Quantitative Frightening

Why the market is moving on from inflation to a bigger issue

A few months ago I wrote in “Emerging States of America” how high US public debt and high inflation are converging to create a combustible dynamic that is typical historically of Emerging Markets.

In recent weeks, this dynamic has become more pronounced. The Fed stepped up its Quantitative Tightening program to an unprecedented $95bn per month. At the same time, a currency crisis is brewing in Asia, diminishing the buying power of the largest US Treasury bond holders

Without Fed support and with lower foreign buying, US Treasury yields are untethered, and have to price-in the reality of 122% debt/GDP amidst structurally higher inflation. Higher bond yields are kryptonite for all other assets, so a liquidity crisis is shaping on the horizon, just as inflation cools off - for now

The Fed’s role is not enviable: Relent and risk inflation. Go too hard and the fragile system breaks. High leverage means no margin for error, so the job requires surgical precision. But the tools are, in the Fed’s own admission, blunt

This post walks through the challenges and what I see as the most likely outcome. As always, it concludes with a current outlook on markets

Global markets provide an ever-evolving set of datapoints, many of them I share actively on Twitter. When we connect these dots, a narrative emerges. This is what I see today:

To start, let’s review some recent inflation trends. More indicators point to a substantial cooling-off, something I had already highlighted in “From Hot to Cold in 90 Days”

Used Car prices, Airfares, ISM Survey Prices Paid, import prices, freight rates, average hourly earnings - all show sequential deceleration or even outright month-to-month price deflation

Of particular note: Rents, which are 33% of CPI, slowed in August. More downward pressure seems likely, as the housing bubble pops and unsold houses move to the rental market (NB: The CPI measures rents via the ~12 months lagging method OER-method, though markets typically see through that)

But most importantly, the Fed chose the right language to keep the inflation yo-yo down. Jerome Powell’s stern Jackson Hole speech left no opening for any dovish interpretation. Several Fed members reiterated the same message

As a result, the market’s 1-Year inflation expectations tanked to ~2%, the lowest since late 2020. But here’s what’s curious - US bond yields did not reflect any of it. They went up!

Yes, the long-term inflation outlook remains troubling (see “Is Inflation Over?”). But Powell was credible in Jackson Hole. Commodities sold off in response, there should have been some bond market reaction

So what is going on?

As I alluded to in the introduction, we are witnessing the first echoes of the paradoxical choice of either saving the financial system, or winning the fight against inflation. What do I mean by that?

In order to kill inflation, the Fed has to remove liquidity

In a highly levered world, there is only a very narrow path before this liquidity removal causes damage elsewhere

Hitting the narrow path requires surgical precision, but the Fed’s tools are blunt

In an interconnected global economy, damage may emerge in unsuspected areas (see more on Asian FX below)

Indeed, the Fed dials up the fight against inflation, and strains show up in the global financial system. For this, the US Treasury (UST) bond market is ground zero. Three dynamics are at play

First- Quantitative Tightening

Over the past 12 years, the Fed acquired ~$8tr Trillion of US government debt in a process described as Quantitative Easing “QE”.

This made the Fed the single biggest owner of US government debt and the biggest actor in the US Treasury bond market

The Fed recognised the inflation issue in late 2021. In response, it raised rates and decided to shrink its balance sheet by reversing QE via running-off its government debt holdings (= Quantitative Tightening "QT") The run-off started in June 2022 with $47.5bn per month1, to hit a maximum $95bn per month from September (now)2

Here is what’s important: No one actually knows the effects of QT, including the Fed’s economists. All we have is theoretical models and one limited historic example

The one historical example was very painful for markets. In early 2018, the Fed embarked on a similarly designed monthly QT program. A market crash followed later that year. This forced Jerome Powell to do a policy U-turn on interest rates. Later in 2019, dwindling bank-reserves caused the “Repo-crisis” which lead to the resumption of QE

Importantly, in 2018 global leverage was significantly lower, the full QT run-rate was $50bn, not $95bn, and inflation was low

Now, what is the likely effect of QT on markets? Rather than calculating a number, below is my attempt at a common sense answer. For that I turn once again to the US Treasury market:

The Fed is the largest actor in the Treasury market, it owns 24% of all debt issued. This actor retreating will leave a big hole

The Fed is an price-insensitive buyer, it is oblivious to fundamentals (e.g. risk of default, risk of inflation > interest rate). Thus, it likely suppressed yields considerably

The Fed’s outsize role in the US Treasury market has likely given confidence to other market participants

Finally, the global debt debt pile relies on a stable or growing Fed balance sheet providing USD liquidity to the world. Instead, it is now shrinking

Summary: Looking at the historic precedent as well as some common sense deductions, QT will likely be a significant challenge for Treasury markets. Treasuries provide markets with its “risk-free rate”, therefore this challenge extends to all other assets classes

Second- Asian Currency Turmoil

In Jackson Hole, G7 central banks gave a unified message, with one exception - the Bank of Japan. It remains dovish

There was Jerome Powell’s hawkish speech. The ECB’s Isabel Schnabel laid out in painstaking detail why we’d face higher inflation for longer. The BOJ’s Haruhiko Kuroda said - nothing

In Jackson Hole’s wake, US and European rates increased. Japan’s rates stayed steady, the BOJ caps them in a process called Yield Curve Control (e.g. 10-year yield fixed to 0.25%)

Accordingly, the yield differential between Japan and the US/Europe grew. So something else has to give - the Yen. It has depreciated 22% against the US Dollar since the beginning of the year, while traditionally a safe haven in turbulent times

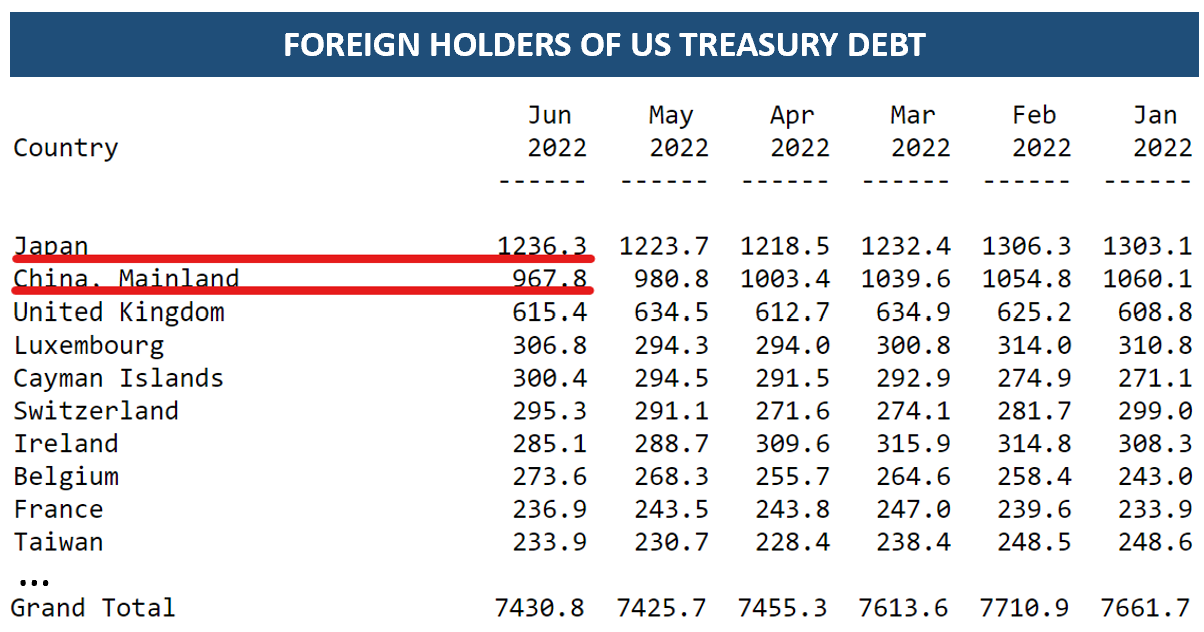

But why does that matter for our purposes? Simple - foreigners own ~30% of all debt issued, and Japan is this group’s biggest holder

And with a weaker Yen, Japan’s purchasing power to buy USTs is greatly diminished

Which is visible in the market’s now most important correlation - between the Yen and long term US Treasury Yields

What’s more, Japan is China’s biggest competitor for global exports. A lower Yen increases pressure on China to also devalue its currency

You might have noticed that China is the second biggest foreign holder of USTs

In addition to Japan, other dynamics strain China’s Renminbi, which is fixed. China has to cope with capital flight as domestic investors lose faith amidst zero-Covid and a bursting property bubble

Coming back to Japan, let’s look at its government budget: Half of income is from selling debt, one quarter of expenses goes to servicing said debt

No need to spell out what higher rates would mean for Japan’s 230% debt/GDP mountain, even if they only materialise over time3

So in my view, Japan does not have much choice other than letting the Yen depreciate

Similar dynamics are at play in Europe and the UK (though to a lesser degree relevant for the US Treasury market as these countries are smaller holders)

What do all these countries have in common? Too much debt, which stands in the way of setting interest rates high enough to combat inflation. As a result, their currencies depreciate against the US Dollar

Ironically, the Fed’s $8Tr Quantitative Easing purchases provided foreign markets with the liquidity to lever up without currency depreciation. Now the Fed tightens and this dynamic reverses, amplified by the fact that the world is short US Dollars via trade finance FX and foreign dollar-denominated debt4

Summary: Weaker foreign currencies, in particular in Asia, reduce foreign demand for US Treasuries. Foreigners are the second biggest group of US government debt owners after the Fed

Third- US Treasury Issuance

The Fed and foreign buyers both sit on the demand side for USTs. For a complete picture, it composes as follows:

It is important to note that US domestic banks are near maxed out on their treasury holdings and would require regulatory reform to increase them. Banks hold ~6% of all debt issued

Naturally, the supply side is equally relevant:

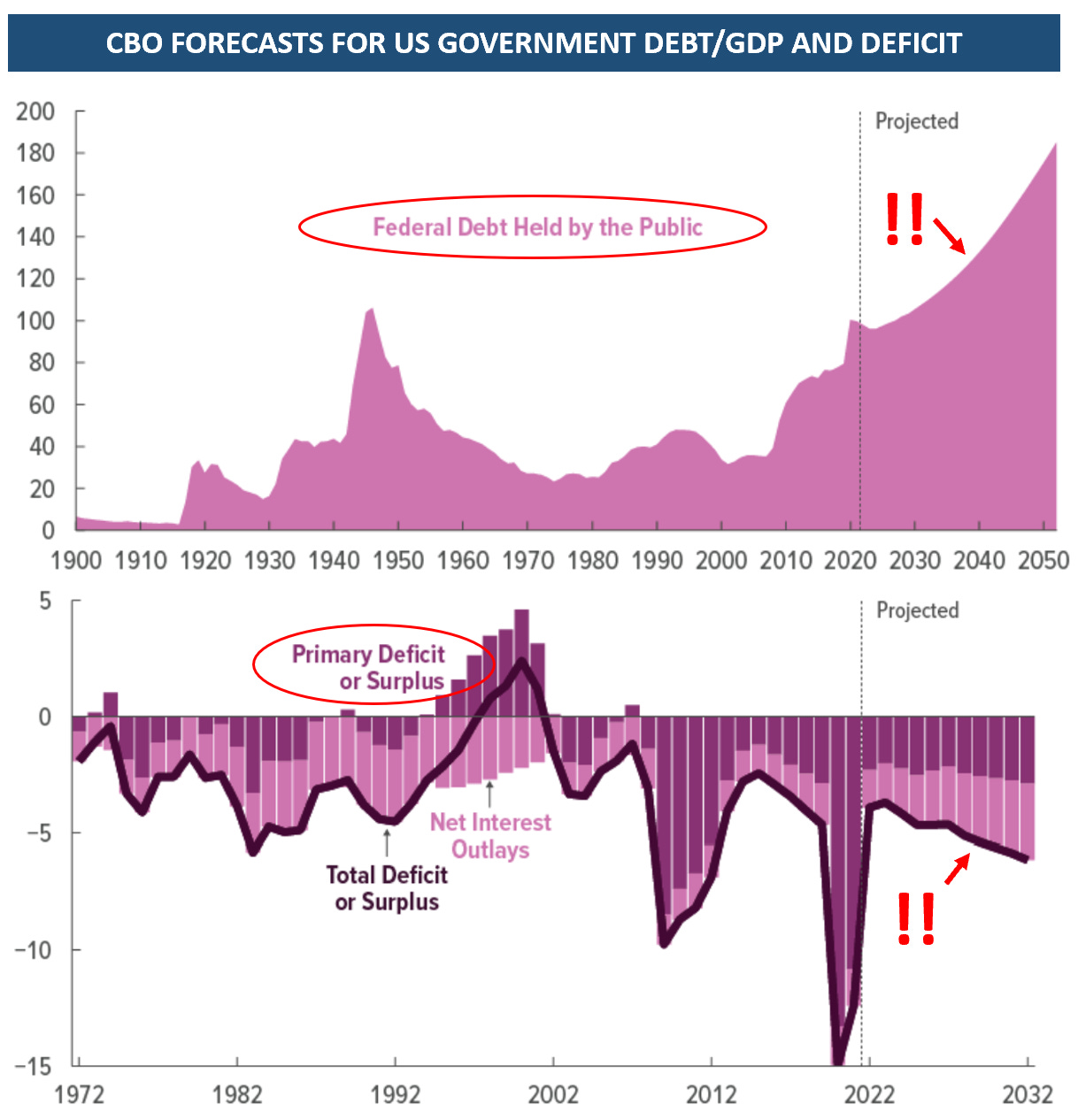

Earlier in the year, high inflation and high asset prices boosted nominal US Treasury tax income. As inflation comes down and the stock market declines, tax revenues decline

California and New York are lead indicators and particularly sensitive to market swings

As a consequence, the Treasury has to issue more debt than planned

Summary: More UST issuance simply means more supply that needs to be bought

Let’s summarise this point:

Due to QT, the Fed will buy much less US Treasury debt

Due to weak FX, Foreigners will buy less

Due to regulation, Banks are maxed out

Due to lower tax revenues, the treasury will issue more

Without the Fed, lower foreign demand and no bank demand, US Treasury bonds are now freely exposed to the private sector’s market pricing mechanism

So, I would like to ask you, how likely are you to buy a US 10-Year bond at 3.2% yield, with US debt/GDP at 120%, in a world of likely structurally higher inflation?

Indeed, without a backstop, it does not seem like a great investment. But as long as US Treasuries remain untethered, we have the following feedback loops at play:

Stronger US Dollar → lower foreign UST demand → higher UST yields → stronger US Dollar

Weaker Euro/GBP/Yen → lower real wages → more debt-financed government spending → weaker Euro/GBP/Yen

Weaker asset markets → weaker consumer confidence → weaker economy → weaker asset markets

In a healthy financial system, buyers would eventually step in to break these loops. In an unhealthy system the loops run their course until something crashes - or, of course, until the buyer of last resort steps in once again:

Conclusion: Markets are now likely in several negative feedback loops with US Treasuries as ground zero. My central scenario is this feedback loop requires intervention to be broken

The likely reality is that there is simply too much global debt for markets to stand on their own feet

NB: This wasn’t a problem as long as inflation and thus interest rates were low. At 0% rates, the theoretical debt capacity is infinite

With this in mind, similarly to 2018, I expect markets to keep drifting down and eventually panic

Then, I think the Fed will eventually have to chose between letting the financial system crash, or intervene. I think it will chose the latter and pick one of the following immediate options:

Allow banks to hold more Treasuries via a reform of the SLR

Lower the rate paid on the Reverse Repo facility (RRP), or cap its size. The RRP is essentially an off-balance sheet vehicle created by the Fed to absorb the excessive amounts of QE provided in 2021, with a money multiplier of zero. It currently holds $2.2tr liquidity, incentivised to stay there by a sufficiently high interest rate and insufficient bank deposit capacity

The treasury conducts buybacks that increase the amount of bills in circulation. A higher stock of bills allows liquidity to move from the RRP into banks

All these measures have in common that they are closet varieties of Quantitative Easing, as they provide liquidity to financial markets. So here we are, back at the central issue for today’s Western economies:

In the past twenty years, all QE-style bailouts were seemingly consequence-free. Inflation was low, and globalisation ensured it stayed that way

Today, the world’s economic structure has changed. The demographic cliff, deglobalisation and lower immigration are, in my view, all inflationary

Similarly, commodity supplies are challenged and capex has been lagging demand by a wide margin

If the Fed once more bails markets out, can it do so without bringing back inflation?

This depends on the size of the liquidity injections, whether it is SLR/RRP/QT or buyback related, and on the depth of the preceding hole

Either way, in my view, in that moment, all hard assets are bid frantically, so at the very least a near-term inflationary surge seem likely

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting the dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

Europe - Just over the last few days, the Finish economic minister declared a Lehman moment in Nordic power markets, and the Scandinavian countries announced a €33bn bailout. The UK’s Centrica is in talks for a multi-billion bailout, as is Swiss utility Axpo. Last week, more than 70k people demonstrated in Prague against rising prices

As I had written last week, without intervention Europe would face the abyss, with the example of the UK household energy bill bound to reach an impossible £6k on £31k average household income. I had predicted that governments would provide subsidies funded by more debt issuance rather than revenue neutral, which would likely be inflationary. This morning newly inaugurated UK PM Liz Truss announced a £130bn (5% GDP) support mechanism that caps household energy bills at £2k (2x 2021), funded by debt, while insisting on tax cuts she promised during her leadership campaign. Germany announced €65bn support measures, here in part funded by excess utility earnings

The various schemes announced over the last few days rightly reduce the burden on the consumer and support aggregate income. Here is what’s important: Europe is short energy. And there lies the difference to the ‘08 Financial Crisis/Lehman Brothers comparisons. You can print money to cover Lehman’s losses, but you cannot “print” energy. If consumers stop saving energy, the burden moves to the corporate sector. Subsidies or not, corporates need energy to produce. 60% of UK manufacturers are at risk of going out of business without support. Hakle in Germany, one of the world’s oldest toilet paper manufacturers, just declared bankruptcy due to excessive energy prices. Expect more to come

Please note, rather than being bullish or bearish, I follow data. In 2020, that lead me to believe early on that the economy would recover, and that the vaccine would provide relief. This time the data tells me it is bad. There is still much downside in European corporate earnings, and as such, in European equities

Bonds - In line with the reasoning of this post, I find it likely that US long-term yields have not seen their highs. However, the pace of events is hard to predict. If any of the outlined dynamics escalate, bonds would benefit from a save haven bid as everything else is sold. In 2018 bond yields first rose and then fell when the market crashed. This is why I continue to believe that the best horse to express these views is to short equities, rather than short bonds. Equities decline if bond yields rise. They also decline if events accelerate into a broader fallout, in which bonds would get a save haven bid

Oil - the liquidity crunch is bad for all assets, in my view. As such, I am closing my oil position at around cost. In particular the stress in Asian currencies could lead to further local demand reduction, which may temporarily outweigh the supportive drivers I outlined before. However, keep in mind commodity supply likely remains tight and in any Fed turnaround these will be heavily bid

The path I expect is further market turbulence that eventually forces the Fed to pause, and apply some of the relief measures outlined above. I am waiting for that moment to deploy capital on the long side

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!

For technical reasons related to MBS settlement, the Fed balance sheet actually only shrunk $135bn since its peak in March. So September will be the first month where the full effect unfolds

To be precise, the current QT program ($60bn USTs + $35bn MBS) only lets debt up to said amount expire, rather than recycle the matured amount into new bills and bonds, which would hold the Fed balance sheet steady. Due to higher rates mortgage refinancing has come to a standstill, which lead to the suggestion e.g. by the Atlanta Fed’s [Ralph Bostic] to actively sell MBS to reach the full $35bn of mortgage QT. If more than $95bn Fed holdings mature in any given months, the Fed will still buy new bills and bonds for these, so it has not gone entirely inactive

Even if they’d only gradually materialise over time, as old debt is refinanced with new

As always, excellent piece! Do you expect any of these Fed moves to manifest in Sept?

This article could have been titled, "zugswang".