

Keep in mind: Europe’s shortfall can be covered by foreign imports. But these are (1) much more costly and (2) the ammonia is redirected from Emerging Markets, leading to food shortages there

Moving on to the next stage of the production process, power costs are problematic

Food production is energy-intensive. Just think about your local bakery’s big oven that bakes bread at 250 degrees Celsius

Speaking of Bakeries, in a now already notorious TV-interview, German economic minister Robert Habeck acknowledged their cost pressures and suggested they could just “shut down for a few months”. He course-corrected the next day, promising more help for SMEs

Food producers Suedzucker, Tate & Lyle and Allied Bakeries all reported substantial rises in energy and packaging costs

Food is an essential good, we cannot live without it. As such, food producers have high pricing power, so they pass on these cost increases to consumers

See what Unilever’s CEO had to say last week:

In other words, global food inflation is still on a very different trajectory than say inflation in cars, airfares or freight rates, which we know is trending down

Unsurprisingly, looking at the IFO survey for business price increase plans, a stunning 99% of German food businesses plan to increase prices over the next year

Summary: The surge in energy prices likely drives European food prices significantly higher, well into 2023

This is politically toxic. With food inflation, nothing can be done to avoid it. This is very different to discretionary items. It is also more essential than gasoline. One can always drive “a bit less”, but hardly eat “a bit less”

Consumers will be hurt badly. They will ask for higher wages, and as the demographic cliff tightens the labor market, e.g. with a record shortage of skilled workers in spite of economic turbulence, they have the leverage to achieve them

This implies a price-wage spiral, which would add to European inflation that is already fuelled by deficit spending. The ECB is rightly worried about these dynamics, its board member Klaas Knot last week made the strongest statement yet against these “second order effects”

So what could be done? As I mentioned at the outset of this post, food is energy, and Europe is short energy. Further, on a long enough timeline, all energy is interchangeable

As an example, if the price of gas is high, this incentivises oil to be burned for power generation, so oil expands its role from transport to power

With this in mind, the shutdown of Germany’s nuclear capacity when any source of energy is needed just looks like the wrong move

To be clear - I get the aversion to nuclear. I grew up with the Chernobyl catastrophe, and remember when we kids were told not go to playgrounds because the sand would be tainted, and months of salad and mushroom harvest had to be thrown away

But Germany’s plants are state-of-the-art, another few years don’t change the equation and Germany now instead fires up coal power plants. Their share in Germany’s power mix 2022 has grown to 32% from 27% in 2021 (Nuclear 6% from 12%) and they produce ~1t of CO2/MWH (vs Nuclear near 0). On that note - If you believe in climate change (I do), Germany seems heavily affected, with zero days above 40 degrees in 1982 and more than twenty in 2019

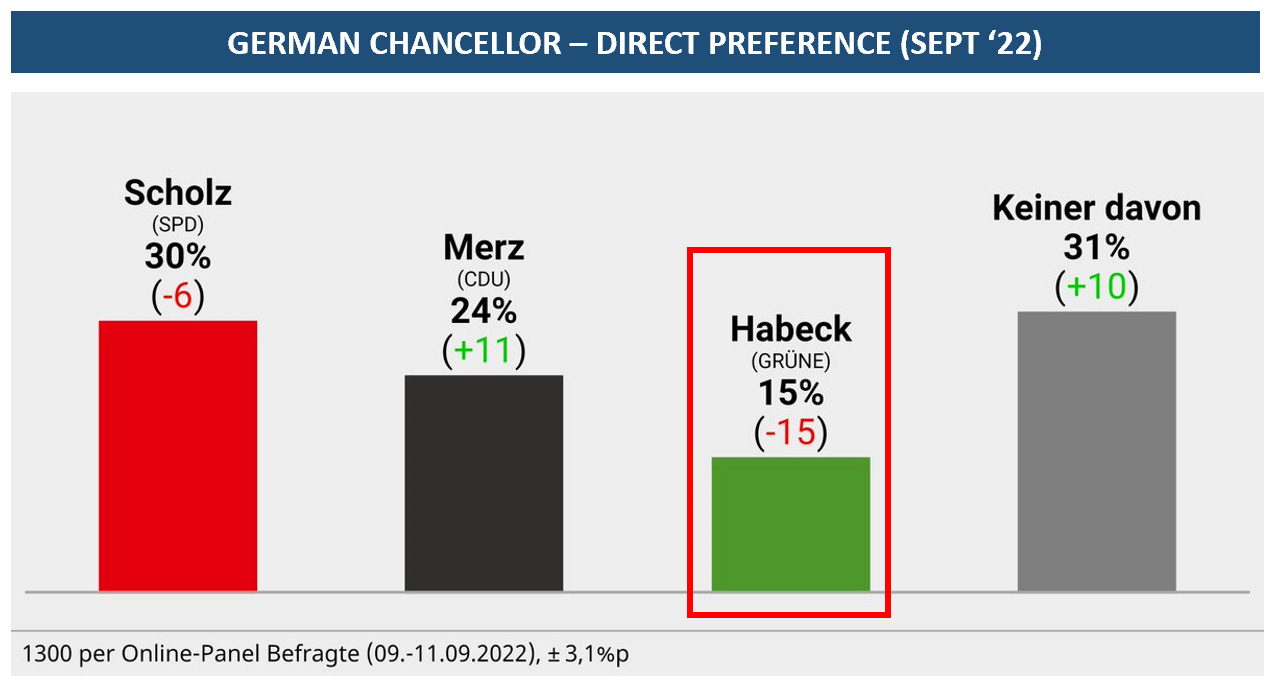

It seems to me that politics is mostly about common sense, and this common sense is missing in Robert Habeck’s decision to put the remaining nuclear plants only in reserve (rather than producing) and only until April 2023. The German public agrees, as recent polling suggests:

Summary: Europe needs all the energy it can get, including Germany’s nuclear plants, even if they run only for a limited period longer

Meanwhile, over the past week, the Ukrainian army made astonishing advancements, recapturing an area as large as Cyprus, Delaware of the Ruhr Area in a matter of days:

The conflict remains unpredictable:

At some point, many, including me, thought a ceasefire was near - wrongly so. The most recent consensus view was that of a long, drawn-out stalemate - this now looks shaken. Will the recent Ukrainian advances lead to further Russian escalation, or open the path to an end of the conflict?

Rather than making a call on this, I would like to highlight two convictions I continue to maintain:

As I had written in “The End of Putin”, I do not think Putin would survive a military defeat in Ukraine. Dictatorships are based on fear. Fear can only be upheld from a position of power, and embarrassing defeat weakens said power

Further, the Ukrainian army is motivated, the country is fighting for its right to exist and it grows stronger every day with Western arms supplies. Russia’s army is unmotivated, fighting an old man’s dream and its supplies depleting

Summary: The conflict remains unpredictable. However, over the medium term, strong forces work in Ukraine’s favor

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

Equities - I have closed my various shorts on Friday and flipped short-term bullish (see my Twitter for real-time commentary, I also share much of the data going into my work there). Various signs favor another upward squeeze, principally driven by excessively negative positioning as illustrated in AAII sentiment surveys…

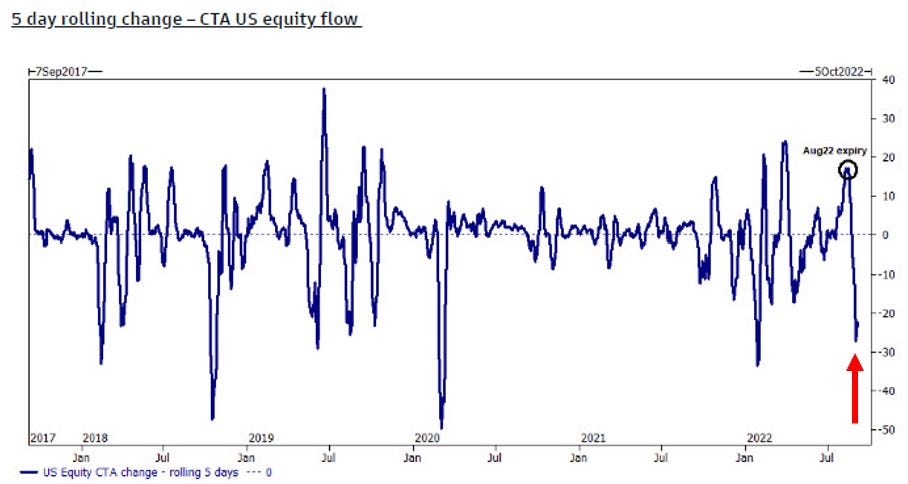

…CTA selling which has become extreme….

… and other data suggesting similarily one-sided views:

Further, nothing moves in a straight line, and both the Yen and US bond yields may take a breather after a strong run. Either way, we’ve come a long way from the August market highs, so I prefer to lock in profits on these shorts rather than ride them through a potential squeeze. To participate in the latter, I’ve bought short-dated out-of-the-money call options (Sept 30, 52 Strike) on Cathie Wood’s ARK ETF as a proxy for high growth, unprofitable Tech, which I deem the fastest horse in such a positioning-driven squeeze. For options, one needs to have a view on both timing and direction, which is the case of me here. If I am right, these calls offer a 3:1-5:1 reward. If I am wrong they will expire worthless. Accordingly, these are only ~1% of my book, with the remainder now in cash

European yields - I remain short Schatz futures (2-Year German government debt). Klaas Knot’s comments (see above) suggest further rate increases, and the aspired ECB terminal rate is now 2.75%. As a side note, should this level be reached, imagine what that would do to the German housing market

Medium term, I maintain my negative view on markets and judge any rally to eventually reverse. Historically, markets only lastingly turned 1-2 quarters before the economy turns. Looking at various cyclical lead indicators, that would take us into mid-2023. Meanwhile, Quantitative Tightening looms large:

The supply of Treasuries is bound to increase to historically high levels of ~$1.5 trillion in 2022 and 2023. Before Covid, this number was ~$500 billion

The Fed owns ~25%-30% of all outstanding US debt. Is this a market that can stand on its own feet, without the Fed’s help? I doubt it. Since 2000, the amount of Treasuries outstanding has tripled, but the average daily volume in the cash market has grown far slower, suggesting an unnatural market

I had written last week about the role of foreign UST buyers. China owns ~$1tr UST debt and has become a geopolitical adversary. If China keeps buying, it finances the US’ efforts against it, from US rearmament to reshoring initiatives

As such, I would look to re-engage in market shorts, should a constellation of asymmetric risk-reward crystallise again, as it did in August

Finally, I once again find it notable that the chorus for a higher inflation target grows, see Harvard’s Jason Furman arguing again for moving it from 2% to 3% last week1. Such a decision might seem technical in nature, but comes with tremendous consequences for asset prices worldwide, so it is worth monitoring this development

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!