Steinbeck, Physics and Purchasing Managers

What I've learnt over 15 years in public markets (Part I)

I am often asked what stocks or investments I would recommend. This is a tricky question, as just giving a name without the corresponding thought framework isn’t very helpful. I’ve therefore put together this small series that introduces how I think about investments. It’s the synthesis of my experience in public markets over the past 15 years, but hopefully useful beyond that context. Today’s post lays out the simple underlying principle and applies it to broad equity markets. Two subsequent posts will describe its application for short-term as well as long-term investments

While the principle may be very simple, I want to explain in a few short steps how to get there. For that, let’s start with a few quotes from the world of literature. In his 1920s biblically-inspired novel “East of Eden,” John Steinbeck writes in a central passage:

“A child may ask, “What’s the world’s story about"? […] Humans are caught, in their lives, in their thoughts, in their hungers and ambitions, in a net of good and evil. This is the only story we have and it occurs on all levels of feeling and intelligence. Virtue and vice were warp and woof of our first consciousness, and they will be the fabric of our last. There is no other story” (413, The Viking Press, 1952)

A few years later Hermann Hesse writes in his coming-of-age story of the two friends Narcissus and Goldmund:

“All existence seemed to be based on duality, on contrast. Either one was a man or a woman, either a wanderer or a sedentary, a thinking person or a feeling person [.] One always had to pay for the one with the loss of the other, and one thing was always just as desirable as the other” (249, Picador, 1968)

And the psychologist Carl Jung famously quipped:

“The pendulum of the mind alternates between sense and nonsense, not between right and wrong”

What are these quotes describing, what do they have in common?

They all describe the quintessential human condition, a field of tension between two opposing poles, and the inability to maintain a perfect balance between them

We are all familiar with this struggle in our everyday lives, trying to find a perfect equilibrium between our ambitions and desires for family, health, and work, which often might find themselves at odds with another

However, we’re unable to maintain such equilibrium as the world is dynamic and constantly changing. So we find ourselves oscillating between poles, constantly re-adjusting in order to keep balance

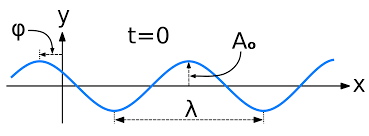

This principle is not only essential human nature, it is in fact everywhere in nature. The building blocks of our world are resting on it

The smallest known particles and their behaviour are illustrated by the wave-function at the core of quantum physics. It describes the probability of finding an ever-moving electron particle at a certain place in space and time, first expressed by Erwin Schroedinger in 1925

Equally, with the universe ever expanding since the Big Bang, everything is subject to constant motion and corresponding change, making it hard to maintain balance in a state of flux

Ok, interesting, but what does all of this have to do with investing?

Capital markets are a human-made construct that is nothing else but the sum and the reflection of millions of humans, their thoughts and emotions, how they act and how they think

And because we are all made of a similar fabric, these individual thoughts and actions don’t cancel each other out, rather they appear in synchrony

Accordingly, the pendulum-like wave-function pattern can be found everywhere in data related to capital markets, from intraday price moves that market-maker businesses are built on to multi-decade economic cycles1

These waves shape around trends that can be upwards sloping (e.g., technology), downwards sloping (e.g., commodities) or just sideways

As a rule of thumb, the steeper the trend, the more extreme the oscillations around it

The constant ebb and flow, pull and give, hype and panic, in other words, the wave-function pattern, to me, is the most important learning and what this framework is based on

So let’s apply it in practice, looking at how this pendulum is expressed in equity markets

Equity markets are the aggregate of thousands of companies listed on the stock market, which again are a direct reflection of economic activity

There are literally hundreds of metrics measuring economic activity and a seemingly equal number of commentators providing “colour” on those. Big and complex models are being built, trying to precisely forecast the future, often with disappointing results

In an ocean of noise, it pays to keep things simple

In fact, you only need to follow one metric to know where we stand in the cycle of economic activity. This is the Purchasing Manager Index (PMI), in particular for Manufacturing Industries. It’s simple, broad and forward-looking. Here is the US Manufacturing PMI over the past thirty years:

A couple of observations:

The PMI is a survey of a representative set of Purchasing Managers in all sorts of companies, asking them “How much do you intend to buy next month?”. It’s provided for free by research firms Markit and ISM at the beginning of every month

Purchasing Managers are responsible for acquiring the products necessary for production. For example, at a company producing cars, the Purchasing Manager will order the steel, bolts, batteries etc. necessary to produce the car. Accordingly, they have a real-time view of the state of demand

Even though a large part of the economy today is service-related, it still makes sense to focus on manufacturing PMIs. The reason is that manufacturing is the beating heart of the economy

Many services are in fact a by-product of manufacturing activities. Think of the advertising agency creating an ad for a new car, the software company helping the car maker lower its operating costs, the insurance company selling insurance for a new car etc.

The pendulum-like wave pattern is clearly visible in PMIs, why is it there?

Again, economic activity is nothing but a reflection of us humans acting together. It reflects an oscillation between the human emotions of greed and fear, of confidence and anxiety.

When times are euphoric and PMIs peak, confidence is omnipresent, money is plentiful and caution is low. Accordingly, the decisions made during that period are often less well thought-through

Keeping with the PMIs, Purchasing Managers may order too many input products. In broader terms, executives may decide to build too big a new factory or overpay for an acquisition

The “graveyard” of poor top-of-the-cycle decisions is long and wide, ranging from TimeWarner’s acquisition of AOL to ThyssenKrupp’s gigantic steel plant projects in Brazil. Or what about $20bn market cap for a company with a fake automotive product rolling down a hill? (I had written on the current high risk of capital mis-allocation in tech previously here)

These poor decisions express themselves in lower growth going forward, and as economic growth slows down, nervousness increases and decision-making becomes more careful

As the pendulum now swings back, only the best projects receive funding, and from them robust growth develops forward. The cycle begins again

This is amplified by the fact that we are herd animals and look to our peers and neighbors when making decisions, creating a mutually-reinforcing feedback loop

Ok great, but what does that mean for the markets, do I buy or sell?

Below is the same PMI chart as above, with the year-on-year returns of the S&P 500 added2. Again, the wave-like pattern is clearly visible, and there is a very close correlation between the two metrics

It’s clearly visible that equity market returns (with the S&P 500 as proxy) are significantly stronger when PMIs are rising, and significantly weaker when PMIs are falling

As an investor, it’s simple and obvious how to use this relationship in equity markets. There is nothing more to it. When PMIs are low it’s the time to deploy capital. When they are high, it’s time to harvest or be careful

More so, all market “blow ups” have occurred in the descending arm of the PMI curve, e.g., spring 2000, fall 2008, summer 2011, beginning 2016, late 2018 and the Covid-19 related sell-off in March 2020

Conclusion: Capital markets are a reflection of human nature, with the corresponding ebb and flow between two poles, or between “sense and nonsense” as Carl Jung would say. While every day we are bombarded with an endless amount of information, one can cut out the noise and it only requires a few simple steps to recognise where we stand between those poles. Applying these findings to equity markets:

As an investor in equity markets one should be firing on all cylinders when PMIs are LOW, and one should be very careful with one’s money when everyone’s euphoric and PMIs are HIGH

Right now, as is evident from the charts, we are in the euphoric part. PMIs have likely peaked, and will eventually go down from here. That doesn’t mean that the stock market will collapse tomorrow, but the period of strong returns is behind us

This has been the introduction of the basic principle of the wave-function in broad equity markets. The next two posts will elaborate on its application in short-term and long-term decisions

Addendum - a brief word on interest rates

I had written in prior posts about the role of interest rates, how in every economic slowdown (= PMIs going down) governments had responded with lowering interest rates, and how that lead to an increase in debt that made it impossible to bring interest rates back up again after the economy recovered (= PMIs going up)

Bringing these pieces together, in the below chart the 30-year interest rate on US government debt is added to the PMI. Again the wave-like pattern and correlation of both metrics is visible3

Given the high levels of debt, ever lower rates and intervention were needed to re-ignite the PMI cycle to the upside. Letting the cycle run its natural course without intervention would have created a healthy cleansing of the economy, but at a terrible cost of high unemployment and instability

As an example, in a somewhat shocking statistic, the US economy managed to generate the same real GDP in the first quarter of 2021 as before the COVID-19 shock (first quarter of 2020), with 8.5m fewer people employed

Without government and central bank intervention, many more people would have been unemployed for a much longer time frame

The trillion-dollar question will be, when the pendulum swings back again from the current euphoric state into something more tempered, how will the economy be pushed forward into the upswing again

Cf. Bridgewater’s Ray Dalio’s work on long-term debt cycle or Kondratieff’s super cycles

Year-on-Year, 3-months average to smoothen curve

With its long duration, the 30-year interest rate is a proxy of what investors think will be the long-term economic growth potential, beyond whatever state the economy is in today