Rhyme or Repeat?

Some stunning historical parallels, and what mistake from the 1970s is about to be repeated

First, on Ukraine, talks in Turkey seem like an important step forward. As discussed before, the driver behind any rapprochement is likely the Russian army’s exhaustion, while Ukraine is taking back territory. I first highlighted the possibility of a ceasefire on March 8 and markets have gone up in a straight line since. However, this is not over. Russia’s credibility is near zero after repeated lies and humanitarian violations. Please continue to donate, e.g. to Unicef Ukraine

Taking a broader look at the current economic landscape, there are two tools at one’s disposal with which to attempt any predictions: the application of common sense, and the study of history. With regards to the latter, the assumption is that human behavior doesn’t change, so historical parallels can prove instructive. For today’s context, the period of 1965-1983 appears to provide some stunning similarities

This post contrasts back then and today. It also highlights a serious mistake that’s about to be repeated, and as usual draws conclusions for markets and the economy

The period of 1965-1983 was shaped by high inflation and frequent conflicts. Framed by the Vietnam War on one end and Ronald Reagan’s presidency at the other, it provides ample resource for comparison. Let’s dive in:

To start, the political mood back then and today was shaped by a desire to avoid previous mistakes

In 1960s, the Great Depression was still on everyone’s minds. Dramatic monetary policy mistakes aggravated the economic fallout in the 1930s, so afterwards, Central Banks added maximum employment as policy goal, alongside price stability1. Governments spent big in support, such as L. B. Johnson’s Great Society program

Today, similarly, after decades of secular stagnation, low real wage growth and rising inequality, an increased focus on social issues has penetrated monetary policy. In 2020, the Fed elevated inclusive and minority employment goals into its agenda, and government spending increased dramatically

This political mood coincided with a national emergency

In the late 1960s, the US’s involvement in Vietnam turned into a full-blown war. The war provided the pretext to keep spending, despite an increase in inflation

In 2020, COVID-19 provided the pretext to override any expenditure restraint, and trillions of dollars were pumped into the economy

In both instances, high inflation ensued, most visible in commodity prices. This emboldened bad commodity-rich actors to aggressive acts, which in turn furthered inflation

In 1973, a coalition of Arab states attacked Israel in what came to be known as Yom-Kippur war. The war was followed by a 5-month long oil embargo of the oil-rich Arab nations by Israel’s supporters. It caused a 300% increase in the oil price

Similarly, Russia’s attack on Ukraine coincided with historically high European gas prices; Russia actively uses gas supplies as a threat

Amidst high commodity prices and a weak Central Bank response, inflation became embedded in public assumptions

In the early 1970s, after a few years of elevated inflation, households incorporated expectations of high inflation into their behavior. Expenditure was brought forward and wages were linked to inflation (“COLAs”). All this created more inflation

Today, as Central Banks have waited too long to take serious action, inflation expectation are again on the way up: UK inflation expectation for the next 5-10 years rose to 4.4% in March (!), US-5 year inflation expectations (“breakevens”) are now at 3.7%:

High inflation times are high tax times. With more demand than supply, the economic damage of higher taxes seems much more limited

In the 1970s UK, the marginal income tax rate was 83%, in the US 70%

This past week, the US-government introduced new tax legislation. It’s unclear what will make it through the Senate, but the direction is up

Back then and today, the government asked the public to cut back on energy consumption

In a famous televised speech in 1977, US-President Jimmy Carter faced the camera wearing a cardigan to keep warm and suggested everyone turn down their thermostats. In Western Europe, governments banned driving on Sundays

Today, similar measures have been suggested by the IEA or French minister Bruno le Maire. Last week, Tokyo asked its residents to shut off lights to avoid a power outage

Ok, but what about the part of repeating past mistakes? Let’s turn to that now:

Inflation represents the economic issue of too much demand for a given amount of supply. It’s the proverbial “too much money around”. This solves via price increases until enough demand is “destroyed” and demand and supply are in balance again

For a lot of people, this is a very painful process. Bills on everyday-items like food or energy go up considerably, which is unsettling and unfair (e.g. the average UK energy bill on 1st April increases from ~£1300 to £2000 p.a.)

What could the government seemingly do to help with higher prices? Subsidies come to mind, to alleviate the pain from higher prices

And this is exactly what we are seeing right now, an onslaught of subsidies, tax breaks and other supportive government payments, typically financed by debt. Examples include Germany, Spain, Japan, the UK or regions like Quebec. From there, this local headline is telling:

The journalist unwittingly describes the paradox: “Government prints money to fight inflation, having caused inflation with printed money”

More so, many of these programs don’t have any, or very high social caps. Instead, they are blanket per citizen/litre of fuel subsidy. A large part of the benefit goes to people who really don’t need it

California seems to be particularly bad, with a $400 cheque per car. Does Jay Leno in Beverly Hills really need 180 $400 cheques? (Yes, he indeed owns 180 cars… Not every ones does, but you get my point). In my view, the $11bn total cost would much better be spent on its schools or public infrastructure, where society would benefit for decades

These government efforts lead us straight to the core of why inflation was so bad and lingered around for so long in the 1970s

Back then, Central Banks waited too long to reign in inflation. The result was a disorderly evolution of the issue - commonly called stagflation

In stagflation, prices for some goods rise so much that they become unaffordable for large parts of the population. Significant cut-backs have to be made elsewhere to continue to afford them (e.g., high energy bills force cut backs in discretionary consumption)

The reduced demand for discretionary goods increases unemployment in those sectors. The result is both inflation and unemployment

So in the 1970s, when unemployment increased, governments and Central Banks had two problems on their hands, inflation and unemployment. They had to pick a fight

And they chose to fight unemployment. The US government ran large deficits, e.g., to subside high industrial energy costs, and the Fed kept rates low to finance these deficits, all the while inflation was still raging

But what happens if you create more new money (= run deficits), when the supply of goods and services is already maxed out? All you achieve is more inflation

It was the wrong fight, and it extended the problem for years, until Paul Volcker changed course in 1980

Ok, so we’re repeating the same mistake again? Yes and no

While Paul Volcker has often been credited with ending inflation and his predecessor Arthur Burns vilified for letting it run so long, one has to note that either just followed public opinion2

Public opinion only strongly turned against inflation towards the late 1970s. Volcker also picked the inflation fight because it became popular

Today, in the US, public opinion is very much in favor of fighting inflation. It’s seen as the number one economic issue. As a consequence, the Federal government does not participate in the subsidy-fest, and Fed Chair Jerome Powell positions himself in the shoes of Paul Volcker (see last post)

This is in contrast to Europe, where other issues are more prominent and governments still live the context of the past decade - deficit spending, financed by low interest rates

Summary: History doesn’t repeat, but it rhymes. The 1970s show unpleasant parallels, but the US at least seems to come around to its lessons. For Europe, for now, the conclusion seems different

However - yes, US public opinion is firmly behind the inflation fight, but what if unemployment rises?

The hugely challenging issue is that for entrenched inflation to cool off, demand needs to be reduced. In other words, household income needs to stall or shrink

There are two avenues to this: (1) falling asset prices and (2) rising unemployment. Neither is particularly appealing. Unemployment is the much more powerful lever, but unemployment is awful. Here it’s just a word, but for anyone affected it can represent a life disaster

When Paul Volcker brought inflation down in the early 1980s, it took a two-year long recession, and unemployment rose much higher than during the financial crisis

Please keep in mind, as the economy works on cyclical momentum, the Fed is unlikely to be able to engineer “a bit of unemployment”. Over the past 75 years, every time the unemployment rate has moved up by 0.5%, a full-blown recession has occurred3

What does this mean for markets?

Equity markets, in particular US-Tech, staged an impressive rally since the March lows. Before going into detail on a few sub-sectors, let me point out the following

First, let’s make no mistake, inflation continues to rage and all signs point to an acceleration. 4.4m Americans quit their jobs in February, a record high, March rent data is up again, house prices are up, the CPIs for Spain and North-Rhine Westphalia came in today at a stunning 9.8% and 7.6% y-o-y. There is no economic slowdown as Paul Krugman suggests in the NYT. Instead, US data is accelerating (e.g., March flash PMIs) and the housing market remains on fire, with zero effect so far from higher mortgage rates. All this while real rates remain negative (see last post)

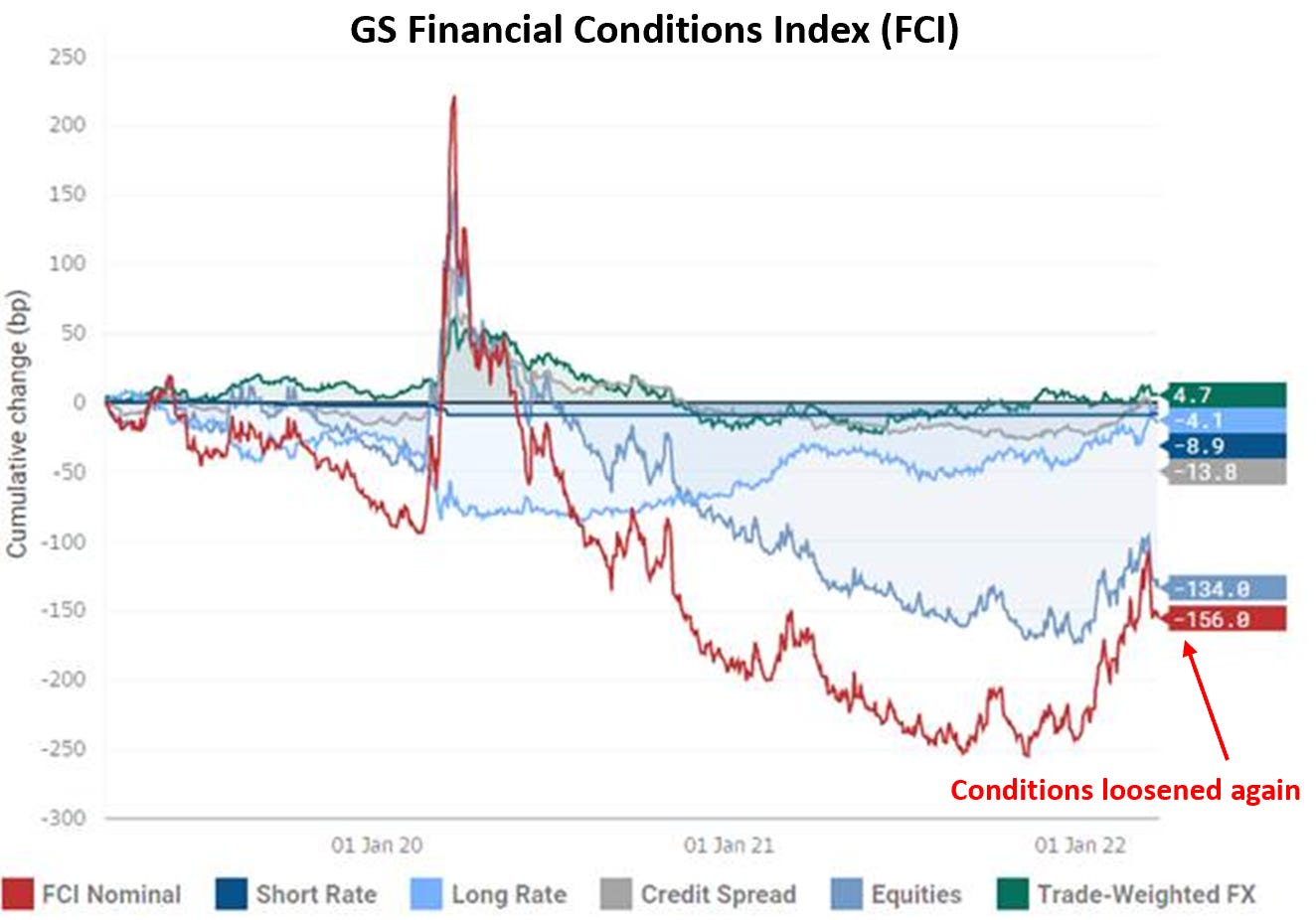

Interest rates are not the only metric that influence inflation. Economic activity is shaped by a broader set of metrics that can be summarised as “financial conditions”. Equity markets form a major part of that4

Yes, interest rates have moved up recently, but stocks have also shot up, so financial conditions actually loosened (!), as can be seen in the chart below:

The recent rally in equity market significantly complicates the Fed’s task to bring down inflation, despite the recent rise in interest rates. In fact, it is in itself a manifestation of excess household liquidity looking for a home. It’s telling that retail favorites such as Tesla or “meme stocks” Gamestop and AMC lead the move

I had mentioned common sense in the introduction

While one has to accept that the future is uncertain and many outcomes are possible, the conclusion seems obvious here - Equity markets are challenging the Fed in its quest to bring down inflation. The Fed has the tools to respond. Expect it to use them

Turning to individual sectors

Nasdaq-100: Having turned constructive early March amid excessive bearishness, last week I had highlighted my belief that the rally in US-Tech is closer to its end than its beginning. While I certainly won’t pretend to be able to predict every turn, I just want to stress that with every additional % up in US stocks, the Fed is more provoked to respond. According to PB data from MS, most shorts that have been set over the past 6 weeks have been covered again, so now the risk/reward seems firmly down. Either way, in order to makes sense of current levels, you need to believe that inflation will be tamed with ~2.5% long-terms rates5. I’ve outlined last week why I find that unlikely.

DAX: I had favored this on March 8th with a view on Ukraine. However, after a 15% move, a resolution to the war is largely priced in. Irrespectively, Europe is firmly on the way to stagflation, and just like in the 1970s, when the oil price stayed high after the oil embargo, it seems likely that commodity prices remain elevated even if Russia returns to global markets, as demand/supply balances were already challenged before the conflict. This is bad for European industrials and the European consumer, and the risk/reward now seems down

Oil Services: COVID-19 outbreaks in China might cause temporary obstacles, but the structural drivers of energy security, underinvestment and unabated demand remain in full force

Trucking: Above, I had laid out how high energy prices force a reshuffling of consumer expenditure. This is visible in near-term car sales data where less affluent buyers leave the market, or Apple’s Q2 production forecast. Together with a re-open driven shift to services (think holidays over handbags), this is negative for the super-cyclical trucking industry, which ships durable goods and has added 170k new trucks in the US since 2020

ADDENDUM:

Given much of this post is about the 1970s, here’s an overview of how the different asset classes fared back then

Please keep in mind that this is not a suggestion that the same would be repeated, history rhymes but does not repeat

Either way, in an inflationary environment the best investments combine pricing power with low valuation - sounds like a unicorn, but I am sure some good midcap/small cap specialists will be able to find them!

It took another 20 years for Central Banks to attain the power to act on these goals. Their moment came when Nixon left the gold standard in 1971

In this 1979 speech Arthur Burns details how political opinion prevented him from acting more forcefully against inflation

They are, in turn, of course also influenced by interest rates

Alternatively, you might also believe that the Fed remains behind the curve on inflation and rates stay low for that reason. However, that would likely lead to a stagflationary outcome (=earnings down) and/or a more forceful reaction later on