The European Energy Crisis

A tale about the power of incentives

In my last posts I outlined how excessive monetary stimulus has created inflation, which will in turn lead to an increase in interest rates - a view I have received much pushback on. Since then, the prices of several tight commodities have spiked and interest rates are pushing up, as seen in the recent move of the US 10-year government bond1. In particular, gas and coal prices have surged dramatically, causing disruption to European energy markets, with the effects felt most starkly in the UK. The situation serves to illustrate the economic power of incentives, which is described below

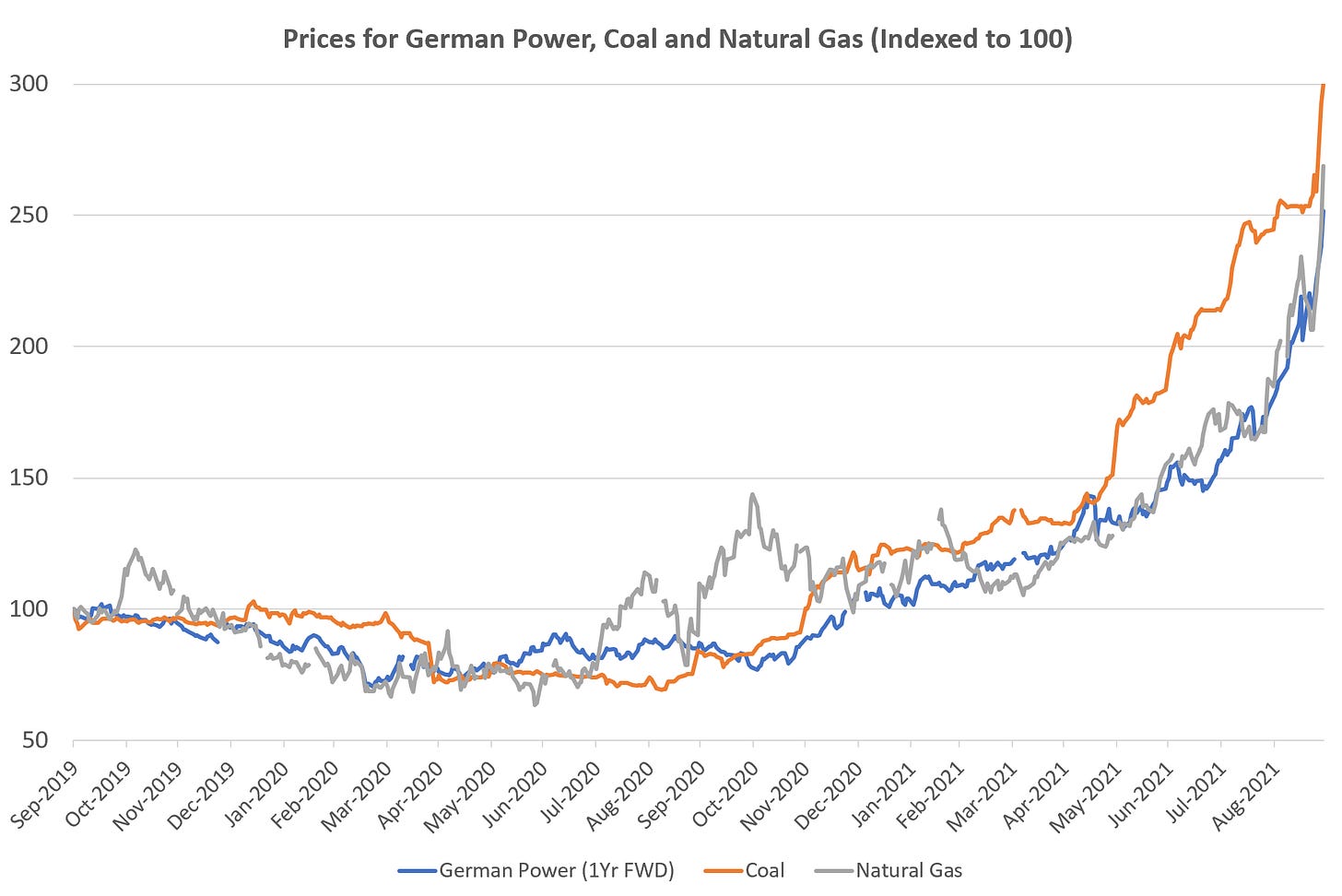

Over the past few weeks, European power prices have been going through the roof:

While the effect is painful on the continent, with several industrial companies halting production due to cost, it has caused chaos in the UK, visible in dramatic newspaper headlines over the past few days:

What happened?

To start, the global halt of economic activity following COVID-19 stalled expansion projects in the energy sector, thereby reducing future supply

No one knew the length or severity of the crisis, so the knee-jerk reaction was to cut spending and conserve cash

This dynamic was exacerbated by pressure from investors and governments on energy companies to cut CO2 emissions. As aging oil & gas fields were retired, few new ones followed

One year forward, demand has returned much faster than anticipated. Lockdown savings and trillions of government stimulus provided the means for an unprecedent spending spree, in particular in the US

While energy supply was reduced due to mentioned restraints, demand hadn’t gone through the same adjustment process at all

In fact, with government support focussed on cash payments (“stimmies”) instead of long-term investments into infrastructure or education, demand for goods was higher than ever before

And the production of all these goods requires lots of energy

For European power supplies, several dynamics aggravated the situation:

Renewables: European power is now highly dependent on wind and solar, and the past months have seen unusually low winds

Nuclear: Decommissioned nuclear plants left a gap in “baseload” (= power that is always on, irrespective of weather or night/day). This gap is currently bridged by gas and coal power plants, requiring imports of these commodities

Competing Foreign Demand: Russia decreased its gas supplies to Europe as it struggles to fill up its own stocks. China has increased gas purchases as it tries to move away from more polluting coal

Climate Change: Severe droughts in China and Latin America have reduced local hydropower generation, again increasing demand for gas and coal in a global market

For the UK in particular: the local power network is poorly connected to Europe. A fire in its main link to the French power grid essentially cut it off from the continent, taking away the ability to import power. A trucker shortage is more acute because of Brexit, and truckers are needed to distribute fuel to gas stations

The built-out of Renewables reduced the resilience of Europe’s power networks. Resilience is only ever relevant in periods of stress, which is now the case due to the global COVID-19 induced supply/demand imbalances

The growth and structure of Europe’s Renewable power is deeply connected to how humans behave as economic actors, lead by incentives. Let’s look into this in more detail

First, most humans care about others and their environment

This is a beautiful thought and motivation. It also makes sense because, as we all know, no man is an island. We are all a product of our environment and connected to each other, and this extends from family, neighbors and friends to nature and our surroundings. So when the environment visibly deteriorates, we want to do something about it

And for the avoidance of any doubt, we do have a real problem. No chart tells it better as the one below. Global warming is accelerating in a scary way:

Second, we have an equally inborn mechanism to avoid effort. Effort requires energy, energy used to be very scarce, so we’d rather avoid it. To reconcile both motivations, we subconsciously prefer solutions that are (1) more borne by others or (2) have to be paid further down the line. The environmental debate is full of these asymmetries

Environmental policies typically originate from Western urban elites who have the highest energy footprint in the world. Yet policies are often overproportionally carried by low-income or rural demographics (e.g. commuters relying on cars)

Similarly, we often single out Emerging Markets as environmental offenders, yet we are not willing to lower our own living standards to reduce our CO2 footprint

In the investment world, “ESG”-policies are in-vogue, where companies with a high carbon footprint are excluded from investment decisions. This was highly convenient as long as high-ranked “ESG”-companies such as software would do well in the age of falling interest rates

Finally, the main political avenue to lower CO2 emissions was to provide subsidies to environmentally-friendly power suppliers. In other words, the government would pay the private sector to build wind farms or solar parks, and finance it by issuing government debt

This had the twin effect of pushing the cost into the future (debt) as well as avoiding adjustments to the demand side (i.e. no one was incentivised to change their consumption behavior, buy less goods, take fewer trips etc.)

Third, we overestimate our own planning capabilities. History is littered with failed attempts of central planning, from the obvious Politburo experiments to Central Banks trying to steer the economy with negative interest rates. A top-down environmental strategy runs into the same difficulties

To put it simply, if the market is incentivised to build wind farms, it will do so until the payments stop, whether it is still sensible or not. Results of these policies are often overbuild and graft

However, if the market is incentivised to lower carbon emissions, but left to itself in figuring out how to do so, it would be forced to come up with ingenious solutions. This incentive would be achieved with a carbon tax instead of subsidies (see below)

Leaving it to the market to find a solution does not at all mean it would have to be socially unfair, to the contrary. It is simply about using incentives to redistribute more efficiently

So where are we now?

Europe has spent hundreds of billions on renewable energy subsidies, and European government debt is at astronomical levels

European CO2 output has declined somewhat, which is a tiny (but necessary) drop in the ocean of global CO2 emissions. Could we have done a lot more with different incentive mechanisms?

Right now, the bill is paid overproportionally by the little guy. Energy costs are going thru the roof, and low-income households spend >10% of their income on energy:

What could be a good solution?

Looking at the power of incentives, a carbon tax stands out in aligning economic and environmental interests

CO2 emissions produce a cost (environmental damage), that currently is not paid by the emissioner, but by all of society. Putting a price tag on these emissions brings together cause and cost and incentivises CO2 reduction both on demand and supply side, instead of supply side only in the case of subsidies

These should be regionally different given varying purchasing powers between economic blocks. Imported goods from lower carbon tax areas (e.g. emerging markets) can be assigned a mark-up, similar to VAT-regimes

The proceeds to the government from such a carbon tax can be invested in (A) early stage research, where private sector deficits in innovation are the biggest and (B) a balancing mechanism to reduce the burden on lower income groups

There are some attempts in this direction

The European emissions scheme goes in the right direction, but it is too timid to have caused any behavioral changes over the past 15 years since its inception

Germany has introduced a CO2 tax on gasoline and diesel. But again, who’s overproportionally paying for it?

Conclusion:

There is way too much money chasing too few goods, and we are witnessing inflation as a result. While prices are going up everywhere, the collateral damage is significant in the energy sector where a confluence of factors has reduced resilience to shocks

These dynamics will continue in the short run, and continue to put upward pressure on interest rates - the only valve to absorb all this excess cash

Higher interest rates are negative for most asset valuations, in particular anything with high leverage or high valuation multiples. I’ve introduced some areas to “hide” from these dynamics in recent posts - beyond that, the by far best protection for this scenario of rising rates and compressing asset valuations is to simply be in cash

Generally regarded as benchmark for all yield-sensitive assets