Lessons from History

What can the past tell us about today's economy?

History does not repeat, but it rhymes. It is the reflection of human behavioral traits which remain constant over time, with greed and fear the most prominent

As the world economy stands on the cusp of a recession (see last week’s post), it is worthwhile to compare how these unfolded in the past, with similar patterns likely repeated today

This post reviews the past five US recessions, with a particular focus on real disposable income. This economic metric describes nothing but what people have left in their pocket once inflation is deducted. Today, with inflation seemingly on the way out, real income has increased. This lead many, from the FT to Goldman Sachs, to believe a re-acceleration of the economy is on the horizon

History shows that this conclusion is likely wrong, with higher real income in fact a hallmark of recessionary periods. Today’s post explains why this is the case, and highlights some further similarities between past recessions and today

As always, the post concludes with an outlook on current markets. Right now, there is a yawning gap between economic reality and what capital markets price in. I expect this gap to close, with the bond market in the lead and equities soon to follow, and am positioned for it with long bonds and short cyclical equities

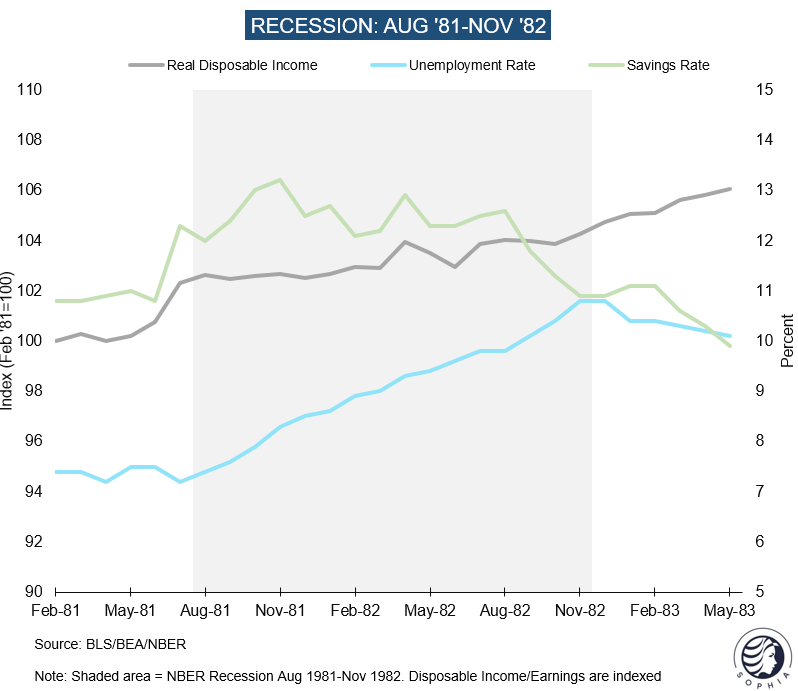

Let’s dive in and start with the 1981-1982 recession

In 1979, the Iranian revolution caused an already high oil price to significantly spike. This fuelled US inflation, which had been rampant for a decade and the populace tired of it. Fed Chair Paul Volcker had a mandate to kill inflation, even at the cost of a slowdown, and raised interest rates to 20%. The tightening from both energy and monetary policy caused a deep 14-month recession

Here is the peculiar part: Real disposable income went up, and most sharply so just before the recession unfolded. What was going on?

It’s simple. Inflation declined as the recession hit, so prices came down. However, wage growth only slowed with a lag, so real income went up, just like today

Why did this not translate into higher consumption? The answer has to do with fear. As corporates laid off staff to protect their margins, unemployment went up and people worried about their future. Instead of spending,` they decided to save more

The next recession unfolded in August 1990 and lasted 8 months

A lengthy expansion followed Volcker’s inflation fight, during which real estate prices rose to precipitous highs and the Fed in response increased interest rates to a 9.8% high in 1989. The monetary tightening slowed the economy with a lag, while the Iraq-Kuweit-US Desert War in August 1990 caused another oil price shock. Once again, high energy costs and monetary tightening triggered this recession

Just as today, real disposable income increased at the onset of the downturn. However, it subsequently declined as the higher oil price this time coincided with the recession and squeezed consumers pockets. Consumers again reacted to higher unemployment with a higher savings rate

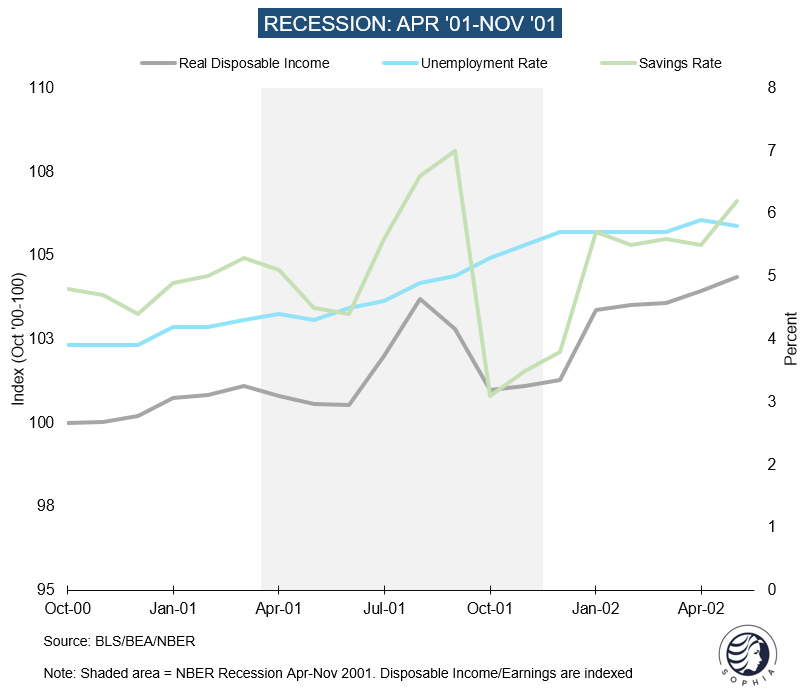

The longest period of uninterrupted US economic growth ensued, to end with the 2001 New Economy recession

Following several interest rate hikes, the dot-com bubble burst in early 2000 and the Nasdaq lost 75% with 18 months. However, Tech was still a small part of the economy and Alan Greenspan, Fed Chairman at the time, reacted very aggressively to the slowdown, cutting interest rates from ~7% to 1.75% within a year, so the recession only lasted ~7 months

Again, real disposable income, the savings rate and unemployment all rose, a by now familiar pattern

Greenspan’s aggressive rate cuts set the stage for the next recession six years later - the Great Financial Crisis

The ultra-low interest policies created an enormous real estate bubble, accompanied by careless lending, particularly in subprime mortgages

Interest rates increased from 1% in ‘02 to 5.25% in 2006, but this was too late and too little to prevent the bubble. Nevertheless, it did slow the economy, which also suffered from higher oil prices driven by Chinese demand. Monetary tightening, higher energy cost and bubble aftermath all combined to the worst economic crisis since the 1930s

Still, even during this 18-month recession, real disposable income went up, as did the savings rate and unemployment

A long, but slow expansion followed, with some recession scares on the way which could all be averted (‘11, ‘16 and ‘19). The next downturn only occurred when Covid-19 hit the world

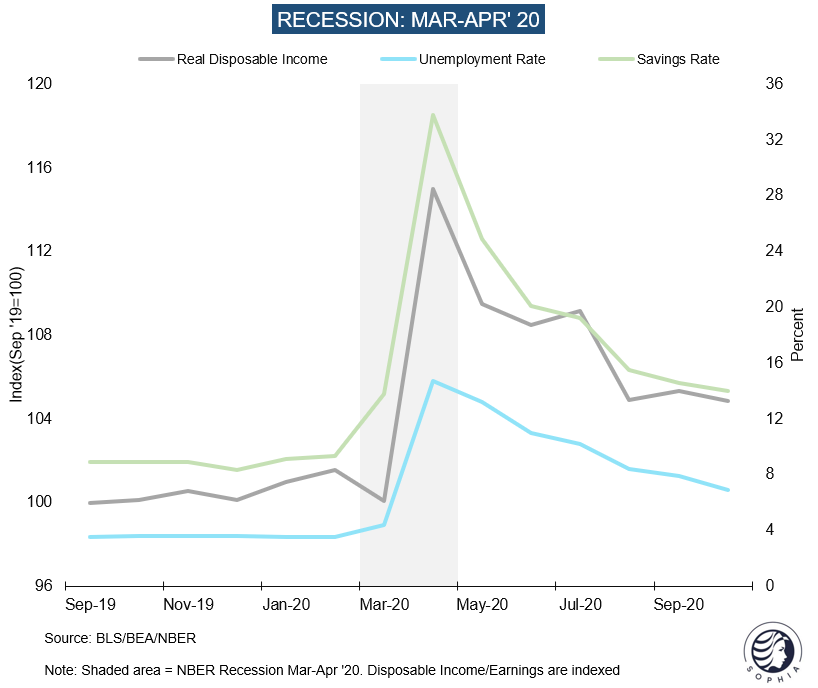

We are all familiar with these most recent events, where lockdowns froze economic activity, so I just want to again point out how real disposable income, the savings rate and unemployment all rose in lockstep

Let’s summarise what we’ve just reviewed, first with a look at real disposable income

Aside of 1990, all recessions, often already in their onset, saw an increase in real disposable income - just as we see today

However, as consumers were fearful about their future amidst rising unemployment, this did not turn into higher consumption and thus did not prevent or alleviate the recession

As such, the current increase in real disposable income is a recessionary sign, rather than reason to believe in a re-acceleration of the economy

Some further interesting commonalities stand out

Four out of five recessions saw monetary tightening in their runup (Covid-19 the exemption)

Three recessions saw a prior squeeze in energy costs (1981, 1990, 2008)

Three recessions saw a bubble burst (1990, 2001, 2008)

None of these drivers were present in the “false alarms” since the Great Financial Crisis (‘11,’16,’19) when a recession each time was avoided

Today’s economy combines all three drivers - (1) a prior squeeze in energy costs due to Covid-19/ESG/Ukraine, (2) severe monetary tightening as the Fed raised rates from 0 to 4.75% and (3) a burst bubble, in this case housing and Tech

Now, all past five recessions had one dynamic in common: job losses. This brings us back to the central question for this cycle - will unemployment increase?

I’ve already made the case in my last two posts that this is unfortunately, likely the case, despite the various employment tailwinds such as Boomer mass retirements

The evidence has hardened further since. Looking at official productivity data, the past 6 months have seen a notable decline. In other words, the output per employee has gone down markedly

The official data above is somewhat outdated, but we can get a forward-looking view, if we deduct the Employment score from the New Orders score in yesterday’s ISM Manufacturing Purchasing Manager survey, to derive a “New Orders per Employee” relationship. It indicates idleness in manufacturing that historically corresponded to mass layoffs

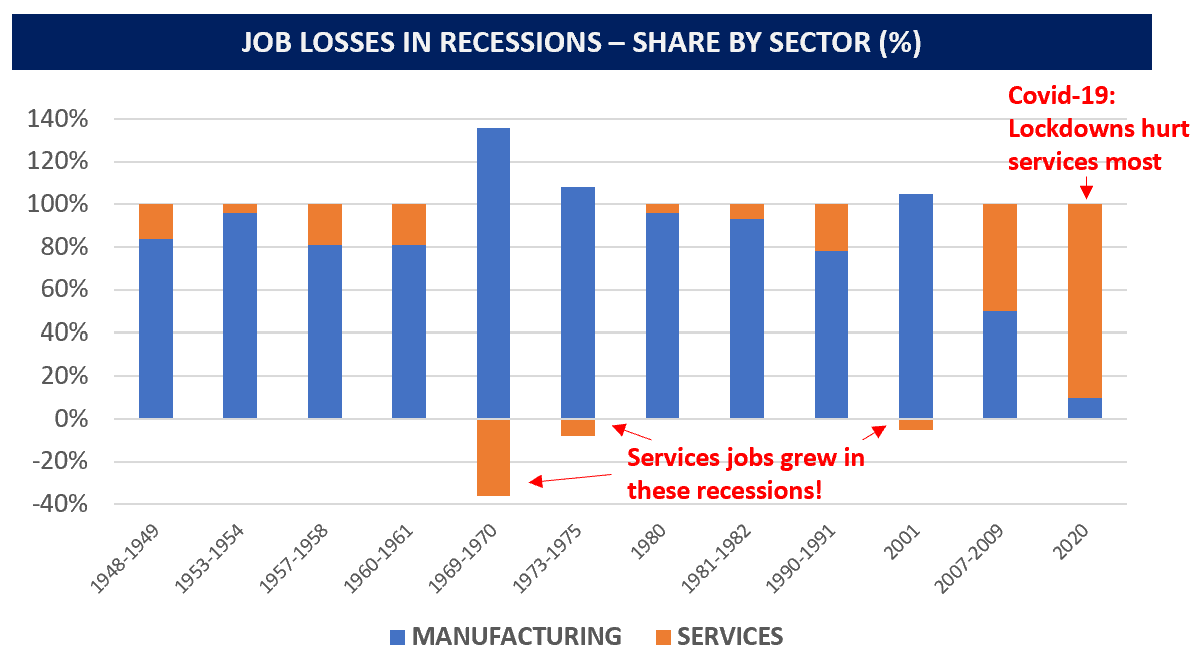

Now, you may wonder - why the focus on manufacturing? After all, the vast majority of today’s US economy is composed of services. The reason is simple: Historically, manufacturing provided the lion share of layoffs, at times even more than 100%

However, there is no doubt that today’s job market is very tight. Companies may hesitate to fire, as they worry roles are hard to fill later on

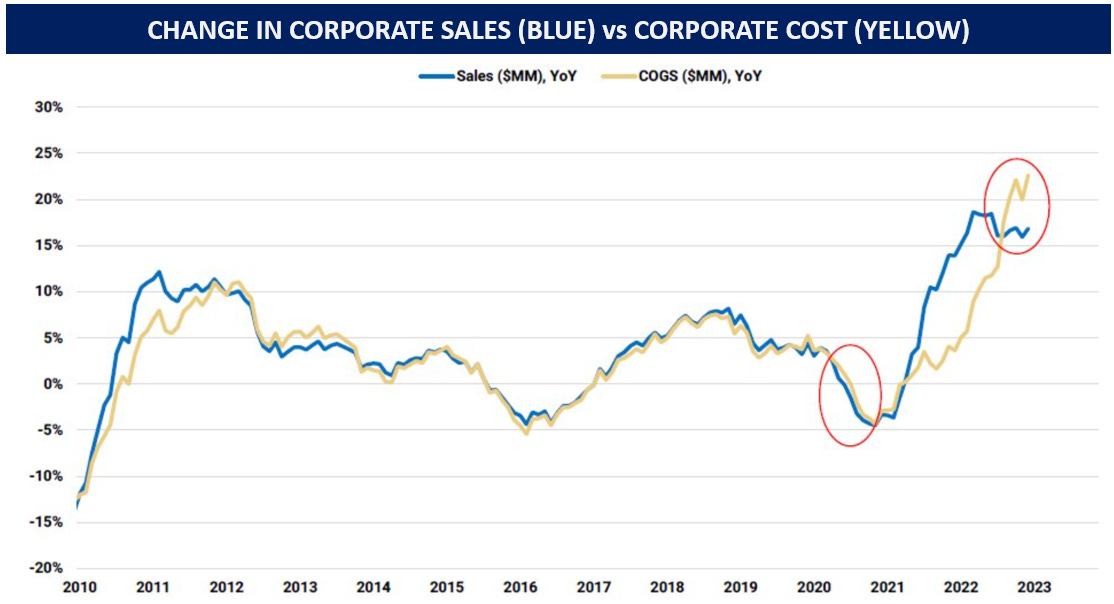

I assume this hesitancy soon ends. Corporate margins are under severe pressure, as costs have grown much faster than sales over the past 6-9 months. Especially in the US, executive compensation is tied to near-term profitability targets and share price performance, providing much incentive to cut cost. Unsurprisingly, the current earnings season has seen an outpour of layoff announcements (see last post), with Paypal and Philips (7%/ 13% of workforce) added to the list this week

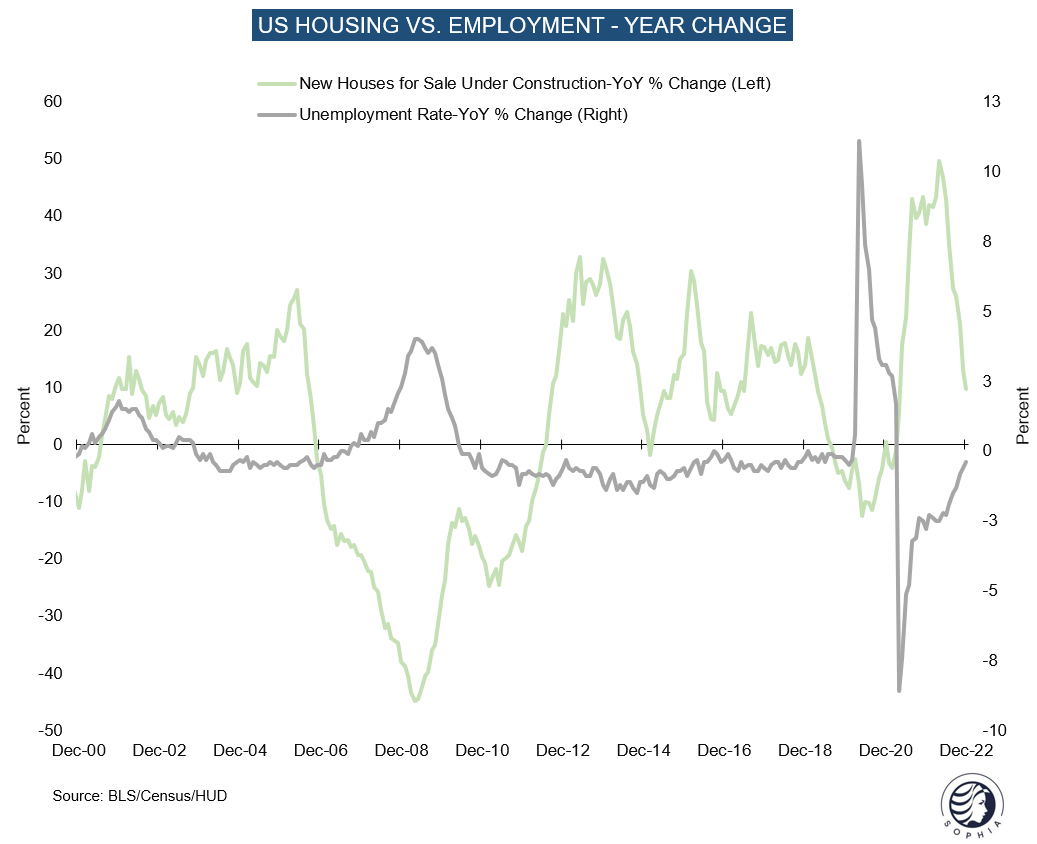

Finally, housing lead indicators such as building permits cratered over the past year, however, construction employment is still high, as the large backlog is worked off. This is nearing an end, so construction employment is likely to decline soon

Conclusion: An abundance of signs now points to an increase in unemployment over the coming quarters. This will affect consumer behavior and amplify the downturn, which likely resembles a “hard landing”. On this, please keep in mind:

Inflation boom-bust recessions were common in the 1970s, with four such cycles between 1970 and 1982

The huge difference this time is the enormous amount of global debt

A hard landing as predicted leads to mass credit events, driven by lower revenue, lower tax intake, higher refinancing needs etc. etc.

This is why I continue to see a return of central bank intervention and QE later this year as only way out

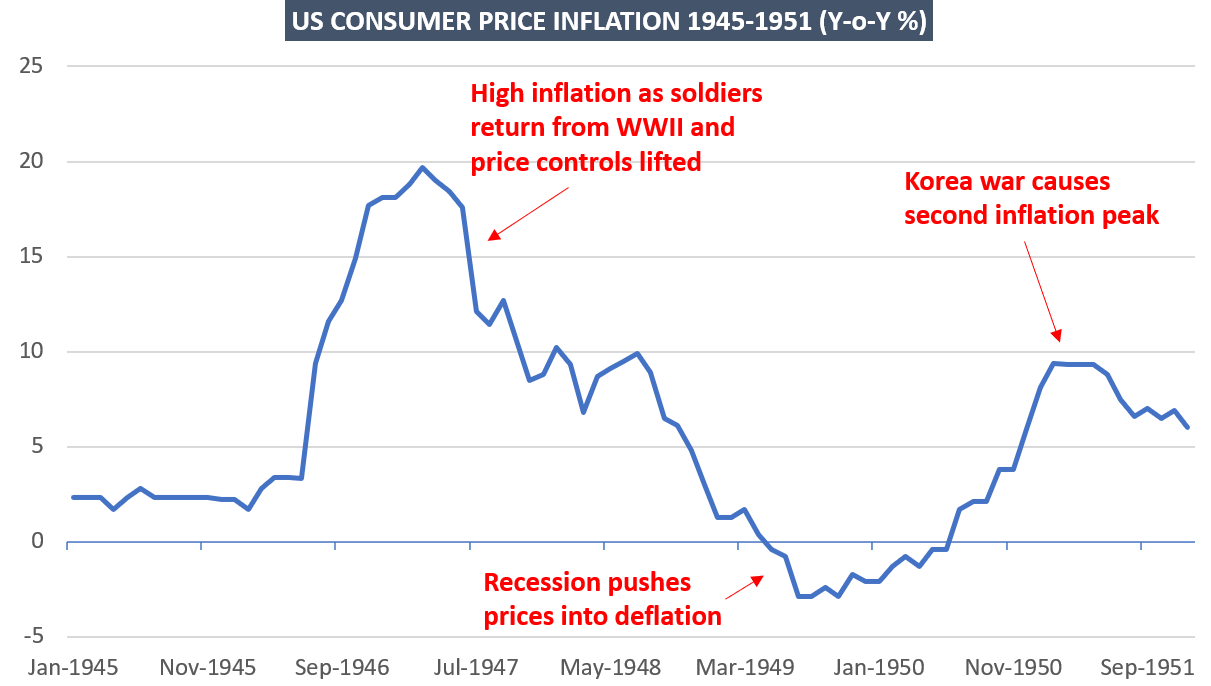

Rather than the 1970s, the post-WWII period may provide a better analogy to today. Public debt was comparably high and the late 1940s shaped by a inflation-deflation-inflation yo-yo

While there are also many differences, I nevertheless see the below chart as a possible, or even likely, template for today’s evolution of inflation

The inflationary drivers commodity underinvestment, deglobalisation and demographic cliff are likely only temporarily submerged by the unfolding downturn, and likely return as the economic cycle turns up again in late ‘23/early ‘24

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

The first challenge in investing is to understand the economic context. The second is to apply it. This involves an understanding of liquidity, which is driven by Central Bank policies, and positioning, which is what everyone else thinks. As mentioned in the introduction, I see a yawning gap between what the market currently prices and what economic data dictates, which I apply to my investments as follows

Bonds - This asset class is the “smartest”, with no meme stocks or retail participation. US Treasury bonds are trading towards a “hard landing”, but still leave plenty of upside should it materialise in the coming months. TLT (20-30 year bonds) remains my biggest position, with additional option bets on Fed emergency cuts later in the year. Please note, for the long term, ie the next 5-10 years, US government bonds are likely not a great holding as financial repression (= rates lower than inflation) is likely needed to fund the ever growing deficit. However, this dynamic only resurfaces as/if inflation accelerates again in the next cyclical upleg

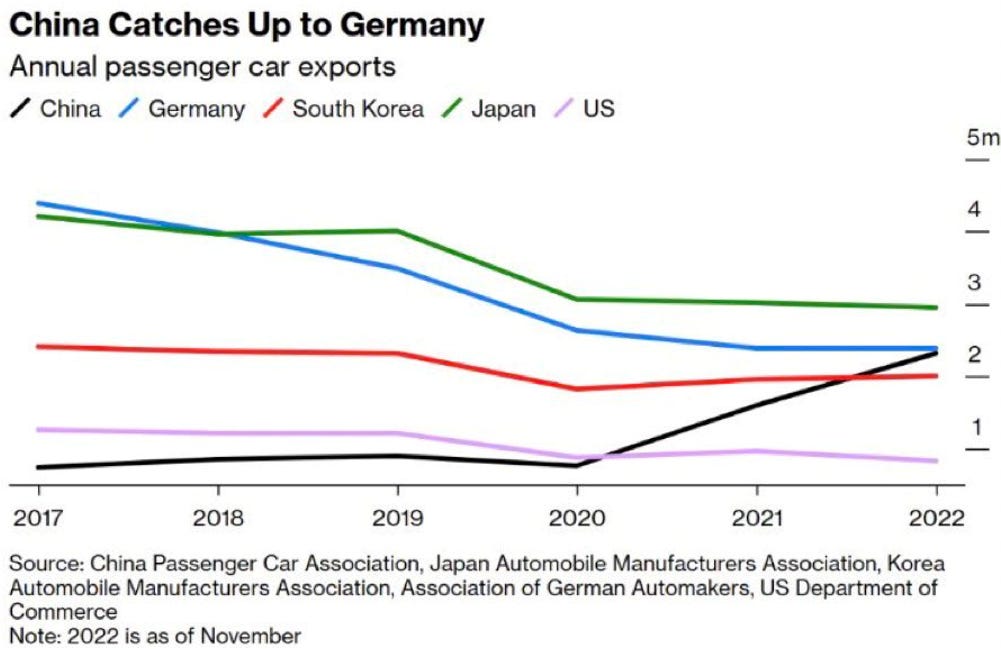

Equities - As laid out in “The Most Important Chart for Markets“ and “The Observer Effect“, I was constructive on equities at the beginning of the year. With now very stretched positioning, this has changed (see last post) and I am short cyclicals including Commodity Producers, European Industrials and Autos. All had huge rallies and are near all time highs. All have historically done poorly in a hard landing. Autos stand out as high-cost discretionary consumer good. Tesla’s 20% price cuts were just followed by Ford and are likely to shake the industry, while cheap Chinese competition floods the market

This portfolio composition of long bonds / short equities is an unusual variation of the 60/40 long bonds / long equities setup that dominated the 2000s, so to speak a “60/-40” book. In a hard landing, bonds should rally and stocks go down. Should I be wrong with my views and a economic reacceleration materialises, bonds will fall, however, equities likely too, as higher bond yields compress their valuation multiple. This approach loses if yields go higher, but stocks do to - possible, but a historic anomaly

US inflation - Credit card data points to decent retail sales in January. This is likely driven by wage contracts that reset that month. However, so do many bills, which is why the January CPI print could come in hotter than expected. Beyond that however, it seems unlikely that inflation accelerates while money supply shrinks and unemployment likely rises. In my view, inflation likely makes a comeback when the economic cycle turns up again (Q4 ‘23?), aided by the likely inevitable return of QE and/or other supportive Central Bank measures

I remain of the view that, just like in the past 70 years, equities follow the economy. The economy follows its various leads, from monetary tightening to higher energy cost, with a lag, as today’s budget decisions are tomorrow’s revenues. This points to further economic downside in the coming quarters and an upturn around late 2023, which - if history is any guide - is likely frontrun by markets by a few months. As such, I currently expect the bear market to end in Q3 ‘23, while accepting this date to be a moving target

great article, thanks!

Those that don't remember history are doomed to repeat it. Well Done!