It‘s All About Housing

The market at the center of inflation. Plus more on Europe

The US housing market is at the heart of the inflation debate. With ~40%, shelter represents the biggest component in the consumer-price-index (CPI). More so, it is an essential social issue. Drastic housing cost increases cause tremendous stress and anxiety for those who lack the resources to keep up. The poorest quarter of Americans spend more than half their income on rent

This post looks at the current state of the US housing market, ties it to the inflation debate and derives the implications for global capital markets

While equity markets have been hit by the Fed’s pivot to fighting inflation, the US housing market remains absolutely on fire

Inventories have never been as low for this time of year…

…days-on-the-market are at a record low for this time of year…

…and median prices jumped 1.3% the past week, implying at least another 10-12% increase for 2022, after a blockbuster year 2021

Looking at these metrics, this is a historically tight market, with tremendous upward pressure on prices

Ok, but why is this important?

House prices are up because all the printed money has to go somewhere. People with excess cash are buying because they’re scared of inflation (for the same reason, no-one wants to sell)

If affluent individuals and institutional investors buy houses to park money, they drive prices up for weaker market participants such as first-time buyers

In turn, these can’t afford to buy anymore and have to rent, driving up rents for everyone else

And rents are going up at an aggressive pace

In many cities, in particular across the sun-belt (Arizona, Texas, New Mexico, Florida etc), rents are up 40% or more

Rent increases of 10%-40% are a social catastrophe for many. They force relocation and homelessness; They are a regressive tax that crushes people the more, the less they have

Breaking this dynamic is one of the biggest levers the Fed has to slow inflation. But what can they do?

It gets a bit more technical here, but bear with me:

For the housing market, the most important interest rate is the 30-year government bond. Most house purchases involve a mortgage. Mortgages typically have 30 year terms, and are priced as a spread over said rate

To slow down the housing market, the cost of mortgages would have to increase. For that to happen, the 30-year government bond yield needs to go up

The Fed however only sets the overnight interest rate. So when people are saying the Fed should increase rates, they refer to an increase in the rate paid on short-term deposits

Interest rates with a longer duration, such as 1-year, 5-year or 30-year bonds, are priced by the market. The market takes a guess what the overnight rate would be1 over these timeframes

So what can happen, the Fed can increase the overnight rate to, say 2%, but the 30-year bond trades below that, say 1.8%. The market might assume future overnight rates to be lower than now, for example because it expects a recession. Or there is too much liquidity, so the market bids anything with yield.2 Either way, when long-term rates are below short term rates, this is called Yield Curve Inversion

At the moment, we are quite close to that. After the Fed has changed its tone on inflation, short-term rates increased as desired. Long-term yields however, such as the 30-year government bond, remain stubbornly low3

But in order to slow down housing, these long-term yields would need to go up! So what now? Is the Fed stuck?

Not at all, there is a solution. That solution is called Quantitative Tightening (QT, see this post for more details)

Over the past decade, the Fed bought ~$8tr of government bonds and mortgages (MBS, more below) in a process called Quantitative Easing (QE). This pushed asset prices up across the board, it was meant to get people to spend more by making them feel wealthier

The easiest way to increase long-term rates is to reverse this process and to sell those bonds with long duration back into the market. This increases the supply, and all else being equal, bond prices fall which means their yield goes up (= Quantitative Tightening)

The excerpt below, taken from the 26nd January FOMC statement, is an ominous sign that exactly that, QT, is now firmly on the table for the Fed

Now, to interpret that sentence, one needs to know that most long duration bonds the Fed owns are Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS), not treasuries. So accordingly, if the Fed wants to primarily hold treasuries, it has to sell these long dated MBS4, which would be nothing but QT focussed on long-term rates

This is not the only indication about the imminence of QT. Several Fed governors, such as Esther George (Kansas) or Mary Daly (San Francisco), have recently been vocal about implementing QT sooner than planned, preparing the market for a shift in thinking at the Fed

QT is looming large, and as discussed before, it is negative for all asset prices. This is because all Western assets are priced off long-term US government bonds (the perceived “risk-free rate”). So if the yield on these bonds goes up, the prices of other assets - all being equal - drop

Conclusion: The inflationary dynamics in the US housing market represent a huge social problem. The best way to address them is via QT, and this is in the making. QT is negative for all asset prices. In light of this, as mentioned, any market rallies are likely bear market rallies, which I continue to recommend as opportunities to sell. This likely continues until the Fed turns (or inflation abates), neither of which I deem likely near term

ADDENDUM: Inflation in Europe

Western economies and financial markets are closely connected, and even if Christine Lagarde likes to pretend otherwise, inflation is therefore also an European problem

Whether it is housing in the US, or energy prices in Europe, it is an expression of the same underlying phenomenon, too much money around

Inflationary pressures in the Euro-Area are increasing. Yesterday’s data release for Eurozone January inflation came out at 5.1%

This was sequentially higher instead of an expected down. It was also the biggest forecast surprise on record:

While energy prices are to blame for the headline number, core inflation, which excludes energy, is also trending up

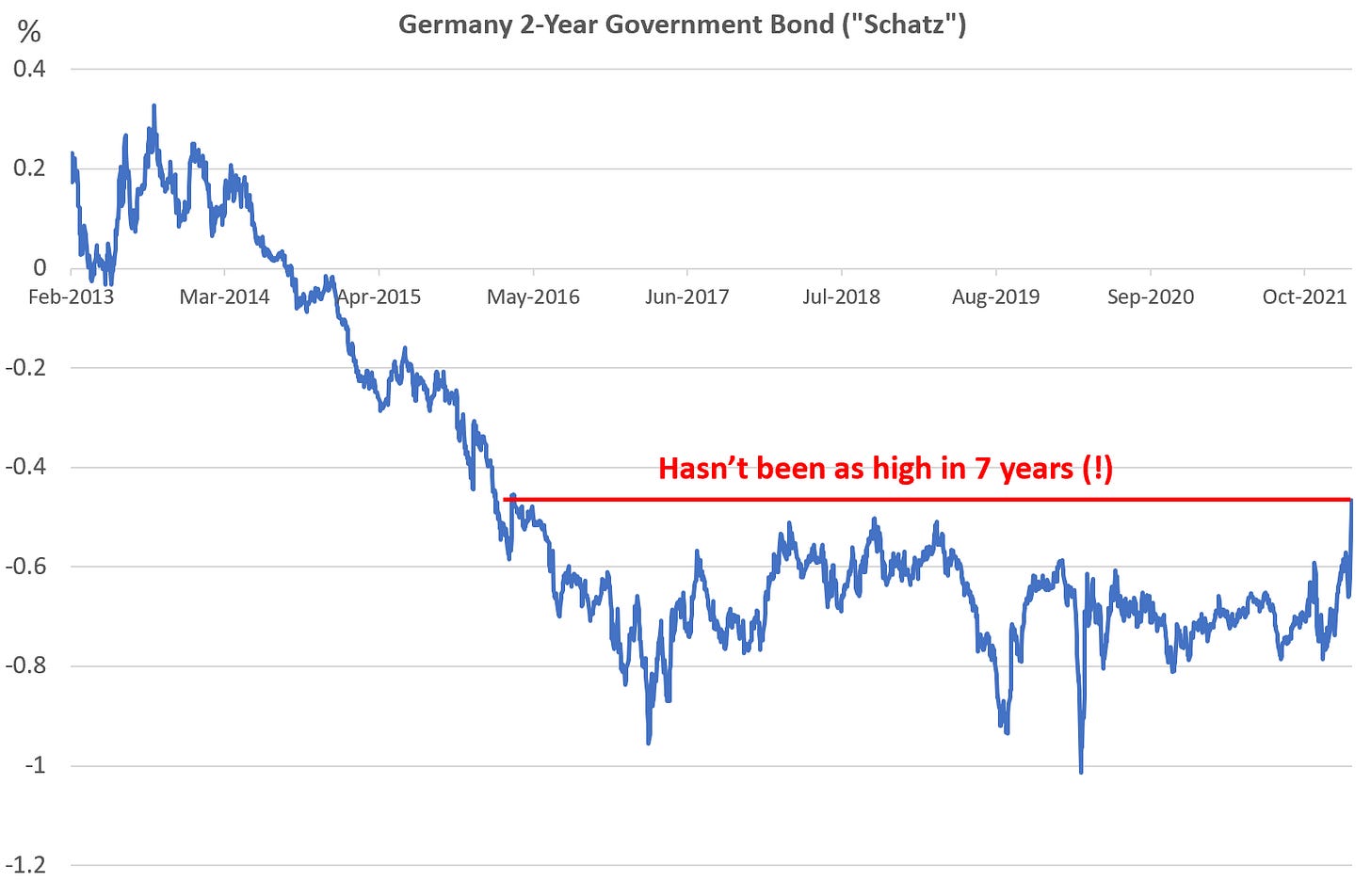

So it’s no surprise that this giant is slowly awaking from its long sleep:

As mentioned in October in “Europe and its Banks“, the biggest beneficiaries of structurally higher interest rates are European banks, which I continue to like on a relative basis

To be precise, the market also adds a term premium

Interestingly, Kansas Fed governor Ester George estimated in a recent speech that the 10-yr government bond yield would be 150bps higher in absence of QE

Some in the market believe this is because a slowdown in economic growth is imminent, based on lead indicators from manufacturing sectors. I believe it is because of excess liquidity, and weakness in said lead indicators reflects a rotation in spending from goods to services (e.g. hospitality etc.) as the economy reopens

To be entirely precise, in order to achieve that, the Fed could also let the MBS run off, but given that they are mostly long-duration, this process would take decades