Long Term Investing

The synthesis of my learnings (Part III)

Last week’s post introduced investing with a time horizon of several months to a few years, where one is rewarded for enduring the discomfort of investing when everything points the other way

Today’s post will address investment decisions made for many years to several decades. With a long-term view, timing the ebb and flow of the collective mood is less important, while other aspects gain more relevance

When investing with a time horizon of many years to decades, the most logical way is to invest in equities

The stock market is a reflection of the economy, and the economy is a reflection of all the humans participating in it

And what most humans have in common is that every day they strive to be a somewhat better version of themselves than the day before

In the long run this will sum up as the aggregate of all these constant efforts to improve. This is particularly true for countries with a stable rule of law and a primate of commerce

Why equities? They are the riskiest part of the capital structure (after mezzanine and debt). In the long run, this risk is balanced out so it makes sense to go higher up the risk curve

In order to invest in equities, for a long time the best strategy was to follow Warren Buffet’s playbook of buying “great companies at a good price”. Great companies according to him would be determined using these criteria:

Growth: A strong product within a growing market

Moat: Unique characteristics that protect the business from its competition

Brand: A well-recognised brand that keeps customers coming back

Predictability: Stability protecting from negative surprises

In a world of steady progress, supported by population growth, a rising middle class and political stability, consumer staples such as Coca-Cola, Gillette or Heinz fit this bill perfectly

Yet, around 2010 the approach stopped working. Buffet’s holding company Berkshire Hathaway has underperformed the market since, and the method feels intuitively somewhat outdated

How so, what happened?

Let’s look at the criteria again in the context of today’s economic order:

Growth: The Western world has gone “ex-growth”, mainly as a consequence of declining birth rates as well as excessive debt in both the private and public sector1. Today, there are much fewer growth-companies around than even 20 years ago, and they are typically not consumer brands

Consumer brands need the traditional GDP-growth drivers of an expanding population2 as well as a rising middle class to grow their top line

Absent of that, businesses still want to increase profits. If sales stall, they do so by reducing cost and become more efficient

Accordingly, today’s stock market darlings are companies that enable these cost reductions and efficiency gains. You guessed correctly, these are the software, e-commerce, big-data companies, in contrast to consumer brands

Moats: The traditional moats have become less defensible. With 0% interest rates and trillions of dollars pushed out of safe government debt into riskier investments, capital is not an obstacle anymore in the attempt to attack existing moats

Below is a chart of the billions of cumulative losses by some well-known start-ups, investments done with the promise of eventual profitability.

These kind of investments were impossible in the pre-financial crisis economy. A higher cost of capital would have prevented capital from being applied to these riskier ventures in the same way

Brand: The value of brands has changed. Historically, a strong brand worked as guide for the consumer and was formed by advertising it on mass media. Today, the main means to reach an audience are Google-search and social media, and the focus has shifted from big campaigns to targeted ads mimicking word-of-mouth recommendation

Compare the side-by-side of this Lancôme perfume ad from 2001 with its latest TikTok video ad (link here). In the latter, the logo is not even visible anymore. The brand wants to convey an image of authenticity instead of glamour. It wants to be your friend, not your guide

Predictability: As the world has become “flatter” with increased interconnectedness and plenty of capital available, challengers emerge faster. Together with the factors outlined above, the business world has become more unpredictable

So equities is the place to be for the long run, but it may not be the Warren Buffet formula anymore. What is it then? Let’s walk through some options:

First option, invest in real estate, via stocks/REITS or direct

On average, this is one of the lowest-risk forms of equity investments. Even with a potentially declining population, people will want to live in nice places, go on holiday, need to go to hospitals etc.

With government debt invalidated as traditional store of value, in many ways, real estate has taken on that role, a low return, safe and stable option to park money. This creates bubble risk, so handle with care (see last week’s post)

Second option, invest in regions that are still experiencing strong secular growth

The Western world is facing particular issues, but other regions are still more dynamic. And while many emerging market lack rule of law or are inaccessible (e.g., Mainland China), South-East Asia comes to mind as a strong-growth region with healthy dynamics

Third option, invest in businesses where the moat cannot be replaced by capital alone

Sometimes regulation protects incumbents. Examples are rating agencies (Moody’s, S&P), the North American railroad companies (Union Pacific, Canadian Pacific etc), Waste Management Inc. or Visa and Mastercard

In technology, network effects create moats where increased usage improves the product.3 Unsurprisingly, this leads us to the group of tech-megacaps known as FANGMAN (Facebook, Amazon, Netflix, Google, Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia)

While near-term overbought, with a ~3.5% earnings yield, FANGMAN stocks are comparatively cheap. The same yield is currently paid on BBB-debt, typically issued by companies of much inferior quality

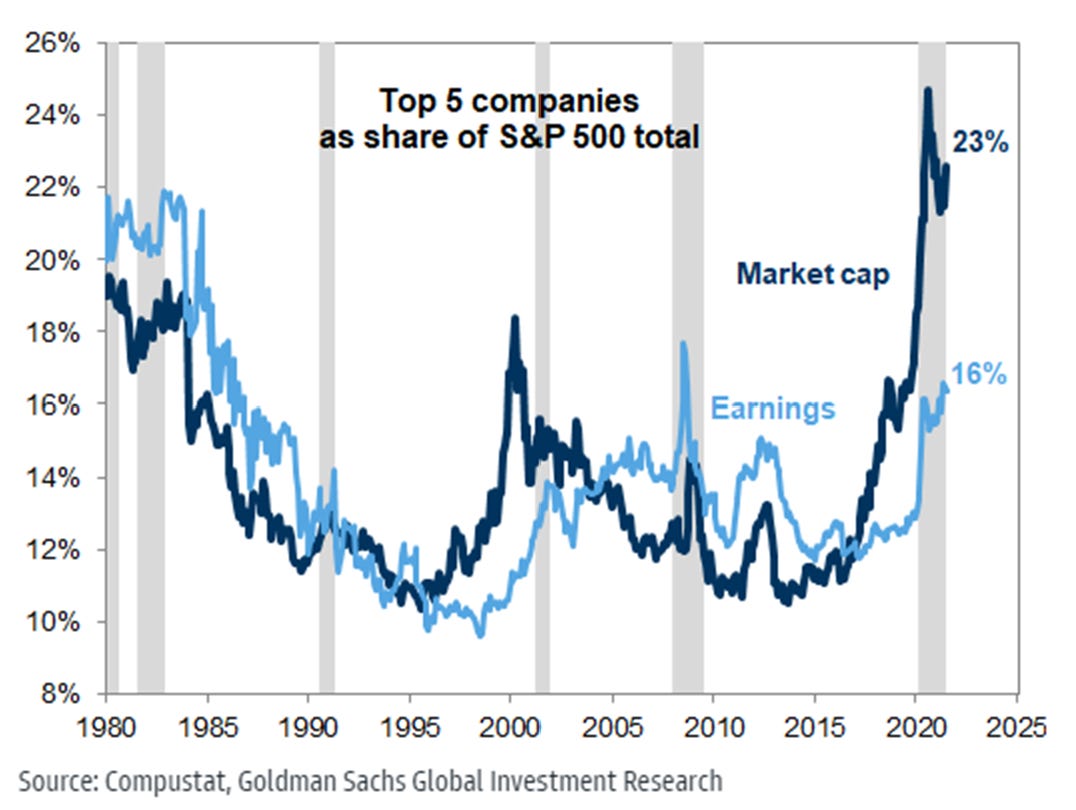

With the network effect in their sails, these companies have become so dominant that they command an unprecedent share of the market, as seen in the chart below:

With that in mind, the biggest threat to these businesses is regulation, as demonstrated by the current attacks by the Chinese government on the country’s tech sector

Fourth option, invest in high-growth tech (but not now). Over the long run, the technology sector is by far the best performing asset class. However, as it is so susceptible to boom and bust, timing matters immensely, as shown with the example of Cisco in last week’s post

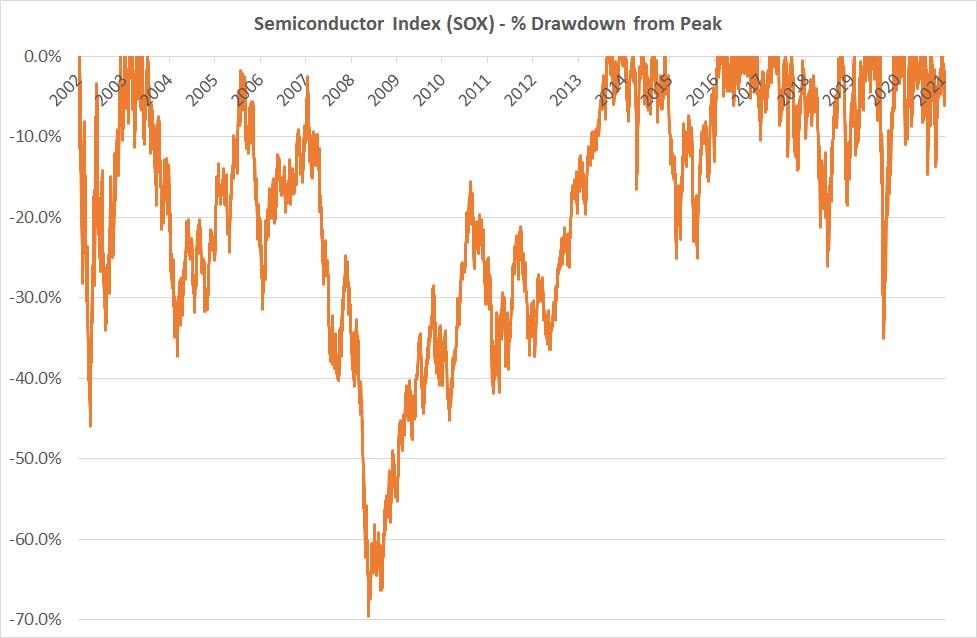

Given the sector’s volatility, this is not a problem. The ups- and downs will offer plenty of entry points, one just has to wait. Have a look at the peak-to-trough drawdowns in the Semiconductor index from 2002-2021, a period over which it went up 10x

Furthermore, coming back to Warren Buffet’s criterion of predictability, given how quickly the fortune of an individual tech company can change for better or worse, it seems better to invest in broader themes in order to dilute that risk

Some future megatrends in high-growth tech are as follows - with company tickers in brackets - the Metaverse (U, RBLX, FB), Mental Health (CMPS, ATAI, MNMD), the Knowledge Economy (DOCS, LAW, TWTR), Blockchain (ETH, SOL) or Big Data (PLTR, SNOW, PATH, NVDA). Wait for sell offs, buy them and then never look back

Fifth option, invest in businesses that do the capital allocation for you, and have done so successfully in the past

A good example are roll-ups in the software market, where thousands of small founder-led software companies occupy profitable niches. As succession questions kick-in, these are often acquired (i.e. “rolled-up”) by larger units

Constellation Software was the first to use said strategy and has grown from CAD$25m size in 1996 into a CAD$40bn giant. Smaller players in Europe (where the market is still much more fragmented) are Vitec, Topicus or Ideagen

Other companies to have demonstrated a strong track record in deploying capital in various ways are IAC, Transdigm, Autozone, Fairfax, SSNC, LVMH with its many successful luxury brand acquisitions, as well as Facebook with the acquisition of Whatsapp, Instagram and its current investments into VR and the Metaverse

Sixth option, create value-add in addition to your capital

As frequently discussed, central bank intervention has invalidated government debt as a haven for private investments. Consequently, trillions of dollars historically invested there are now looking for investment opportunities elsewhere

However, in a low-growth world, the number of good investment opportunities hasn’t gone up. Much more capital is chasing this limited number of opportunities

One way to create an edge in this race is to create additional value alongside one’s capital investment, e.g., in the form of openly published analysis and research, connectivity, or services alongside the investment

Conclusion: While traditional approaches for long-term investing may not be suitable for today’s economic context anymore, there are still plenty of other rewarding options for investors with a long view

My next post will address this topic in more detail

While immigration is still contributing to population growth in various Western countries, birth rates for all OECD countries except Israel and Mexico are <2 and declining. This is relevant as the domestic core demographic typically has much higher spending power

Google Search in particular is a good example of a moat that’s insurmountable with capital alone. Amazon tried for years and eventually gave up. Microsoft’s Bing after 20 years is still much inferior. As is the case with many AI applications - with every usage iteration the AI engine improves, and how to get to the same number of iterations with a less-good product?