The Plight of the UK

A cautionary tale

Over the past days, several news caused much turmoil in financial markets. Readers of the Next Economy were prepared, as recent posts highlighted these risks. In particular:

Crypto-lender Celsius halted withdrawals following a severe price decline in Crypto assets over the weekend - likely an intermediary step towards bankruptcy. With $17bn in assets and 1.7 Million customers, Celsius is comparable to a mid-sized bank, just without FDIC insurance. Further, Crypto exchange Binance temporarily halted withdrawals. I pointed out the risk at both Celsius and Binance in the recent post “On Crypto”, as well as the downside in Ethereum, which has since sold off by 40% since

US inflation data came out stronger than expected this past Friday, leading to a upwards repricing of bond yields and a sharp sell off in equities. I had discussed this as likely scenario last week in “3% is Not Enough”. As usual, I will share more market views at the end of this post, and explain why I remain short despite the market drawdown

Leaving Crypto and Inflation for now, today’s post turns to the United Kingdom, my home for the past 17 years. The country has many great things going for it, and its capital London remains one of the few true global cities - some even say the last one in an age of national withdrawal. However, recently things have not gone so well for the UK. This post shines a light on the underlying reasons, and what lessons can be drawn for others

While times are tumultuous everywhere, the United Kingdom seems to stand out amongst its Western peers. Recent newspaper headlines are dramatic:

Financial data reflects the sentiment. UK inflation expectations for the next decade track significantly higher vs its peers, and over the past year, the Pound has lost 15% against the US Dollar:

What’s going on?

To answer this, we have to take a few steps back. Let’s start with the year 2005 and a comment made by then prime minister Tony Blair:

He could not have been more wrong. A debate about the effects of globalisation would have been much needed. Yes, it brought great benefits, but these were distributed very unevenly:

In Emerging Markets, millions were lifted out of poverty as they joined the global labor pool. In the West, it was corporations and asset owners who benefited. Global labor competition kept wages low and costs down. Revenues increased with access to foreign markets

The loser was the Western middle class. Their real wages stagnated. This created sluggish domestic demand, which central banks fought with lower interest rates and Quantitative Easing. This did little to actually stimulate demand, but it did drive up asset prices and increase inequality

As a result, many in the West were angry, and expressed their anger at the polls

In the US, the discontent lead to the election of Donald Trump in 2016 - a slap in the face of both the Democrat and Republican establishment

The same year, the British public voted to leave the EU. The swing vote was cast in the working-class districts of Northern England, also called the “Red Wall” for its strong historical loyalty to the Labour Party

In Brexit’s wake, political turmoil followed

Prime-minister David Cameron resigned. He was followed by the pragmatic, yet uncharismatic Theresa May. Her attempt to square the circle of fulfilling Brexit and keeping EU membership benefits lead to a convoluted message and painfully drawn-out negotiations with the EU

The stalemate was solved by this man - Boris Johnson

His carefully curated, unkempt image is often met with disbelief abroad. Yet Boris Johnson speaks a language ordinary people can relate to, he is a populist in the true sense of the word

He understood that the public was tired of lengthy negotiations. He equally understood the energising dynamic of national pride and direction. He also understood the social friction and discontent in many working-class counties

So he translated all this into a “Hard Brexit”, a clean cut with the EU and an exit from its Single Market. This would let the UK forge its own destiny, with independent free trade agreements around the world. In addition, he promised to “level up” the parts of the UK that had been left behind by globalisation

As a result, he won the 2019 election with a landslide. In particular, he conquered Northern England’s working class “Red Wall”

His blend of national appeal and social support programs has a historical analogue in Latin America - Peronsim.

Established by Juan Peron in the 1950s Argentina, this style of politics contributed to decades of boom and bust across Latin America

And today, six years after the pivotal vote, the results of “Hard Brexit” take visible shape. They resemble Latin America’s experienced with many Peronist experiments - an inflationary economy, challenged for growth

Four drivers contributed to this, in particular:

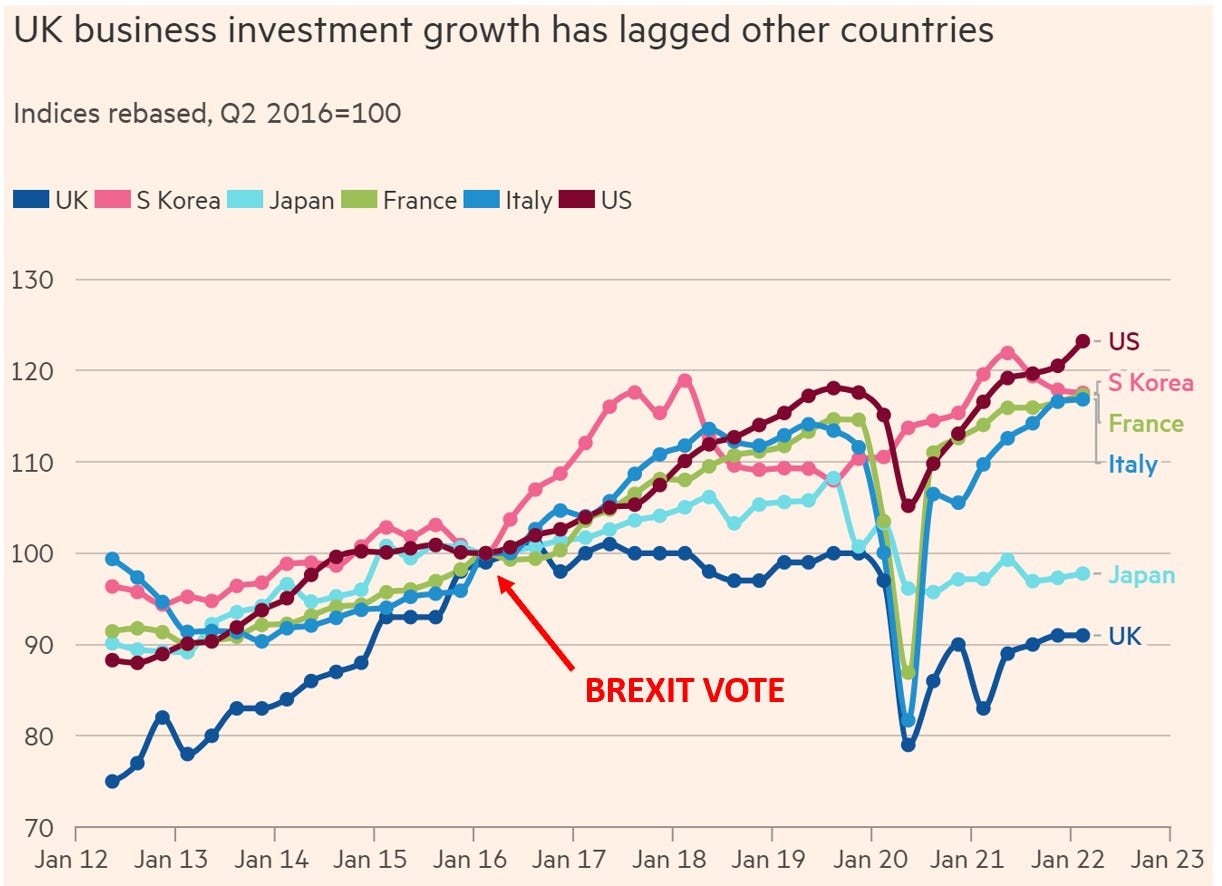

1- Business investment into the UK slowed dramatically

The head of the CBI, the UK’s industrial body, recently summarised the effects on business of the isolationist stance: “We are seeing global companies saying the UK is not a good place to invest right”. Data confirms this statement:

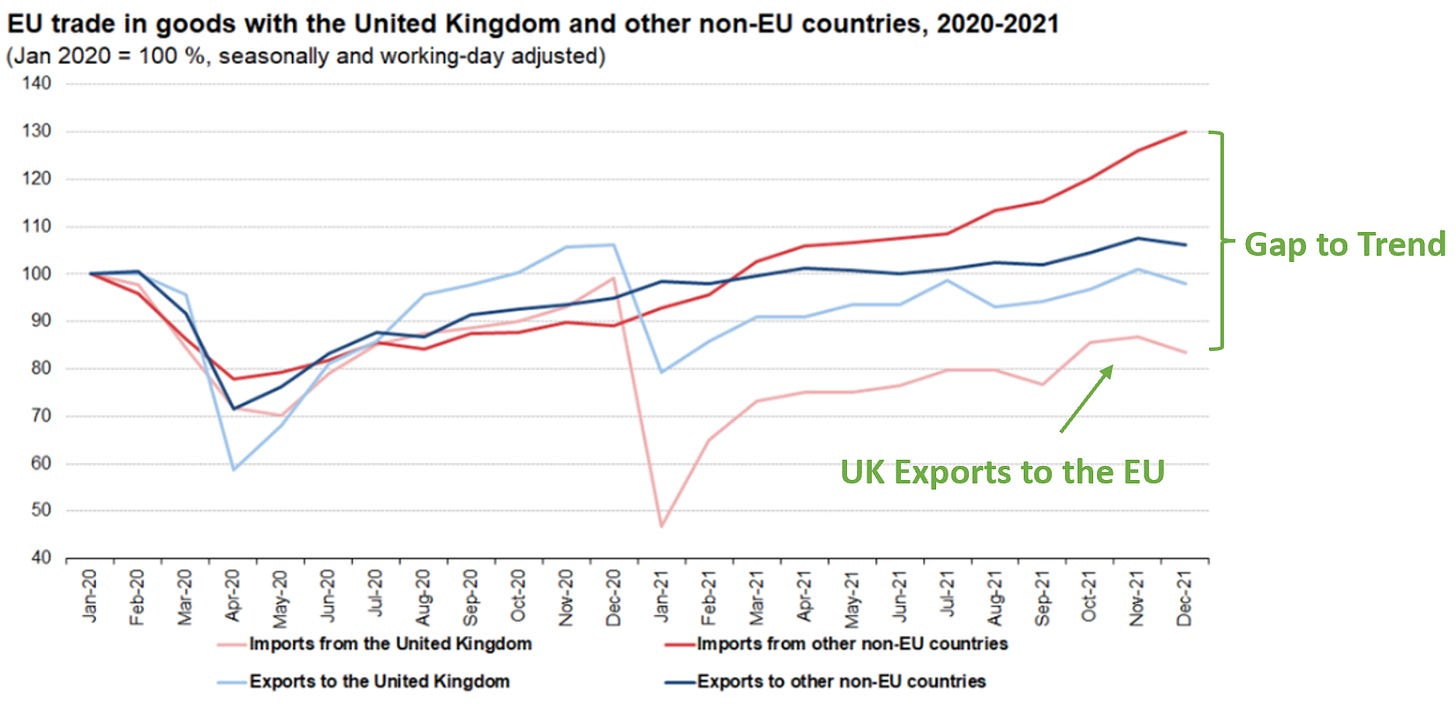

2- Trade with Europe has declined, in particular exports

The EU is the UK’s biggest trade partner (42% of exports, 50% of imports). Tariffs, checks and increased bureaucracy have slowed both, but in particular UK exports to the EU. They are ~40% lower vs. their previous trend1

3- The labor market misses skilled talent

For decades, the UK balanced deficits in broad secondary and tertiary skills-based education (e.g. apprenticeships) with immigration from Europe, from the Polish plumber to the Italian nurse. Immigration from Europe has slowed down considerably

Immigration from Non-EU countries (e.g. India, Nigeria, Philippines) remains high, but their education standards are often lower. This requires additional investments to bring them in line with local standards

4- Historically, the UK is prone to deficit spending

As elaborated in prior posts, deficit spending into an inflationary economy amplifies inflation as debt is newly created money

What do all of these dynamics have in common? They weaken the currency, and they are highly inflationary

This brings us back to the two charts at the beginning of the post - the decline in the British Pound, and the market’s high inflation expectations

As the pound weakens, energy and food imports which are denominated in foreign currency become more costly. This in turn increases inflation further

As a result, the average UK household energy bill will reach £2’800 this year, up from £1’250 in 2021. With a median household income of £31’400, this is an unbearable situation. The government has responded to this with a £21bn subsidy program and a windfall tax on oil & gas profits

In an irony of history, it is the Labour party now who warns on the inflationary risks from the subsidy program:

Conclusion: The UK provides a painful case study for what awaits those who reverse openness and trade between nations - higher inflation and more pain for the masses. It also reminds us of the potential path the populace chooses if said openness leaves too many behind

The fault is on both sides of political spectrum. Labour, just as the Democrats in the US, did not listen to the many that screamed at them that globalisation made their lives worse (“Deplorables”). The Tories ignored all economic reason and lead the UK down Latin America’s path of Peronism, with the consequences visible already now

On that note, Brexit remains an emotional topic, as does the European Union with all its faults

These will likely once again be exposed, starting with the incredible bubble in German Real Estate which was fuelled by negative ECB interest rates

But whatever one thinks of the EU, two advantages remain undeniable. The small region of Northern Ireland, torn between the EU and the UK, illustrates them well:

First, Peace: European countries have been at war with another for 2000 years, and the worst war of all is only two generations in the past. The Ukraine war shows how quickly atrocities return that we thought long forgotten. And in Northern Ireland, which has a long bloody history of sectarian conflict, tensions resurfaced pretty much the same moment the UK left the EU

Second, the Single Market: The EU’s Single Market provides access to 500m consumers. It is the world’s biggest market after the US, and the absence of internal trade hurdles is a hugely valuable asset to the 25m companies that participate in it. Following the 2019 Brexit agreement, the Northern Irish economy remains part of the Single Market. In a reflection of its value, it has fared much better since than the rest of the UK, despite being historically one its the most deprived regions

What does this mean for markets?

The UK’s above average inflation pressures, together with a history of deficit spending and currency debasement make the British Pound likely not a good store of value for the foreseeable future

Neither seems the Euro, to be frank. I would think it likely that cash balances fare better in US Dollars, Swiss Francs or Gold over the medium term

Equally, businesses solely focussed on the UK domestic market, from Retail to Homebuilders, likely face a very challenging path ahead

With regards to the broader market, my view remains the same. Significant downside remains on pretty much anything from here:

Many lead indicators point to an economic contraction that may be harsher and more sudden than many think, which means significant downside to corporate margins and earnings estimates following a period of significant malinvestment Please see my economic cycle framework in “Consumer Cycle, not Business Cycle” and the post “The New Role of Government” for more context, in particular the role of Housing as first “domino to fall”

At the same time, as predicted last week, the Fed is stepping up its actions in response to poor inflation data, as well as rising consumer inflation expectations. A 75bps rate increase as this week’s FOMC meeting has now been leaked to the press. I do not think of this as clearing event for equities, to the contrary

With all that in mind, I’m hard pressed to come up with a more negative context for risk assets. I continue to find 1974 the best historical analogy for this bear market - a rather rapid descend

For those reasons, I remain short many sectors, including Homebuilders (XHB), US Airlines (JETS), DAX, Materials (XLB), Metals & Mining (XME/SXPP), Bonds (TLT), Ethereum and Nasdaq, with the only small long in front-end crude oil futures (WTI)

Over the past week, I’ve added European Banks (SX7P) as proxy for the likely looming distressed debt cycle as well as bubble risks especially in German Real Estate. I’ve also added shorts in semiconductors (SMH). It seems likely to me that as durable goods demand evaporate, we’ll see a semis inventory glut, further exacerbated by double ordering (see recent auto-industry comments on alleviating chip-pressures)

Please keep in mind, I could very well be wrong, and many unexpected turns can occur. For this, whenever I initiate a position, I define the stop-loss at which I would exit again, and I pull these stop-losses up should the trade be profitable

I’ve received a fair amount of push back on my view on metals and mining (XME, SXPP). And yes, the 1970s were a long commodity bull market, but in 1974 copper fell -40%. And I agree, it seems that oil and coal give up last, and their cycle lows might be much lower with the lack of investments in them. Either way, they are tied to power and transport, while many other commodities are tied to the much more cyclical demand in durable goods, which as discussed is falling off a cliff

For guidance, I am watching VIX >40, 10-year real rates ~1% , as well as a reversion in US 5/10 year inflation expectations. The former likely denotes short-term capitulation, the latter two likely stabilise equities near term, and make bonds an attractive investment, as well as its equity long-duration equivalents (High-Growth Tech)

In any eventual relief rally, the fastest horse to me seems Energy (XLE, OIH, SXEP). Oil equities are currently sold off with the market, while the Oil Price remains firm, so I’m preparing for that

If bond yields stabilise, I would also return to High-Growth Tech which is once again under pressure. This includes Biotech (XBI), Software (IGV) and Solar (TAN)

For anyone who prefers to take a less active stance, I can only repeat like a broken clock - Cash is King. I may be wrong, but in my view we’re not near the moment where the tide turns, and this includes most asset categories. A look at Canada’s Real Estate market, which seems ~3-6 months ahead of the US, may proof instructive and ominous in that regard:

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!