The New Role of Government

And why this cycle may evolve significantly faster than expected

In last week’s post I described how an economic downturn typically starts with weakness in housing/consumer durables, followed by lower businesses expenditure and finally layoffs. This sequence would usually take ~8-10 quarters to complete, with a broad recession under way after ~4 quarters. After that, a new upcycle ensues

There are reasons to believe this cycle might move considerably faster, with a US recession possible already this quarter. With inflation still entrenched, this throws the role of governments into the spotlight, whose actions in a downturn will decide what kind of economy we’ll face going forward, good or bad

This post walks through the reasoning for this prediction, and its implications for inflation and government decisions. As usual, it finishes with an outlook on markets

Last year’s economic boom has been nothing but stunning. However, intuitively, one might suspect the frantic pace up to be followed by an equally fast leg down. Is the intuition correct? The following three steps explain why the answer is likely yes

First - Personal income, adjusted for inflation, is now lower than before the pandemic

Because the boom rested on printed money, the economic expansion wasn’t accompanied by similar productivity gains. Thus, the inflation rate soon exceeded wage gains. People’s “real income” actually shrunk since the start of the pandemic

Looking at this chart, one might wonder, how was it possible that real GDP was up 5.7% last year? What explains the disconnect?

Second - Savings filled the gap left by lagging real income

The stimulus cheques and money saved during lockdowns provided US consumers with huge amounts of cash

These savings provided the firepower to spend in excess of real income. As a consequence, the US personal savings rate is now at its lowest level since 2013

Third - Savings are not a sustainable source of funding

Savings are our piggy bank, so we have an emotional relationship with them. If times are good, we spend them since we feel confident they will be replenished. But if times are bad, this changes, we want to save more

John Maynard Keynes called this the paradox of thrift. In a recession, the savings rate goes up as consumers feel uncomfortable about their future

Now the picture becomes clearer. If a boom is rested on savings and not real income growth, it is unsustainable

Last year, consumers were confident and spent their savings because everything went up - the stock market, house prices, the economy, etc.

Once sentiment turns, we rather save then spend as the future seems more uncertain. Demand falls back to what real income can afford. And as we can see in the first chart above, the trendline for that is much lower

Sentiment has clearly turned, but do we have any evidence for a drop-off in demand? Yes, early signs are there and growing. First, from housing:

Keep in mind the lead role of housing in the economic cycle (as discussed here and here). More signs emerged that a meaningful slowdown for housing is under way. Construction spending was up flat in March, new home sales dropped 13% and mortgage applications fell 70%. Weekly realtor.com inventory data is trending sharply up, albeit from low levels

But more so, recent developments in Canada and New Zealand likely prove instructive. These countries are a few months ahead of the US, New Zealand was the first Western nation to raise rates last year. Both housing markets had many stories about surging prices and inventory crunches just a few month ago, and both see price declines and an inventory build now. Take these two headlines from Toronto as an example:

Next, let’s look at wholesale inventory data

If demand weakens, it shows up there first, as merchants pile up unsold goods in warehouses. And this is what we can see in the chart below:

The point of inventory is important. Why?

Corporates adjusted production for artificially high demand. As that demand abates, that higher production can’t be sold and creates an inventory overhang that will weigh on future production, a “bullwhip-like” effect. The weakness in spot rates in trucking that I had mentioned before is linked to this

Finally, let’s look at corporate earnings

For corporates, this was generally a disappointing earnings season. In contrast to last quarter, many companies reported consumer resistance to price increases.

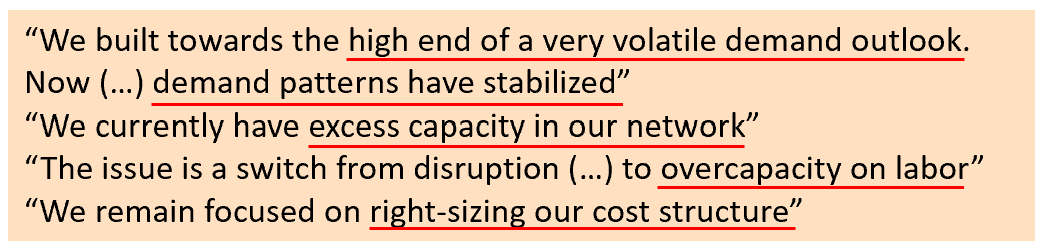

Earnings from Big Tech were particularly weak, something I had warned on multiple occasions. They have more cyclicality than the market thinks. Take these comments from Amazon’s earnings call as example, they are illustrative of the inventory dynamics mentioned above

Summary: Many signs point to a rather rapid contraction ahead. Given US GDP was negative in Q1, in technical terms1 there is a decent chance we find ourselves in a recession already by Q2

The big question is, what does that mean for inflation? Inflation can be split into two parts, goods (~25%) and services (~75%)

For goods, it is simple. Goods demand is volatile and will go down. Lower demand means lower prices. Expect goods-inflation to moderate, if not reverse

Supply bottlenecks remain, driven by China’s lockdowns and the war in Ukraine. This may create a higher floor, and in some cases even lead to further price increases. However, the inventory dynamic laid out above generally speak for downside risk to goods prices

Last week, I had mentioned the risk to commodities in such a scenario. On that, I want to follow up with a brief excursion to oil in 2008

In 2008, the oil price went up to 140$/bbl by June. In the first half of the year, the same stories were prevalent as today about commodity bull markets. But for the rest of the year, oil went down, and closed the year 72% down from its peak. The reasons: The world went into a severe recession, and as an inelastic good only a limited decline in demand was enough to create a huge decline in price

I’m not saying that we’ll see another Lehman-like crisis or that the oil price will collapse. But many investors right now are very bullish on commodities, and at the same time hold negative views on the rest of the economy. This is the current Schrödinger’s Cat of the investment world. It can’t be both at the same time. If the economy turns south, it likely drags commodity prices with it

However, the bigger part of inflation is linked to services. And services inflation is closely tied to the labor market2

The ratio of unemployed to vacancies is still historically tight, and recent data actually indicates it got worse in April3. This will take enormous length to adjust, and keep pressure on inflation for a considerable amount of time

However, there are signs that companies are changing hiring plans. Please notice Amazon’s comment on employment above. Also, the employment component of the April ISM survey was weak. My best guess is that this ratio improves first only gradually, to then see more substantial moves once businesses start to cut cost on a broad basis

Summary: US Inflation has likely seen its cycle-high, and going forward there is a chance that headline CPI data undershoots expectations. This will likely be driven by lower goods prices, while services inflation likely remains sticky for longer

So that’s it, inflation is done?

No - a recession alone does not cure inflation. Otherwise there wouldn’t be countries with persistent inflation issues, such as Brazil or Argentina

From here, it’s up to the governments to decide the path forward. In this regard, lower inflation numbers set the ground for a giant trap.

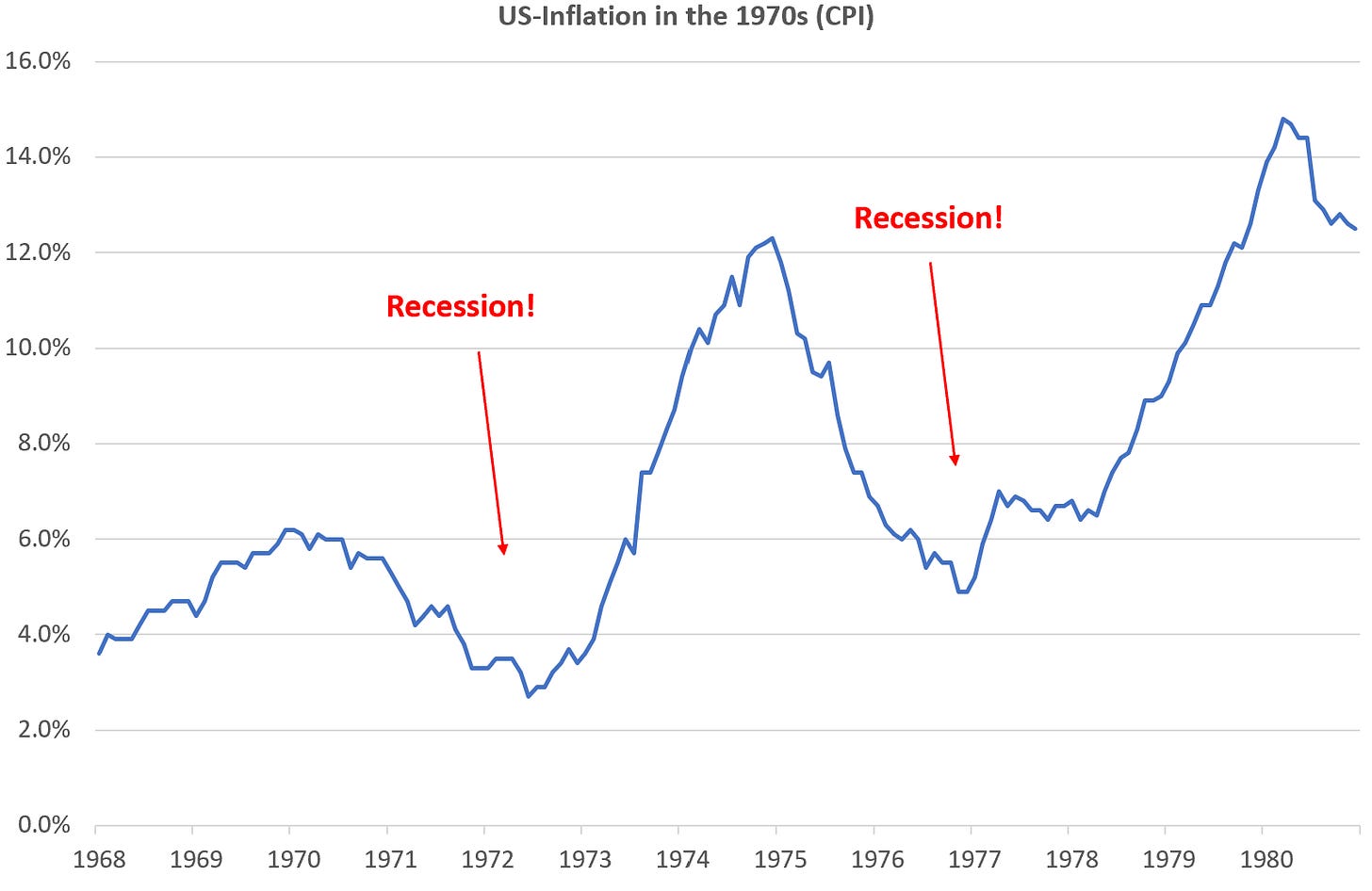

I’m repeating this chart from last week. The economy moves in cycles, and recessions reduce inflation. However, they don’t cure the economy off inflation

So what’s this trap? The answer has to do with government spending, or more precisely, to what degree will governments fund their expenditure by issuing new debt (aka “deficit spending”)

Debt is the textbook definition of newly created money, as issuing banks only have to hold a fraction of the debt as reserves. Therefore, government deficit spending in an inflationary context simply leads to more inflation - this was the mistake that perpetuated inflation in the 1970s (see chart above)

Now, like generals, governments with their spending principles usually fight the last war

After the Great Financial Crisis 2008/9 and the Euro-crisis 2011, governments focussed on austerity. This was a mistake. It aggravated deflationary tendencies and contributed to the era’s secular stagnation

Following COVID-19, governments overcorrected in the other direction. Giant stimulus programs overwhelmed the economy and created inflation

Populist movements of each time reflect this. The Tea Party movement launched in 2009 and campaigned for further budget cuts. This would have likely lead to a repeat of the Great Depression. Modern Monetary Theory came to fame in 2020 and wanted to save the economy by printing more money. We have witnessed the outcome of this experiment…

I’m not arguing that government spending per se isn’t bad or wasteful, the opposite is the case. It just depends on what the money is spent for

Governments can provide significant societal benefits in areas where the private sector falls short. These include tremendously important sectors such as education, infrastructure or healthcare which have payback timeframes that either extend over decades (too long for the private sector), where the benefits accrue beyond the originator (not an incentive for the private sector) or where a fair and equitable solution is needed

A thought-experiment at this point: Imagine if all the COVID-19 stimulus money would have been spent on those areas instead

Summary: How governments react to the next downturn will decide whether inflation turns into a long-term problem, or remains a brief, but painful episode

I believe it is likely that the US will show restrain. Whatever opinion on its leadership, the administrative body is highly professional and aware of commercial realities. I am less hopeful for Europe and the UK

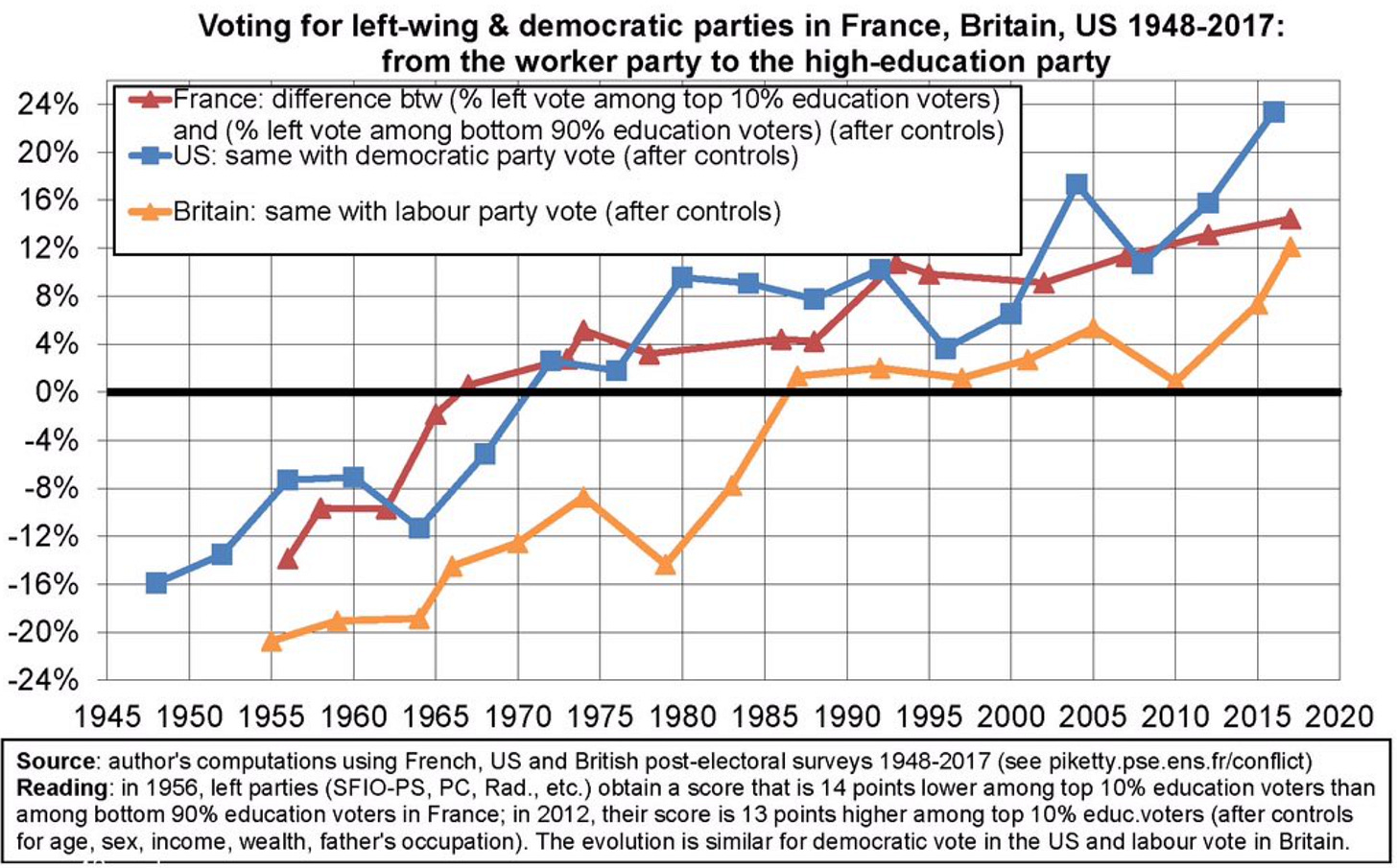

Either way, a paradigm shift back to fiscal discipline likely represents new fault lines in politics. Whether it is budget cuts or tax-raises, some part of the population will be worse-off and will fight for their representation

In the past, the absence of fiscal challenges has shifted the policy debate away from distribution to social issues. This has contributed to a much-discussed transformation in voting-patterns, from poor vs rich to uneducated vs educated. Will this shift now be reversed as the relevance of fiscal spending returns?

What does this mean for markets?

How governments and central banks react is something to watch closely over the next year. Some implications to think of:

For the Southern European countries and the UK, sovereign debt issues likely return as a theme. These can be solved via restructuring or inflation, or eventually a combination of both. For the Eurozone, this puts the Northern European countries in a awkward position with their historic aversion to inflation. It is of notice that the Swedish Riksbank took aggressive monetary tightening steps last week, a move an independent Bundesbank would have likely viewed as opportune. It is noticeable that the market now expects higher inflation for Germany than for the US over the next 10 years4

For commodity-poor Emerging Markets, the current situation creates unprecedent challenges. Food shortages, high commodity prices, a very strong US Dollar and potentially a global recession will likely lead to defaults and conflict

The source of the strong US Dollar is higher yield on US government debt, which begs the question whether US bonds are attractive now. I am warming up to this idea, however as long as there is no clear outline on the path of the US deficit, I still feel the risks are not clear yet

With regards to equities…

I continue to see poor risk-reward for equity markets, in particular, but not exclusively for the Nasdaq-100, Luxury and Homebuilders (XHB). The risk of bear-market rallies has risen with exceptionally poor sentiment, but I don’t believe the Fed will relent on its aggressive stance in the near term as long as public opinion cares more about inflation than declining markets, and April’s inflation data is likely still uncomfortably strong

To be clear, I don’t think we’re there yet, but whenever the Fed declares a “mission-accomplished” and relents from its hawkish stance, whether premature or not, a rally in secular growth sectors likely ensues. These benefit from more certainty on interest rates and are less impacted by a cyclical slowdown. Historically, high-growth tech would be the best sector to play this, however this area is still plagued by the fallout from the bubble (e.g. last quarter Robin Hood issued $220m stock based compensation on $299m revenues, how is that sustainable?). Established software (ETF:IGV) seems a good play when that time comes

Please note: A recession requires two quarters of consecutive negative GDP growth. US Q1 GDP was -1.4%, however the main negative component was a worsening of the import/export balance, while consumer expenditure remained strong

The biggest part of services inflation is rents, which drive inflation with a ~ 1-year lag. So last year’s rent increase will continue to show in CPI until the end of the year. Current rent increases have slowed somewhat in April, but remain on a upwards trajectory

The April JOLTS survey reported a 200k increase in vacancies to 11.5m in April, and a record 4.5m quits. Unemployment data for this coming Friday will likely show a further decline in unemployment

Germany 10-Year Breakeven at 2.95% vs US 2.85% as per Bloomberg