As discussed in previous posts, we are in the middle of an economic regime change. The past decades were shaped by globalisation, which brought much wealth to billions of people in emerging markets. In turn, Western economies saw anaemic growth and rising inequality. This lead to tensions and a political reaction. First gradually, with the re-emergence of barriers to trade and immigration, then suddenly, with the exorbitant COVID-19 stimulus that decisively ended the weak-demand morass

The past decade also saw the introduction of investor policies to address climate change and rapidly rising carbon emissions, commonly summarised as ESG. Chosen in good faith at the time, they unfold differently in this new economic regime. In fact, they present a social time bomb. ESG-driven underinvestment in carbon-intensive natural resources meets demand that’s not only unchanged, but now much stronger, with the balancing mechanism higher prices for gasoline, power, food etc. This is equivalent to a regressive tax on lower-income groups, who are overproportionally affected

This post walks through the current dynamics for commodities and ESG, and weaves the conclusions into previously introduced views around markets, the Fed and inflation

While the corporate world has historically been slow to acknowledge its role in climate change, the rise in global temperature became too much to ignore…

…and a broad consensus emerged to lower carbon emissions, the prime culprit for global warming

In particular, natural resources corporations were pressured to lower their emissions. Measures were introduced on a societal level, such as the legally binding EU 2050 net-zero target, or the pivotal court decision addressing oil-giant Royal Dutch Shell

Many investors joined the effort. They reorganised their charters to focus only on companies that fulfil certain environmental, social and governance standards (=ESG)

Due to their high carbon emissions, this would typically exclude oil & gas and mining companies

With their compelling allure, ESG-compliant investment funds became hugely popular, growing to >$35 trillion AUM in 2021

The re-allocation continues to this day, e.g. New York state’s pension fund and Danish AkademikerPension just dumped their oil & gas holdings

Everyone follows incentives, so in order to keep investors and improve their share prices, resources companies reigned in exploration and production growth

Let’s look at oil capex as an example. It declined to the lowest level in 20 years, despite the current high oil price

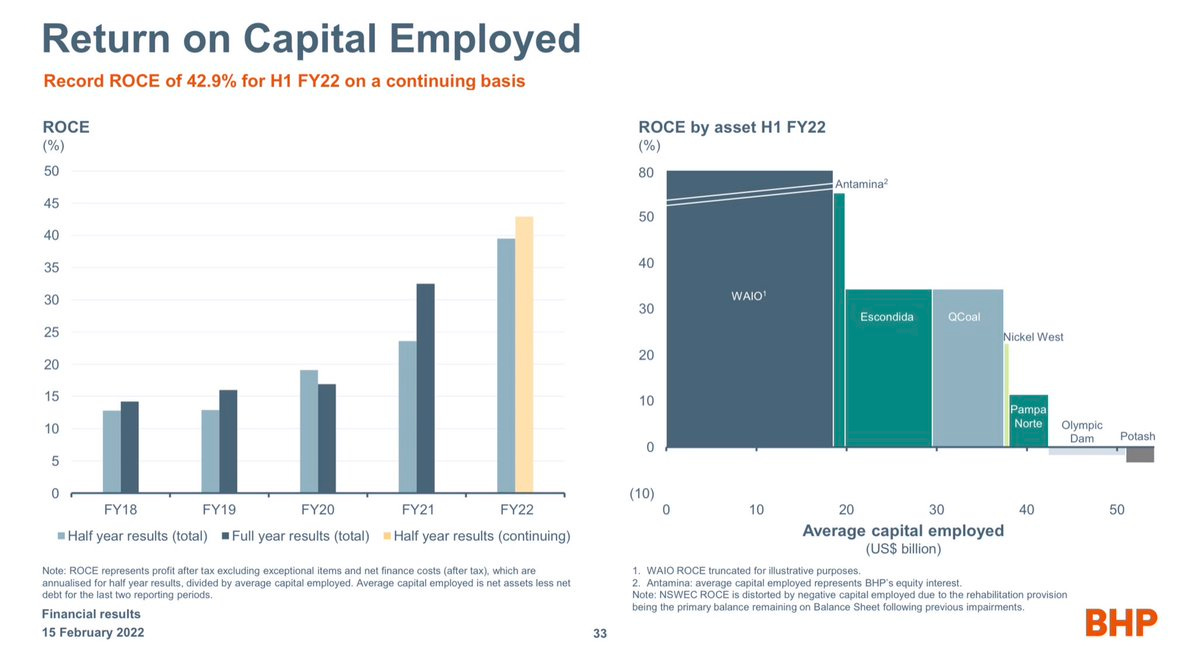

Oil is not an exemption. Let’s take this slide from mining giant BHP’s recent results with the returns on its current investments

Even with these 40%+ IRRs, BHP’s capex remains at a decade low, as investors stress cash returns and lower emissions over future growth

Ok, so far so good. We’re on the right track: less new resources, less production, less pollution. Right?

Unfortunately, no

To start, while the exclusion of high-emission industries seemed the right thing to do, it was also convenient. In the weak-demand decade following the Great Financial Crisis, the “dirty” sectors underperformed massively

Further, one might notice that all these measures address the supply side. But what about demand?

Demand changes are much more uncomfortable. Imagine not buying blueberries or avocados in your supermarket, not flying to the sun or not shopping online because it causes too many carbon emissions

However, over the past decade, demand remained sluggish. So supply shrank anyways, and no tough decisions had to be made

The low-demand morass was politically untenable. Social discontent increased and politics changed, culminating in the COVID-19 stimulus that shocked us into a new economic regime of high demand and high inflation

And now, with goods and services demand through the roof, commodity demand is through the roof, too

If demand is high and supply is low, what happens? Prices go up

We have already established that supply has been curtailed, so how is demand met? We run down inventories

Inventories are at record lows for many commodities, let’s take oil again as an example:

It’s not only oil, most commodity markets are historically tight

A record number of commodities are in backwardation, a market structure that indicates that current supply is scarce1

Because ESG-policies have changed companies’ incentive functions, we experience undesired side effects

Carbon emissions within Europe’s ETS scheme are UP (!) 6% in 2021 and bound to increase again this year, to return to the pre-COVID 2020 level only by 2025. They should shrink ~4% every year to keep with the EU 2030 target of -55% less carbon vs 1990

This is because natural gas has become so scarce and expensive that it is cheaper for utility companies to switch from gas to their highly polluting coal power plants

The nuclear power phase-out in Germany also contributes to this dynamic, as do outages at EDF’s nuclear plants in France2. Meanwhile, Poland continues to run on 70% lignite coal, the worst pollutant in the energy mix

And as long as the main renewable sources are weather-dependent, there is no alternative to carbon-run “baseload” such as coal or gas

The switch from natural gas to coal is a global phenomenon

Coal demand is now above it’s pre-COVID-19 peak, instead of a decline as forecast. Given it’s bad emissions profile, this is an upsetting fact

There are many similar interrelations between the various commodities

Some examples: Natural gas and food prices are connected, as gas is the key input for fertilizer. Food prices are also affected by rising aluminium prices which are needed for packaging, cf. Heineken’s recent results

With commodity prices much higher, energy and mining are the best performing sectors over the past twelve months. As many investors miss out on these gains, their ESG resolve comes under pressure

The CEO of Aviva, a big UK mutual fund investor and early ESG adopter, elegantly included “dirty” sectors again by stating to “buy brown and helping it become green”

Recent articles in the FT, the Economist or WSJ also reflect a broader change in attitude

But even if one were to forget about the environment (not good!) and throw ESG overboard, supply problems remain:

Again, let’s take oil as an example. OPEC+ was the historic swing producer, with spare capacity to provide to a tight market. This is no longer the case, underinvestment and maintenance problems have hamstrung its own production targets

With supermajors like BP or Shell restrained as outlined above, it is left to US-shale producers to expand production. In fact, they have been asked to do so by the Biden administration3. However, supply bottlenecks, crew shortages and escalating input costs make this impossible, as shale players Devon, Continental, Marathon or Pioneer recently stated

Ok, demand is off the charts and supply is severely constrained. But is that the entire story? Let’s have a look how this dynamic could change:

First, what about electric vehicles and renewables, surely they must make a difference?

Absolutely, much progress has been made in lowering Western CO2 demand, as can be seen in the chart below. This is unequivocally positive. However, Western emissions have also been “outsourced” - most of its goods are produced abroad, where emissions standards are different or entirely absent4

More so, the global growth in carbon emissions is driven by China’s and India’s rising middle class. They want the Western lifestyle, cars, TVs, spacious housing etc. Who can fault them?

Second, what about the economy? Many market participants expect a slowdown based on historic playbooks (e.g. Manufacturing-PMI cycles). That would reduce demand

Let’s use common sense: The world still hasn’t reopened yet, there are >10m open jobs in the US, you have to wait 10 months for your sofa, auto sales are still running 25% lower than 2019, the US consumer sits on a $2cash pile, US loans are growing, Europe’s fiscal stimulus takes effect this year, China is back to stimulating its economy etc.

This continues to be a red-hot economy, recent data confirms this, e.g. January US retail sales, industrial production, BofA February Credit Card data etc.

Third, what about escalating commodity prices itself, can they kill the economic recovery? I don’t think so, for the following reasons:

The driver of world economy is the US consumer. The US consumer - on aggregate - is in excellent shape and can digest much higher commodity prices. Estimates for the oil price level where US demand is impaired range from 150-220$bbl. The latter is equivalent to the 2008 oil price peak, adjusted for inflation (we‘re at 90$bbl now)

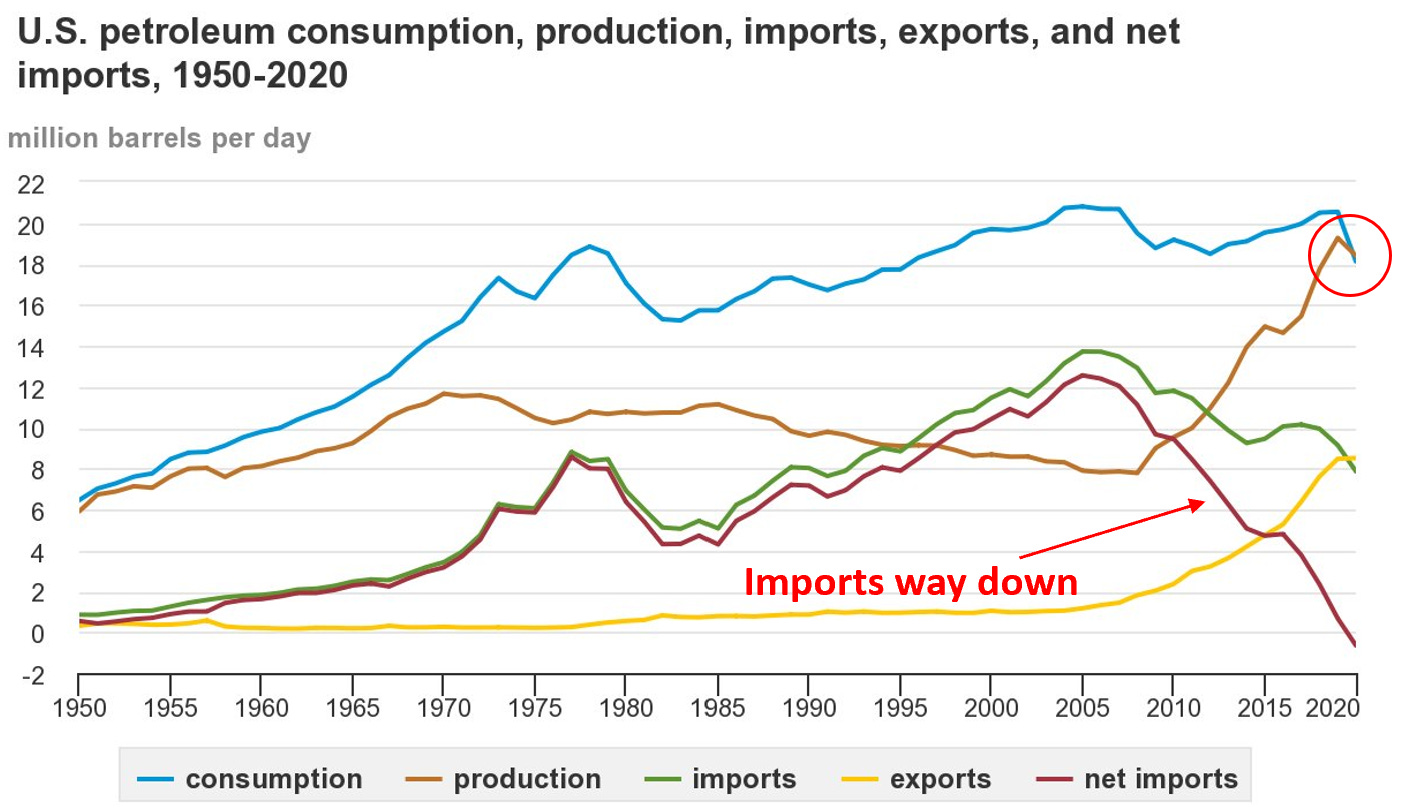

Irrespectively, with the expansion of shale oil over the past decade, the US has become self-sufficient in oil, as shown in the chart below. Said differently, the dollars Americans spend on oil stay in the country5

High commodity prices probably hurt European industrial companies the most. Europe is an big energy importer, its energy costs are significantly higher, and domestic demand is not as strong as in the US, so industrials margins compress

Ok, the environment is out in the cold, but at least the economy is on fire and the social problem is solved?

Unfortunately that’s not the case

While the economy - on aggregate - can digest higher commodity prices, these hurt lower-income groups overproportionally

First, they don’t own assets to cushion inflation

Second, food, power, gasoline are all bigger items in lower-income CPIs

Third, lower-income groups cannot easily divert to low-carbon alternatives. Living in the city-center is expensive, buying farm-to-table food is expensive etc.

So yes, with further rising commodity prices, we’ll eventually see a decline in carbon-intensive demand, as people who can’t afford it anymore are priced out. Is this a good solution? No, it isn’t. It’s a social disaster

Governments recognise this, so what do they do? They introduce subsidies to cushion the cost increases. Almost every European country has introduced multi-billion payments to its citizens to combat rising energy prices, e.g. £9bn in the UK, €8bn in Italy, or €9bn in France. The current US debate about the gas tax holiday strikes the same vein

While the subsidies are entirely understandable, they mute any demand response, leading ESG efforts ad absurdum

So what’s the outcome of all this so far? More demand, more carbon emissions, more government debt

Ok, we need to do something. But what’s the solution?

To start, we have to accept that there is no free lunch. We either reduce demand or pay up, a lot

Assuming it’s not possible to reduce demand, the cost of carbon has to be allocated in an equitable way, not overproportionally on lower-income groups

The best way to achieve this would be a global carbon trading scheme. Today, already 25% of the world’s carbon is covered by emissions certificates, with >40% in the EU. This is going in the right direction

However, there are still many exceptions, mostly to avoid hard decisions, such as carbon allowances for EU industrial companies. As a consequence, 90% of EU carbon savings are from power companies, contributing to the dynamics introducing in this post. The exceptions need to stop

To avoid social imbalances, energy costs should be subsidised for lower income groups. Yes, this isn’t perfect in terms of economics, but it’s fair. More so, if the subsidies are financed with proceeds from carbon certificates instead of new debt, they’re not inflationary

Certificates also lower the break-even for innovative solutions such as carbon air capture, and they incentivise producers to use less-polling resources. With proper carbon pricing the switch from gas to coal would not happen!

Looking at Europe, a higher EU-ETS carbon certificate price would pull forward the break-even for hydrogen gas, which could replace natural gas in its energy mix as clean alternative. Right now, it is still too expensive for broad application, forecast to reach standalone competitiveness only in the 2030s

Finally, how to tie this all together with previous conclusions about inflation, markets and the Fed?

The playbook remains the same as outlined in previous posts. Don’t fight the Fed, cash is king, sell rallies, hide in uncorrelated strategies. The US economy is running too hot, and commodity price inflation only increases the pressure on the Fed to act

Commodities face a historically strong backdrop. Their path of least resistance is up, until whatever the Fed does slows the economy

Where is the Fed action tipping point that not only brings asset prices down, but also decelerates economic activity? It’s unclear, but when it is reached, commodities will also suffer, so anyone wanting to buy them now should keep that in mind

Over the medium term, the changed economic structure of higher aggregate demand and continued underinvestment represents a huge tailwind for commodities. A good strategy for investors interested in exposure in this area is to wait for drawdowns to engage

One such drawdown is now offered by Russian oil & gas equities. They’ve sold off aggressively, pricing in extreme sanctions and further conflict escalation. In my view, that’s unlikely. If Europe introduces sanctions that curtail the existing flow of Russian commodities6, it would create more EU-inflation, which is already too high. It also seems likely that now is the moment of peak fear and Putin won’t go further than Donbass

Finally, while Renewables are being sold-off with anything Tech, their role has to grow if we want to make progress towards halting climate change. In public markets, US solar stocks look like the most promising sector long-term (but not yet)

Backwardation refers to spot prices trading higher than future prices (e.g. one or two years out). Contango is the opposite, when current prices are lower than future prices, as current supply is plentiful. This was at an extreme in May 2020, when oil spot prices hit negative territory

The nuclear debate is for another post, however, while the obvious conclusion may be that nuclear doesn’t emit CO2, one should keep in mind there is still no long-term solution for expired fuel rods, and the costs to clean up old sites are exorbitant

The recent advance in the Vienna Iran talks, as well as considerations to allow Venezuelan crude back into the US likely share the same motivation of increasing the supply of oil

Just think of all the goods made-in-china and currently powered with coal

The US GDP-intensity of oil also declined, by roughly 70% since the 1970s

Please note that Nordstream 2 is incremental

Hello Florian, very thoughtful article! We are deeply grateful you cited our work. Would you mind backlinking to our original post? https://kailashconcepts.com/crude-investing-energy-stocks-esg/ Thanks, KCR