Is Inflation Good?

As Central Banks struggle to fight inflation, and China's reopen fuels it, expect the narrative to soon embrace its perceived benefits

Regular readers will be familiar with my view of the tremendous tension between higher interest rates to fight inflation, and a global debt pile that cannot cope with higher rates

We can express this view in simplistic mathematical terminology. There are two levels of interest rates. On the one hand, there is interest rate level X that crushes inflation. On the other hand, there is interest rate level Y which crushes the financial system. The conundrum is that X is likely higher than Y

Over the last few weeks, we found out the level of Y, as many Central Banks “blinked” and slowed their tightening pace out of systemic concerns, despite still raging inflation. Meanwhile, X once again moves higher with one big development - China’s reopening

As the gap between both grows, it gets us closer to a world of “Financial Repression”, where interest rates stay below inflation for a longer period of time. There are perceived benefits to such a world, which I would expect to be emphasised in public discourse, as the presumably inevitable occurs. This post walks through the pros and cons and attempts to answer the question - could inflation actually be good?

As always, the post closes with a view on current markets. Having been short risk assets for most of the year, I switched to long as laid out in “The Last Inning” two weeks ago, and have since added to positions that should do well in “Financial Repression”. I may be early or I may be wrong with this view, however I think this regime shift eventually occurs

In said section I also include a review of the sectors I could see doing well over the next 5-10 years, for those with an asset allocation view long enough to make market timing unnecessary

So, as mentioned, there is an interest rate level X that crushes inflation and an interest rate level Y that crushes the financial system. Y is likely lower than X. Further, Y likely limits how high Central Banks would raise rates, as they would not want to cause a systemic crisis. But what are these levels actually?

I believe, X, the interest rate level needed to crush inflation to be at least 6-7%. Why?

US inflation is driven by consumer spending. However, the US consumer is not sensitive to higher rates. Cash balances are high and in fact, with higher rates, incur decent interest income1. The vast majority of debt is fixed mortgages and typically paid down over its lifetime, unlike many European mortgages that need to be refinanced

So other channels are needed to slow spending. One is unemployment. I discussed in several previous posts e.g. “A Historic Agreement” why I think unemployment will rise much more slowly this time around. Below again the key chart - a unprecedent recession would be needed to wipe out enough vacancies to create slack in the labor market

Now, aside from the consumer, there are two other channels to slow spending, government and corporates

Higher interest rates reduce corporate credit demand, which unlike consumer debt is short term and often floating. However, given the smaller size of the corporate sector in comparison to consumers, again a tremendous amount of destruction would need to occur to slow spending sufficiently

Higher rates also impact government finances. These can be address by spending cuts or higher taxes. I deem both unlikely by a truly meaningful degree, see more below

Whatever the domestic US dynamics, inflationary pressures just received a new push with China’s efforts to reopen its economy

While the official government line remains one of a continuation of strict zero-Covid, many signs now point to a policy exit by Spring ‘23

Keep in mind, the official party line continuously portrayed China’s tough lockdown approach as superior to the West. This narrative needs to be gradually shifted, the elderly need to be sufficiently vaccinated and the weather needs to turn warmer before this turn can be broadly implemented

Either way, zero-Covid stifled Chinese demand, from oil consumption to luxury products to tourism abroad. Unleashing pent-up Chinese demand on a resource-constrained world economy will further feed inflation

All this leads me to believe that the 5.3% “terminal” interest rate Jerome Powell has guided to is insufficient, even if accounting for 6-12 months monetary policy lag. Now, is the right number 6%, 7% or more? In this unprecedented territory, one can only attempt a directional answer (i.e. “higher”). Importantly, the rate would need to stay high for an extended period of time to produce an effect, since, as outlined above, for various reasons transmission is likely limited

Moving on to Y, the interest rate that breaks the financial system. I believe this to be around 4-5%. Why?

First, I define “breaking the financial system” by either a liquidity crisis or default in sovereign markets, or the bankruptcy of a systemically important institution

Following the ‘08/’09 financial crisis, banks are well capitalised and unlikely to be a crisis source. This leaves insurers and pension funds, as recently witnessed in the UK, and sovereign debt markets such as US Treasuries

US Treasuries are the base layer of the financial system. All risk assets are priced off them. Thus, a Treasury market crisis immediately spills over into other asset classes

In October, liquidity dried up in the long-end of the US Treasury market. 10-30 year bonds sold off in freefall, a crisis was close. This triggered a meaningful reaction from the Fed, the Treasury and various other Central Banks, as documented in “The Last Inning” and again depicted in the chart below. This reaction occurred at a ~4.4% yield for 10/30-year US Treasuries

Further, the option of Treasury Buybacks (discussed in last post) is kept on the table, as per 2nd November TBAC minutes. They will likely be implemented at a later stage, or I suspect if 10-30 Year Treasury bonds yields increase again meaningfully2

Now, there is the immediate liquidity crisis risk. But another, more long-term dynamic is also at play, the continuation of government services without large spending cuts or tax increases

While US government debt has a current average maturity of 6.2 years, 26% of it will have to be refinanced next year and another 8% is inflation-linked bonds (TIPS)3. So higher rates for longer soon create a huge budget hole, as illustrated in the chart below. It compares the ‘23 budget for Defence and Healthcare with interest expenses at various interest rate levels. ~$700bn are eventually needed to cover a 5% interest rate and ~$1300bn for a 7% interest rate (in comparison to 2019 interest rates)

Sure, these funds can be found in spending cuts or higher taxes. But either likely runs into tremendous resistance. US social services are already bare bones for a developed nation, and tax increases are not in the country’s DNA, especially in a split Congress

Instead, economic history points to lower than adequate interest rates as path of least resistance to keep government finances balanced, a path already pursued in the aftermath of WWII

Summary: US interest rates would likely need to go to 6-7%+ and stay there for an extended period of time to successfully crush inflation. However, interest rates are likely capped at around 4-5%. Higher levels could cause systemic financial markets risks and tension within government finances

To corroborate the assumptions in this paragraph: Historically, inflation was never brought down without interest rates well above the rate of inflation. While the historic sample may be limited and should thus be read with care, this also points to a 6-7% Fed Funds Rate, assuming core inflation runs ~5%+ for most of 2023

So, Central Banks blinked, China reopens and a 2%+ gap emerges between where interest rates likely will be and where they should be. What will governments and Central Banks do, if they cannot get inflation under control? In my view, they will embrace its perceived positives, which are as follows:

Unwind of inequality

The era of globalisation, low interest rates and Quantitative Easing brought enormous inequality and with it social tension. As asset prices were revalued upwards, economic stakes were redistributed to those who already had a lot. Given the overall pie barley grew, this came the expense of everyone else. Financial achievements taken for granted a generation ago such as home ownership for young middle-class families went out of reach

Quantitative Easing played a large role in these dynamics. Introduced by Ben Bernanke in 2008, this policy explicitly focused on the wealth effect (see quote below). If asset prices are driven up, those who own assets would spend more, benefitting everyone else in the process. Some of that might have happened, but it seems fair to say, after more than a decade of QE, the legacy does not seem as “virtuous” as predicted

Getting rid of an unsustainable debt pile

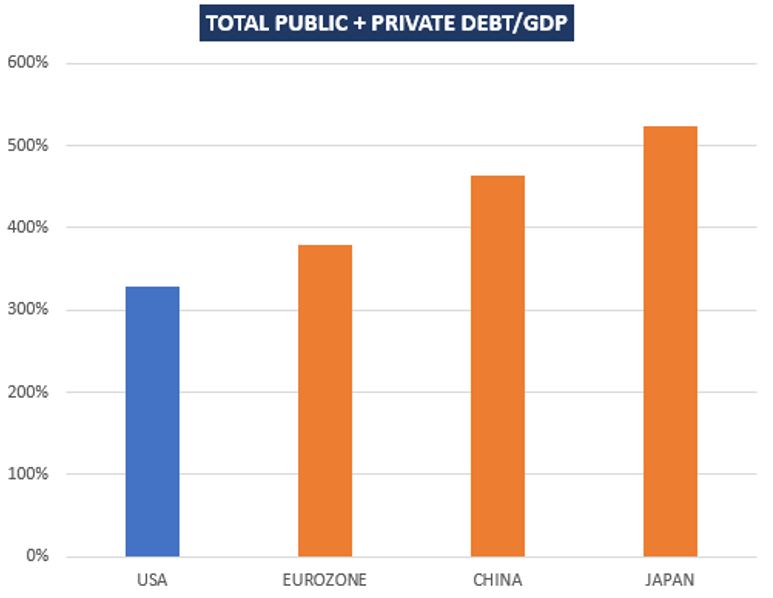

Both public and private debt in Western economies are at extreme levels that frankly seem unlikely to ever be repaid. There are two ways to get rid of excessive national debt. One is default, a socially toxic way that historically bred political extremism. The other way is via “controlled” inflation, as happened e.g. in the post-WWII period in the US

Generally, this process of delevering via inflation, commonly labelled “Financial Repression”, moves wealth from savers to debtors, and thus from old to young. A process the latter group will welcome, after decades of of the inverse

More power to wage earners

Tight labor markets mean more job security, a higher likelihood to find a new role, more negotiating power for higher wages and a lower possibility of one of the most stressful events in adult life - unemployment

Higher domestic industrial investment

The inflation drivers of deglobalisation and reshoring likely increase Western domestic industrial capex. A boost for the Western working and middle class, again the inverse of the past decades

General redistribution of corporate investments

The low interest rate era incentivised corporates to use the “easy way” of boosting earnings per share, buybacks & dividends. The “hard way”, capex and R&D, was neglected, as the chart below shows. This is likely to reverse, as higher cost of capital hinders buybacks/dividends

Summary: As the reality of higher inflation for longer materialises, expect the public debate to shift to the perceived positives of inflation, in particular an unwind of QE-era inequality, delevering, more power to wage earners and higher corporate investments

So all is well? No, it is not. Inflation is bad. Why?

First: most of the effects outlined above are simply due to higher interest rates. These should be a natural feature of a well-growing, balanced economy with adequately low debt levels

Second: inflation is bad because it is a lie. You hold a dollar bill in your hand, trusting it to hold a certain value. But as you hold on to it, that value deteriorates. The promise of price stability in the medium of exchange is broken

So unsurprisingly, inflation has many negative sides, in particular:

The poor hurt the most - The less money you earn, the more of that goes to consumption, in particular of necessities, which bear higher inflation. However, unemployment hurts the poor even more, especially in the US without a social safety net. Accordingly, the worst outcome is high inflation and high unemployment, also known as stagflation

Inflation is not static - Politics cannot simply control inflation at an opportune level of say 4%. Higher inflation for longer changes consumers’ inflation expectations. They will start to bring consumption forward, thereby increasing inflation further

Disruption to public life - Excessive money supply distorts labor markets. The 1970s were notorious for continued strike action in often neuralgic industries. However, we are still far from anything like that

Misallocation of capital - The Yield Curve Control regime I see as most likely (see “The Last Inning”) distorts capital allocation decisions just as QE did. It likely produces inefficient economic outcomes that only turn obvious with a multi-year time lag

Eventually, high unemployment - The endgame for high inflation environments has frequently been stagflation i.e. high inflation AND high unemployment as years of capital misallocation take their toll. The “Misery Index” measures this by simply combining both metrics

My sense is the public discourse over the next 6-12 months shifts to perceiving inflation as “not that bad”, and it then only turns fundamentally against it when the Misery Index is high

The experience of the 1970s can serve as guide. Paul Volcker was able to fight inflation aggressively by bringing unemployment above 10%, because the public was tired of it after 15 years. His predecessor Arthur Burns did not enjoy the same public support, something he laments in his seminal speech “The Anguish of Central Banking” a year after his resignation in 1979

Summary: No, inflation is not good. Yes, a higher interest rate environment brings many benefits, but these are accompanied by the corrosive effects inflation has on the economic edifice, from social discontent to misallocated capital

In an ideal world, excessive global debt would be restructured so economic growth could resume without restraint and capital could be allocated efficiently. With too many actors and the fear of uncontrollable second order effects, this seems highly unrealistic

In a realistic world, “Financial Repression” i.e. a prolonged time of elevated inflation that reduces leverage in a stealth way seems the most likely outcome

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

The work my team and I do, which is based on tracking hundreds of real-time economic data points as well as liquidity metrics and guidance, offers two lenses. Today, I’ve split this section accordingly

Long-term Trends

The first lens is focussed on the recognition of broad, long-term trends. This is the perspective of the capital allocator, with investment decisions for a multi-year time frame. Please see my conclusion on which sectors and theme likely outperform over the next 5-10 years, assuming the regime moves to Financial Repression

Banks - the thesis is simple here, a higher interest rate world means more income for banks. This is particular pertinent to Europe, where banks adapted their cost structures to a decade of negative rates. On the downside, expect governments to target some of these excess profits, especially on higher reserve income not passed on to consumers via higher deposit rates

Industrials - Looking at the challenges for the next decade, from energy to deglobalisation, all these require heavy investment, a boost for capex-related industries

Defence - The sad truth is that the world has become less safe. In my view, Taiwan is biggest risk to markets (and the world) in 2023. See Anthony Blinken’s and the head of the US Navy’s recent comments about a significantly accelerated timeline for China action on Taiwan

Royalty Businesses incl. Software - any income stream with high pricing power created by a high-margin business thrives in a financial repression world. Software fits this characteristic, often mission-critical and a small share of customers’ cost. The biggest risk here is multiple compression

Nuclear - Climate change is a reality, just look at the European thermometers in late October. Nuclear stands out as constant baseload technology complementary to intermittent renewable source. Both in combination can create carbon emission-free electricity production. Many nations committed to more Nuclear plants, this will also drive Uranium prices

Oil & Gas - the world is short energy and continues to underinvest, yet oil demand remains near peak levels. The same logic applies to many other Commodities. Further, they have become a geopolitical weapon. However, these sectors are highly cyclical, making timing critical. I also find a higher tax burden likely, to account for environmental stress

Alternative Energy - energy scarcity and climate change dramatically increase the need for alternative energy sources, from Renewables to battery storage. Differently to oil & gas, this theme also enjoys unequivocal government support. The US Department of Energy earmarked $348bn in grants and loans to the sector until 2026

Value stocks - A high inflation and high interest rate regime is good for low-multiple stocks. Value was one of the best performing categories in the 1970s. Healthcare is worth highlighting in particular, where valuations are low and secular drivers strong. I would even include Biotech here, where many companies still trade below/near net-cash levels

Distressed Debt - the transition from a low- to a high cost of debt economy should cause an avalanche of debt restructurings. Conversely, any strategies relying on a low cost of debt likely do poorly

Gold & possibly Bitcoin - Gold is the classic storage-of-value trade, destined for an era of “Financial Repression”. Bitcoin is its less tested great-grandchild, it also shows some high-beta characteristics, so the jury is still out on it

The conspicuously absent theme High-Growth Tech, the biggest winner of the last decade. There is no doubt that technological adoption accelerates and today happens faster than ever. However, two dynamics work against it

First - a high inflation regime compresses valuation multiples. This effect is more pronounced the further cash flows lie in the future, which is the case for High-Growth Tech

Second - we just passed a giant bubble, manifested not only in extreme valuations, but also in misallocated capital that takes years to clean up, from overstaffed FANGs to overcapitalised start-ups pushing already broken business models

High-growth Tech investors need to make sure their investment thesis is strong enough to withstand potentially severe multiple compression

For the VC industry, I see a growing trend to deploy the $290bn dry powder in public markets. This may be successful, but it comes with enormous risk

The private market skillset is fundamental analysis and relationship-building. The public market skillset is fundamental analysis, positioning and macro. The latter two explain 70% of what moves a stock and are a complex art in itself. The 30% due to fundamentals in public markets is very, very crowded (see pervious post “It’s All One Big Trade”)

My humble view - it may be best for private market VCs to wait and be patient with their excess capital, rather than burn it on macro-driven public market trades. A private market focus on the new tailwind sectors may be more promising than trying to resurrect the old bubble in public markets, which, if history is any precedent, is unlikely to also be the next one

Short-term Trends

This brings me to the second lens, which are the short-term trends. These are often driven by positioning, and I actively trade these. Accordingly, my stance changes frequently, as documented in many previous posts.

Risk assets - As laid out two weeks ago and in today’s post, I remain long risk assets and have added further to positions that benefit from Financial Repression, mainly via Energy and Oil Fields Services (XLE, OIH, XOP, Drillers), Biotech (XBI), Homebuilders (XHB), European Banks (SX7P, hedged with SX5E), US Large Cap Banks (XLF), US Healthcare (XLV) and also China Tech (KWEB, see more below). Please notice that this composition materially differs from generic market longs (i.e. S&P 500). It is also very different to the average equity hedge fund long book, where energy remains a big short. On that note, hedge fund exposure remains universally bearish (see last post, or chart below), which continues to provide the fuel this rally needs

China Tech - As mentioned in the last post, I own KWEB since the Monday several China-driven funds liquidated their holdings. This is currently the most disliked asset class in the world, which is why any small positive news easily cause tremendous upside. I also notice that Chinese mainland investors increased their holdings in these offshore ADRs while foreigners have been selling. As a timely contrarian indicator, Tiger Global just halted all China investments

Financial Repression - In my view, the current stage can be seen as first inning of this new regime. I’ve positioned for this by acquiring Gold. I had also bought a small holding of Bitcoin and Ethereum, which I sold again following the developments around crypto-exchange FTX. In general, my USD exposure is now greatly reduced, and I am mostly either in risk assets (see above) or Gold. As mentioned before, I may be early with this view and I may change my stance again

US Large Cap Tech - This sector is in purgatory. Poor earnings, unmotivated employees (“rest and vest”), high valuation (Amazon), more cyclicality than secular growth, regulatory headwinds, TMT hedge funds with redemptions needing to sell - you name it, the list is long and I personally think if anything this area remains a short

Finally, I would expect the current risk rally to end when enough believe in the beginning of a new bull market, and positioning becomes once again one-sided on the bullish side. This could be some time between mid/late November and possibly even into January. I would expect another potentially steep sell-off then, possibly to new lows, as the economic slowdown intensifies while corporate earnings rapidly decline. However, the expectation of imminent new lows is very prevalent, thus some other outcome may occur

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!

DISCLAIMER:

The information contained in the material on this website article reflects only the views of its author (Florian Kronawitter) in a strictly personal capacity and do not reflect the views of White Square Capital LLP and/or Sophia Group LLP. This website article is only for information purposes, and it is not intended to be, nor should it be construed or used as, investment, tax or legal advice, any recommendation or opinion regarding the appropriateness or suitability of any investment or strategy, or an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, an interest in any security, including an interest in any private fund or account or any other private fund or account advised by White Square Capital LLP, Sophia Group LLP or any of its affiliates. Nothing on this website article should be taken as a recommendation or endorsement of a particular investment, adviser or other service or product or to any material submitted by third parties or linked to from this website. Nor should anything on this website article be taken as an invitation or inducement to engage in investment activities. In addition, we do not offer any advice regarding the nature, potential value or suitability of any particular investment, security or investment strategy and the information provided is not tailored to any individual requirements.

The content of this website article does not constitute investment advice and you should not rely on any material on this website article to make (or refrain from making) any decision or take (or refrain from taking) any action.

The investments and services mentioned on this article website may not be suitable for you. If advice is required you should contact your own Independent Financial Adviser.

The information in this article website is intended to inform and educate readers and the wider community. No representation is made that any of the views and opinions expressed by the author will be achieved, in whole or in part. This information is as of the date indicated, is not complete and is subject to change. Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although believed to be reliable, has not been independently verified. The author is not responsible for errors or omissions from these sources. No representation is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of information and the author assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise such information. At the time of writing, the author, or a family member of the author, may hold a significant long or short financial interest in any of securities, issuers and/or sectors discussed. This should not be taken as a recommendation by the author to invest (or refrain from investing) in any securities, issuers and/or sectors, and the author may trade in and out of this position without notice.

This is true for money market funds and T-Bills. If you hold your cash at a US bank, you miss out on interest payments, with most bank deposits still offering near 0

At this point, I again want to highlight how QT has not evolved the way the Fed planned it. See former SOMA head Patricia Zobel’s comments here, expecting QT to be funded by the RRP as banks would increase their deposit rate. The opposite is the case so far

Some share of TIPS obviously also mature next year

In a financial repression scenario (ie negative real rates ) how would being a lender (ie - bullish banks ) make sense ?

Thanks a lot for this. And sure sounds good, thank you for asking