The Hedge Fund Dilemma

How equity markets have changed, how the hedge fund model hasn't, and what may be a future blueprint for the industry

Hedge funds have a history going back to the 1930s, but they really came onto the map of modern finance during the stock market boom of the 1990s and then following the burst of the new economy bubble, when equity long/short funds in particular provided protection from declining markets as well as high returns. Since then, trillions of dollars of capital have poured into the strategy, and traditional sources of alpha have been reduced. Accelerated technological disruption will put further pressure on the business model as cheaper alternatives attempt to replicate what it offers. What is the future for the industry?

The recent history of hedge funds is a story of two halves. From the late 1990s until the mid 2010s, and the period thereafter:

Between 1997 and 2016, hedge fund assets grew ~30x, from c. $100bn to $3tr, in part due to an appreciating stock market (the S&P rose ~2.7x over that period), but mostly due to rapidly increasing capital allocations

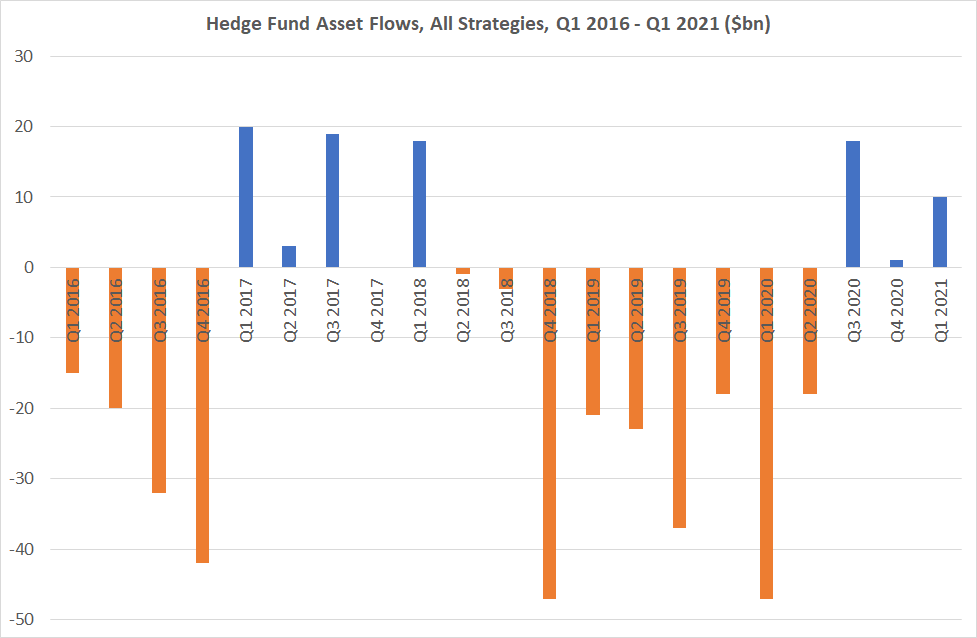

From 2016 to 2021, hedge fund assets rose by another ~$1tr. However, this time, all of the increase was borne from stock market gains. In fact, over the same period a total of $230bn had been redeemed from the industry despite a rapidly growing overall capital stock, as visible in the chart below

While all hedge fund subsegments have been facing the same trend, this was most pronounced in strategies summarised as equity long/short. It accounted for half the outflow in comparison to a quarter of industry assets

Equity long/short is the original hedge fund strategy and means nothing else but the practise of running a balanced portfolio betting on stocks appreciating (longs) and declining (shorts), thereby capturing steady performance independent of the market (= “alpha”). This is the largest subsegment within the hedge fund industry, and what this post is focussed on

Now, looking at the aggregate alpha across the industry, the reasons for the growth reversal quickly become apparent. The below chart shows that cumulative industry alpha peaked in 2009, just after the financial crisis, and has been in decline since:

What happened? It’s very simple. The massive influx of capital, together with the much improved access to information, made capital markets much more efficient

Looking at the equity long/short model in particular, the evolution can broadly be described as follows. Keep in mind this is for the average, liquid, large cap stock (Microsoft, Visa, GM, Volkswagen, etc.) where most of the trading volume takes place. There are many niches where different or diminished dynamics are at play, such as biotech1, small caps, event-driven, equity placings, activism etc. However, these are often cyclical or face capacity constraints

In the late 1990s, the bedrock of the equity long-short model was very simple and exemplified by Julian Robertson’s Tiger Management, a portrait of which has recently feature prominently in the FT. You go long the 20 best companies and short the 20 worst companies you can find. The market will not have fully understood the fundamentals of the respective businesses and come around to it over time, creating big moves in stock prices

This approach remained the same over the next decade. However, other market participants improved their understanding, and hedge fund assets grew, so the edge became more specific and moved to predicting quarterly earnings, often with elaborate models tracking profit & loss inputs, managed closely by frequent meetings with company management, industry expert calls, etc.

As this practice became more prevalent and lost its edge in the early 2010s, the practise of data-tracking was introduced, in-house or via external service providers. This would include website scraping, counting ships outside ports, counting cars in factory parking lots, checking glassdoor job openings or similar near-time efforts

In other words, the fundamental research process for large cap stocks today is pretty much exhausted. It requires several magnitudes more effort for an ever diminishing advantage. That’s is not a bad thing - efficient markets are a positive for society

But prices still move around a lot, so what’s causing those moves? In a simplified point of view, three dynamics are at play:

First, there is the economic outlook (“macro”), which obviously has a huge impact on companies’ fortune and can affect different sectors in different ways. The economic outlook is reflected both in future earnings estimates as well as in the level of interest rates on government bonds, which represent the benchmark of which all financial assets are priced off. These rates going up or down will affect different types of stocks in different ways2 and forecasting them is a different science altogether

Second, there is positioning, the game of guessing what everyone else thinks. Sometimes this can be quite obvious, but everyone is looking at the same data and one needs to come to a conclusion diverging from that of all the other smart people in the market

Finally, there is liquidity and flows, which is driven by the likes of savings rates, quantitative easing, share buybacks etc.

The following chart shows the alpha for equity long-short funds for each year since 2016. It is created by Morgan Stanley’s Prime Broking unit, which given its market-leading position holds assets for a representative amount of equity long/short funds3

The grey line is the average for 2010-20 (excluding the so far poor 2021, more on that below) and comes out at ~5% p.a. Keep in mind this is before performance and management fees are deducted. A 5% pre-fee return is clearly insufficient to attract investors, so what can managers do to improve it?

Many have in the past turned to the following options to increase returns:

Take more beta (= long the market). The easiest way to do this is by having more long than short exposure. And indeed, the average equity long/short fund today runs its book at about 65% net long, a historical high4. There are also many other ways to assume beta into a portfolio, e.g. thru biases in single stock selection

Take on leverage. Leverage is cheap (0% overnight…), and the typical single manager portfolio is often run at 140% long exposure or more

Bet on a factor such as growth, momentum or value. The most popular way of achieving this has been to pick growth/technology stocks on the long side and value stocks on the short side. For the most part of the decade this has worked exceptionally well, in part because falling interest rates revalued assets with long duration, but also because technological change has been accelerating

Unsurprisingly, today, the long “tech” - short “secular decline” approach is totally overrun and probably the biggest contributor to the poor aggregate alpha result in 2021 as per the MS chart above

As beta, leverage and factor exposure can easily be replicated with low-cost alternatives, some investors saw thru it and re-allocated their assets. So equity long/short funds made further efforts to tilt the balance in their favour, and two successful ways stand out:

Moving into private assets. It may be surprising that 3 out of the biggest 5 venture capital investors of 2021 are in fact hedge funds. Especially the Series-D/Pre-IPO market has shown considerable returns into public market listings (selling to overexcited retail investors?), but the activity levels have also extended to earlier rounds

Consolidation. This is probably by far the best answer within equity long/short , and an unsurprising one, as it’s a template observable in many industries under pressure

Instead of a single manager grinding away trying to push the 5% alpha to a level acceptable to put fees on top and thereby assuming more portfolio and business risks, why not combine a large number of such managers together who are all slightly uncorrelated, thereby creating a low-volatility return stream

The return stream can then be levered up many times to get back to the historical high-teens IRR. This is the simple concept behind the success of platforms such as Millennium or Point72, whose assets ballooned in recent years. In addition, several macro hedge funds with a broad mandate and many portfolio managers resemble this model

If the hedge fund space (and in particular equity long/short) on aggregate is losing assets, where are the assets going? Two areas are the main beneficiaries:

Low cost alternatives such as passive ETFs that usually simply track indexes, or increasingly active ETFs, which combine the low cost of passive ETFs with some elements of active management. ARK Invest is the most prominent example. The chart below shows impressive, uninterrupted growth in aggregate ETF assets over the past 30 years

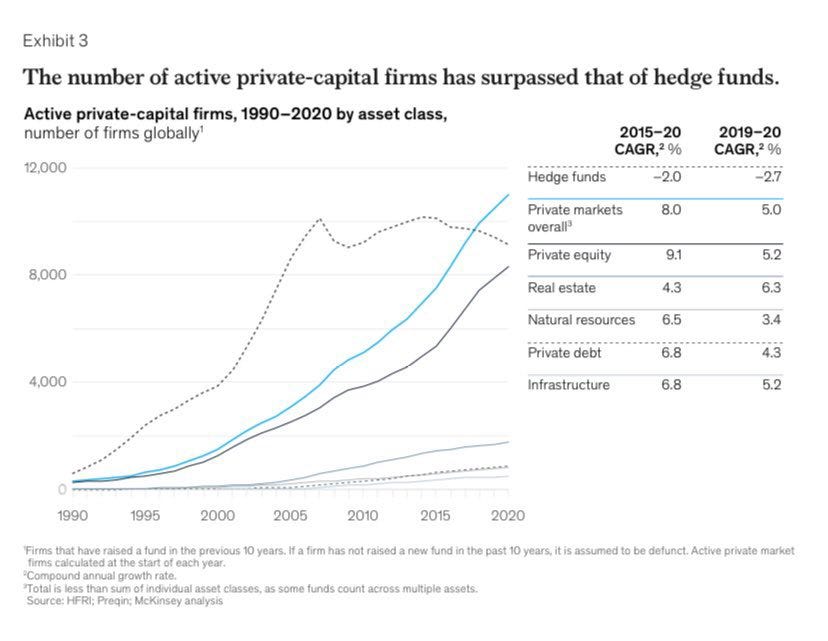

Funds active in private markets such as private equity, growth equity or venture capital. As is well visible in the chart below, the number of private equity funds and similar models has steadily risen over the past decade, while the number of hedge funds peaked around 2005

Now, are private equity investors considerably smarter than their hedge fund counterparts? It’s possible, but looking at the typical biographies of employees at any of these firms, you will find the same HBS, Wharton Business School etc. everywhere. So what’s different in private markets? There are three distinct drivers:

The barriers to entry are (considerably) higher. Anyone with $50 in their Charles Schwab account can buy stocks. It’s much more difficult to buy a company and the process needs to be skilfully managed. Relationships are very important, and particularly in venture capital the right brand can far outweigh the ability to pay up

While financial theory would assign a discount to illiquid assets, private markets as an asset class may in fact benefit from an illiquidity premium as Clifford Asness from AQR describes it here. The fact that immediate performance data is permanently available in public equities creates many unhealthy incentives on either side of the business model, from investors basing decisions on the latest quarterly performance data to fund managers trying to optimise near term performance to avoid exactly that

David Swensen, the recently deceased Yale endowment CEO who pioneered the allocation shift away from fixed income and into private equity and hedge funds, described PE as “levered small caps with control”. In 2020, the Russell 2000 (US small cap index) declined 41% during the Covid-19 crash to then finish the year up 25%. Imagine the same numbers with just 1x leverage on top

Finally, declining interest rates are an important driver behind the boom in private markets over the past decade. Any strategy that was long the market, with leverage, has benefited from the ensuing lower borrowing costs as well as multiple expansion. The chart below shows the increase in earnings per share for the S&P 500 in comparison to the increase in price, with the delta attributable to said multiple expansion. Assuming rates had stayed the same over that period, returns would accordingly have been roughly 50% lower (and the entire financial industry much smaller…)

Now, just because fundamental information is largely efficiently priced in, that doesn’t mean that there aren’t big trades around anymore. Positioning can drive huge dislocations that can be very profitably exploited. However, the rigid long-short model in particular is an enemy of the ability to exploit these. In fact, it contributes to them:

Too much money in the same strategies with the same parameters has the effect that everyone becomes a forced seller at the same time. Typical situations can be e.g. that many funds are long growth stocks, then rates rise, which triggers a selloff in said growth stocks, leading to short-term drawdowns that become a threat to the business (see above), so exposure has to be cut, leading everyone to liquidate at the same time

This then occurs exactly at the time when exposure should actually be added, taking advantage of these dislocations. One might call this process the equity long/short “washing machine”, where the structure of the business determines a noisy, procyclical iteration of adding and cutting exposure, like laundry thrown around as the washing machine goes on. This is much more pronounced in down- or sideways-markets, when there is no beta to bail out performance

So what does all this mean for the hedge fund model going forward, particularly in public equities?

When the average long/short fund can be replicated by two Morgan Stanley indexes at essentially no cost5, and the structure furthers behavioural trappings, the model will most probably have to evolve from its current form

Dislocations remain plentiful, and it’s worth patiently waiting for them. Therefore, a hybrid model may become attractive where managers focus on high conviction ideas and co-invest in those with their clients as they arise, and the remainder of the time the funds stay in passive or active ETFs

In the same vein, the established hedge fund strategies might be available as semi-active building blocks to easily enter and exit whenever the opportunity set is benign. For example, merger arbitrage would lend itself well to a semi-automated, active ETF where investors have the ability to come in and out in a flexible way, same for equity long/short

The cost and flexibility for all individual strategies will come down. The fund model will possibly be further dissolved. The skill will be to call the dislocations, allocate capital to them and move on once the trades have played out, something that in fact elevates the role of the capital allocator

A word on the role of information

Information on public equities has been truly democratised. There is an overflow of information for each and every listed company online that can be accessed with a few mouse clicks. This trend will only intensify. It is still noisy and chaotic, there is no curation or quality filter, but the information is there

Raw information by itself is just one part of the story, the other is skilled and experienced individuals working with such information. When people collaborate, the magic of 1+1 > 2 happens. There is a movement in its early infancy where the collaboration on ideas happens in the public domain, allowing experts to easily connect with each other when they might otherwise not have had any touchpoints

Anticipating these developments, there might be a significant first mover advantage for the investment firm that decides to put all its analysis online, for the public domain, for free, and then benefits from the gravitational pull of the exchange of thoughts that might ensue. In Venture Capital a similar train of thought can already be observed, for example in Andreesen Horowitz’s new online content platform “Future”

Just like in any other industry, change is the only constant. New business models will emerge. It will be exciting to see what they look like and they might be very different from today’s

Four out of the five top performing hedge funds over past decade are biotech funds, as per an analysis of public 13F filings by whale wisdom

For example, when rates go up, banks benefit as they can charge more interest for their loans, but REITs and tech stocks suffer as the discount rate on their future earnings increases, while the estimates for those future earnings remain the same

Note that the data is volume weighted, i.e. very large funds have an overproportionate influence on the data, as opposed to the previous chart which is taking an equal weighted dataset

Morgan Stanley PB data, as of June 21st

MSXXCRWD Index for typical hedge fund longs, MSXXSHRT Index for typical hedge fund shorts