The Ferrari Economy

Bailouts are back, but will the public bear them after a decade of inequality?

Two weeks ago I wrote a post that was my most-read yet. Titled “The Wile E. Coyote Moment is Coming”, it described how an increasing share of US consumers is running out of savings, with the troubling realisation that the “lower 80%” are now in a worse financial position than pre-Covid, while the top 20% are still comfortably ahead

This broadening consumer pain coincides with the return of bank bailouts, something last seen in the Great Financial Crisis ‘08/’09. The GFC also ushered in a period of accelerated inequality, to which said bailouts contributed in no small way. Corporate losses traditionally born by share- or bondholders were socialised to taxpayers, who paid for it with years of austerity and sluggish real wage growth. Meanwhile, the corporate sector and its shareholders soon thrived again as QE and other easy-money policies revalued their holdings and profits

Now bank bailouts are back, and the US government faces some tough choices ahead. Will it prioritise corporate stakeholders again and risk the rage of a populace that increasingly had enough of oligarchic policies at their expense? Or will it honor moral hazard and let bad actors fail, and with it risk unintended consequences that quickly feed into the real economy and thus, employment?

This posts walks through what I see as likely path ahead, and as always closes with a current outlook on markets

Since last Spring, the net financial position of most Americans has worsened significantly

While most income brackets still hold more savings than pre-Covid, high inflation forced them to increase their debt to maintain spending. Thus, higher credit card, consumer, auto or mortgages loans now more than offset higher cash balances

However, the top 20% were much less affected by these dynamics. Why?

They save a large share of their income, as you can only spend so much to cover all needs. Inflation therefore hits them much less hard

The result is a bifurcated economy, where 80% increasingly struggle while the top coast away

Financial markets are unemotional, and they reflect this “hunger games” development in the share price performance of companies that cater to the different demographics. Some examples:

Ferrari, which sells its supercars at an average price of $634k, is trading near all-time highs. It has outperformed Dollar General, a popular US mass-discounter by 60% over the past half year

Luxury-fashion market leader Louis Vuitton is going from strength to strength, with 23% revenue growth for ‘22. Mass supermarket Walmart underperformed it by 20%

Comments from Jeffery Owen, Dollar General’s CEO, corroborate these charts:

So Ferrari can’t sell enough cars, while Dollar General’s customers have to borrow from their friends (!) to make means end - how did we get to this place?

It seems that whatever is done, it hurts the lower 80% the most:

First, ten years of QE inflated asset prices out of reach. Middle class dreams like home ownership became unaffordable (see “Incentives and Inequality” for details)

Then inflation followed, which again hurts those who spend the bulk of their earnings

Now bailouts are back into this socially, highly problematic context

The American public is acutely aware that the past bailouts immensely benefited asset owners, both via higher asset prices through QE, but also via many other facets such as higher corporate concentration, weaker worker bargaining power etc.

Looking at the share of corporate profits in GDP, the outcome is stunning. Over the past two decades corporates profits grew to a record share of GDP that further went into overdrive after Covid-19 (NB: other dynamics such as globalisation also played a role)

Summary: Bailouts re-emerge at a time where most US consumers are severely struggling and the American public’s tolerance for corporate favoritism is materially strained

But why will we need more bailouts in the first place? Is it not done and dusted with Silicon Valley Bank, Signature and Credit Suisse all sorted out?

Unfortunately, we likely just saw the first of several bailout waves. Why? A hard landing is firmly on the way for the US economy, and that will cause more pain for the financial sector

While the Silicon Valley Bank crisis made headlines on front pages, economic data in the back pages continues to deteriorate, as I predicted in “Hard Landing, Soft Landing or Moon Landing”

Import volumes at L.A. port, which handles 40% of US import volume, are now back to 2016 levels for this time of year and 43% lower than last year (!)

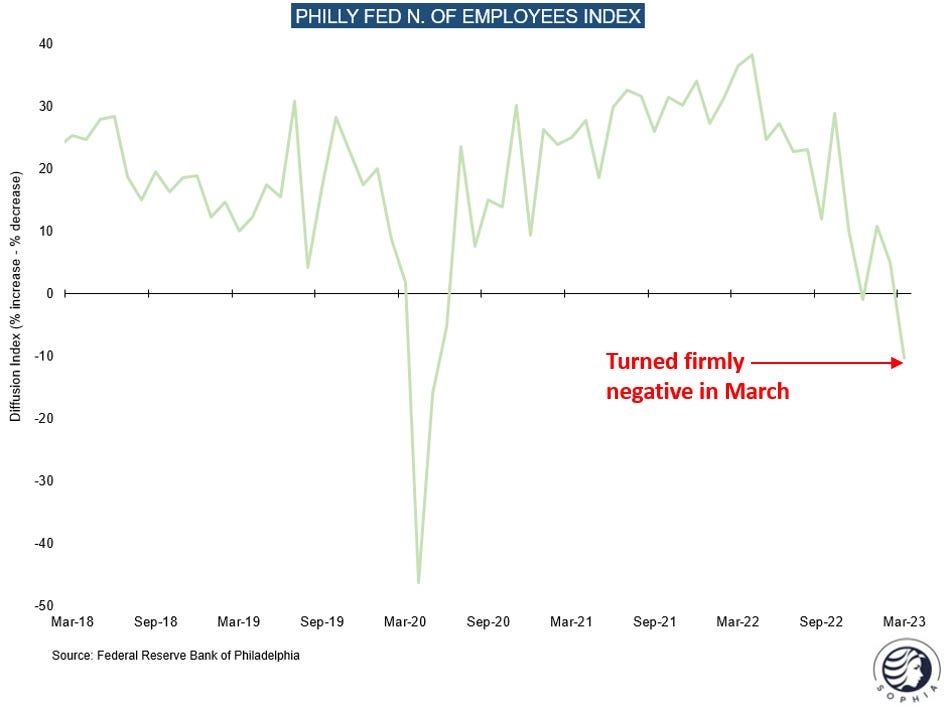

Lead indicators for unemployment have worsened, as the employment part of the Philly Fed Manufacturing Survey illustrates

Please keep in mind - layoffs in manufacturing are historically enough to significantly increase the unemployment rate

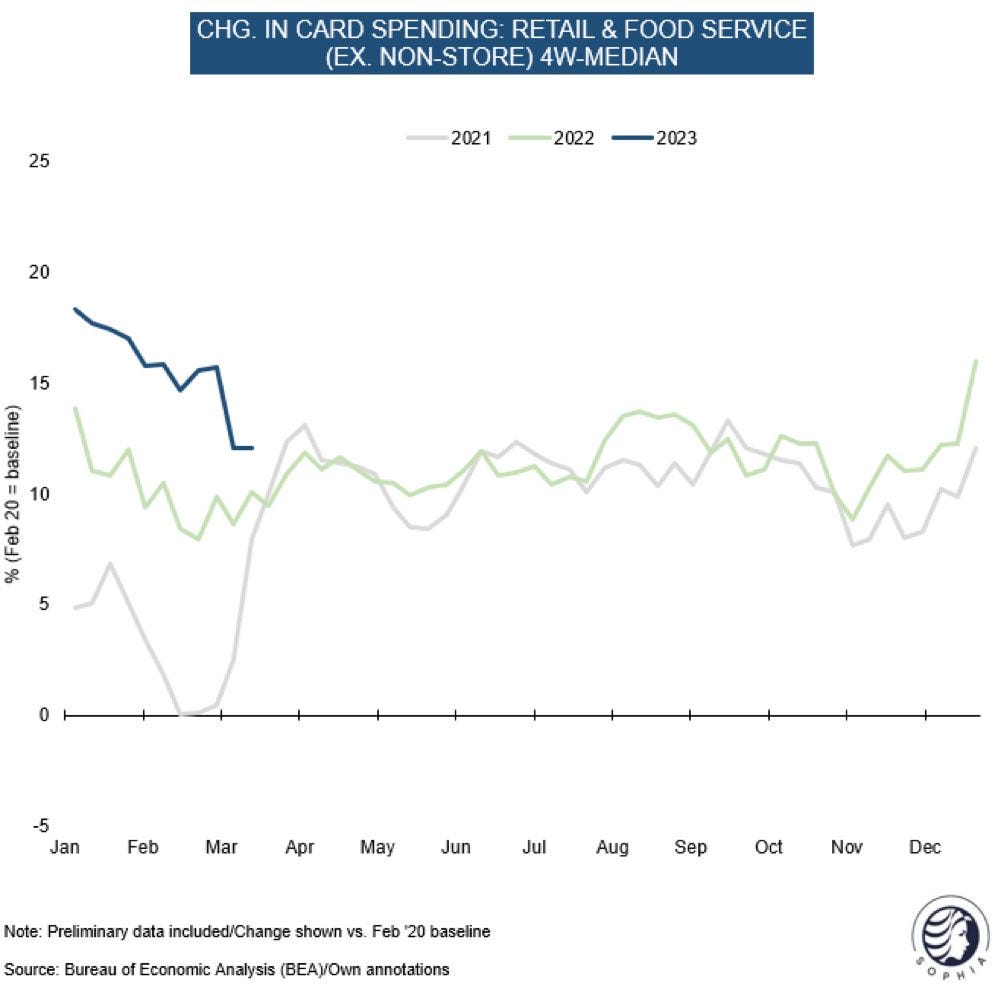

Further, consumer spend weakened visibly in March

While one might suspect banking headlines behind it, the events are likely too recent for it. The true reasons likely are lower than expected tax returns and a reduction in SNAP benefits, several of many consumer headwinds this year

Comments from retailers such as Citi Trends (discount clothing) or other banking card data confirm these conclusions

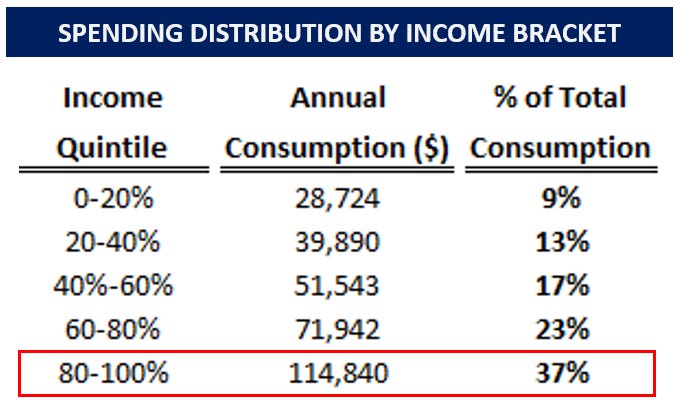

But what about the top 20% - they are still on fire, and can carry the economy?

That seems unlikely. While they are punching above their weight, the top 20% account for ~40% of consumption, not enough to change the economic trajectory

Now, what does a seriously slowing economy do to banks? Simple - it increases losses in their credit books

Once again, Real Estate stands out, in particular commercial RE, a ~$5tr mortgage market, of which 30% pertains to offices, or c. $1.5tr (all stats from GS)

US office occupancy has dropped to ~50%, so companies are cancelling leases as they roll off, with no one interested to take them over. This market segment is the “subprime” equivalent of this cycle, where huge write-offs are likely to occur. NB Subprime mortgage size in 2007 was ~$1.3tr

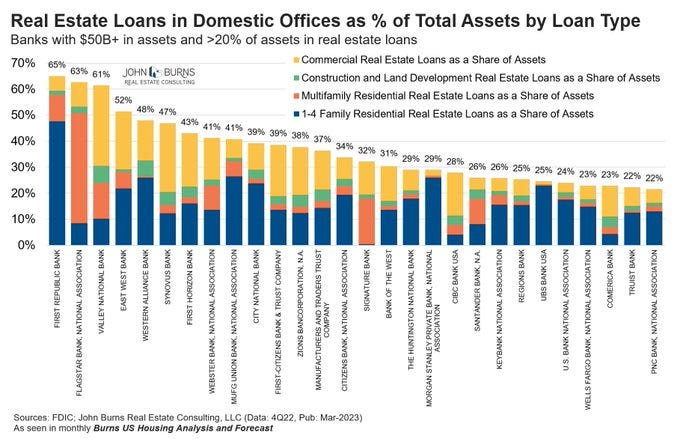

Who owns a lot of these likely toxic mortgages? You guessed it - US regional banks, the same banks that just made headlines over the past weeks (see “From Inflationary Boom to Deflationary Bust” for details)

Fighting for market share against big banks advantaged by size and QE (e.g. reserves), they went up the risk curve with their own balance sheet

It is not only offices, regionals are also stuffed with other real estate exposure, from Californian millionaire mansions that are down ~20% (First Republic) to multifamily overbuilt (Flagstar, Citizens)

Again, history repeats itself

Fed easy money opened the chase for higher returns

US regional banks were allowed to be careless as they got deregulated

Now they own toxic assets and will likely need to be bailed out

Summary: The first wave of bailouts was about interest rates mismatches. As the economy deteriorates, the second wave likely emerges, driven by significant loan losses, in particular in commercial real estate

Meanwhile, a steep rise in both FHLB funding and borrowing as well as significant inflows into the Reverse Repo Facility indicate that the deposit issues for regional banks are far from over

When an overlevered economy goes into a deep recession following an asset bubble, it is in urgent need of liquidity. Why?

High leverage means that large amounts of credit continuously need to be refinanced (e.g. $300tr global debt, av. 5 year maturity = $60tr this year)

However, as the economy declines, customary lenders nurture loan losses (see above). They are therefore unable or unwilling to roll over existing debt to the same degree as before. Further, the economic decline lowers earnings for corporate and income for households. Thus their creditworthiness is impaired

A refinancing gap opens across the economy. It has to be shut somehow, exactly at the moment when no one wants to extend credit. In the absence of new credit, earnings and income deteriorate further. Hyman Minsky’s work on credit cycles is instructive for this stage, with the “Minsky Moment” made famous as culminative turning point. We likely are at a similar moment now

Interest rate cuts only partially address these dynamics. If a bank needs to curtail lending due to loan losses, it won’t help much if rates are lower. If a company is overlevered, lower rates won’t make it more eligible for credit

What the economy really needs at that stage is not only lower rates, it needs new money. And this new money can only come from the government, i.e. the printing press, which then finances all forms of bailouts

Without new liquidity, mass defaults follow, and with it high unemployment for an extended period of time

But providing printed money to the economy comes at a steep cost. Unsound structures are maintained (“zombie companies”) and extract unwarranted rent from the economy. Excessive risk taking is rewarded. Most importantly, inflation may rise

When bailouts enter the scene, governments face a very tough job in walking the very fine line between preventing an economic collapse and avoiding moral hazard and inflation. And after the past decade and the experiences of the Great Financial Crisis, the public’s eye is sharpened towards the latter

As a consequence, affected governments so far were at pains to even use the world bailout. This sensitivity likely increases after the rescue efforts for Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Credit Suisse were thrown under the spotlight. The echo for SVB looks particularly ugly:

SVB’s failure was made possible in the first instance by a deregulation push that SVB’s CEO pressed hard in Congress. The same CEO sold $3.6m shares days before the blowup

SVB gave founders preferential personal loans in exchange for their companies’ business. This favored SVB over other banks at the expense of founders’ investors

It turned out that politicians who lobbied for SVB’s rescue had close ties to the bank, such as California governor Gavin Newson or San Francsico Congressman Ro Khanna. This is a bipartisan phenomenon, the other now defunct regional bank Signature threw fundraiser for Republican chair of the House Financial Services Committee just a week before its demise

SVB’s $70bn loan book is likely low quality, with loan losses highly likely down the line. As deposits are now entirely guaranteed by the FDIC, these loan losses will later be born by ordinary Americans instead of the VC ecosystem. Even if other banks cover them, these will in turn increase their banking fees to make back on these costs

The public’s feedback for SVB likely increases hesitancy on further bailouts down the road - just what happened in ‘08 when the Bear Sterns bailout influenced the decision to let Lehman go down six months later. Two examples already illustrate this dynamic:

First, in Switzerland, legislators were at pains to inflict damage to asset owners by wiping out the $17bn AT1 bonds in Credit Suisse’s takeover by UBS. However, once these write downs are considered, UBS still bought CS for “minus $15bn”, with a $9bn state guarantee on top. At the same time, consumer choice for Swiss domestic bank will shrink going forward. Again, ordinary citizens pay the bill in the long run, via fees and taxes

Second, on the US regional banking crisis, the government is clearly hesitant to get involved more broadly. Janet Yellen first implied a broad deposit guarantee a few days ago, just to walk back on it at a Senate hearing yesterday. At the same hearing, she explicitly stated that “taxpayers won’t be bear the cost linked to failed banks”

Janet Yellen is stuck between a rock and a hard place. Blanket deposit guarantees are bad for moral hazard. If banks can take deposits for granted, they again go up the risk curve to do stupid things1. If she does nothing, the deposit issue for regionals will continue to simmer and worsen the credit crunch already under way

Conclusion:

The US economy is steering into a hard landing that will lead to high loan losses at regional banks and other financial institutions. A second wave of bailouts is likely, while the current one has barely stabilised

Public support for bailouts is limited and backlash is high after a decade of rising inequality, topped off with a now bifurcated economy between top 20% and bottom 80%

Politics follows public opinion, as such bailouts will be done with hesitancy, and with the intention to impose heavy costs on asset owners, rather than the tax payer

This is a positive development for the long-term health of the economy. But it likely comes at the steep price of a deeper crisis

Irrespectively, material liquidity provision by the government is the likely inevitable end-result. Contrary to what many in the market expect, it will likely be a lengthy road to that, especially while inflation readings remain high

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

Bonds - I remain of the view that US Treasuries are the key trade of the year. Please see here and here for more details. I remain max long this asset class across the curve. Inflation likely stays high for the coming months (I expect a March CPI headline print of ~5.2% y-y) but after should tail off meaningfully if most CPI lead indicators are correct (cf. Philly Fed Services Survey, Wages & Prices Paid). As the economy is likely increasingly liquidity-starved, US Dollars and US Treasuries are likely some of the few assets left with a bid

Equities - The current stage of the economic cycle is congruent with “risk-off”, which describes the wholesale disposal of all assets in exchange for liquidity, which is needed to repay credit. As such, I expect equities to sell off significantly. I’ve been waiting to engage on the short side, but think the time may now have come, so I’ve positioned accordingly with puts on cyclical sectors. Exuberance returned to parts of the market (e.g. meme stocks), the put-call ratio hit a recent low suggesting market participates underestimate downside, and positioning is off the lows. Further, credit stress likely increases from here, with commercial real estate as focal point, which for obvious reasons has never been good for equities

Levered Loans - Aside from commercial real estate, this is likely the other toxic credit category. I see much asymmetric downside here as corporate earnings decline and credit dries up

Commodities - It is very simple. As I’ve frequently written, the current stage of the cycle is not good for commodities. I expect these to do well again only when the cycle turns, potentially in Q4 ‘23, possibly later

Gold/Crypto - These asset classes will likely get hit in risk-off, to likely do well once QE or similar measures return, which is - in my view - significantly later than many in the market currently assume. As such I still remain very cautious here

Should I be right with my analysis of the economic cycle (NB: as always, I may be wrong), then investors are likely well served with US-Dollar cash and Treasuries, until the market forces the Fed’s hand to return to the printing press. I expect much (!) to happen before that is again the case

DISCLAIMER:

The information contained in the material on this website article reflects only the views of its author (Florian Kronawitter) in a strictly personal capacity and do not reflect the views of White Square Capital LLP and/or Sophia Group LLP. This website article is only for information purposes, and it is not intended to be, nor should it be construed or used as, investment, tax or legal advice, any recommendation or opinion regarding the appropriateness or suitability of any investment or strategy, or an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, an interest in any security, including an interest in any private fund or account or any other private fund or account advised by White Square Capital LLP, Sophia Group LLP or any of its affiliates. Nothing on this website article should be taken as a recommendation or endorsement of a particular investment, adviser or other service or product or to any material submitted by third parties or linked to from this website. Nor should anything on this website article be taken as an invitation or inducement to engage in investment activities. In addition, we do not offer any advice regarding the nature, potential value or suitability of any particular investment, security or investment strategy and the information provided is not tailored to any individual requirements.

The content of this website article does not constitute investment advice and you should not rely on any material on this website article to make (or refrain from making) any decision or take (or refrain from taking) any action.

The investments and services mentioned on this article website may not be suitable for you. If advice is required you should contact your own Independent Financial Adviser.

The information in this article website is intended to inform and educate readers and the wider community. No representation is made that any of the views and opinions expressed by the author will be achieved, in whole or in part. This information is as of the date indicated, is not complete and is subject to change. Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although believed to be reliable, has not been independently verified. The author is not responsible for errors or omissions from these sources. No representation is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of information and the author assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise such information. At the time of writing, the author, or a family member of the author, may hold a significant long or short financial interest in any of securities, issuers and/or sectors discussed. This should not be taken as a recommendation by the author to invest (or refrain from investing) in any securities, issuers and/or sectors, and the author may trade in and out of this position without notice.

See this Chicago Fed paper from 1986 for details

Florian, it is always a pleasure to read it. I have not done much statistical work, but I am surprised by the resilience of the economy. The results of many companies are ok. Restaurants are full, etc. How is it possible that things are not visibly better than one could expect?

Excellent piece, Florian. I literally read hundred+ market/economic reports weekly, and yours is by far one of the best. I really like your, “What does this mean for markets” section. Well done and thank you.