The Three Blind Spots

The paradigm has shifted, but most are stuck in an old regime

In January ‘22 I wrote a post called The Blind Spot, forecasting a world where interest rates would stay “higher for longer”. Back then, this catchphrase had not been coined yet and the US Treasury 10-year rate was at 1.7%. I now see three blind spots again, which -in my view- are of equally enormous relevance for the direction of the US economy, and with it asset markets

We are likely in the middle of a paradigm shift that old frameworks won’t catch. Yet, the market is already grasping its vague outlines, as I laid out in last week’s post “The Trillion Dollar Question” - please read it if you missed it, it complements today’s post in important parts

The story of this decade is likely fiscal policy, which has entirely changed and for which few experts are around. This is in contrast to monetary policy which appears to have become toothless, yet remains a field dense with expert views

As US bank lending turns up, we likely enter a unique historic situation where both fiscal and bank lending flows are expansionary, instead of alternating as in the historic precedent, when high budget deficits aimed to balance contracting credit. The implications on the financial world will be profound, with a panic-bid for US value assets possibly on the horizon as the market comes around to what I outline today

As always, the post closes with a current outlook on markets. I continue to expect a window of weakness for September and October, and continue to prepare to go long whatever has the highest beta to the view outlined today, should said window occur

So what are the three blind spots that everyone is missing? Let’s jump right in:

Monetary policy works very differently in a world awash with liquidity. In fact, it is likely still stimulative

Following the Great Financial Crisis, the US undertook much effort to make its economy resilient against interest rate hikes:

Most importantly, consumer residential mortgages were given 30 years duration and a fixed interest rate. This neutered the most important interest rate hike transmission channel to consumers, as mortgages represent ~80% of consumer debt

Then, Covid-19 followed, interest rates were cut to 0% and the long end of the yield curve supressed via QE. Households and corporates refinanced their existing debt, locking in low rates, and as the long end was suppressed, for an extended period of time

The stunning consequence, take US corporates as an example: In ‘23, they will have ~$100bn less net interest expense than the year before, despite the higher rates (!). Why? They get paid 5.5% now on their vast cash holdings which mushroomed during Covid, while their debt cost will take many years to reset

The tailwind of high interest income for the private sector is set to grow further as 31% of the existing government debt stock refinances next year - contrary to household and corporate debt, it had never been termed out

With >100% government debt/GDP, the US has a huge stock of obligations outstanding. As it rolls over, every month more interest payments are wired from the government to the private sector, to the tune of $1.3tr, or ~5% of GDP next year (!). And neither Democrats nor Republicans are in any rush to cut the budget elsewhere to balance this outflow

But this is not the only stimulative channel. There is another one, poorly understood yet very significant - interest paid by the Fed to banks on their reserves (IORB)

Since the GFC, the Fed pays banks interest on their c. $3.3tr reserves. At 5.5%, they receive ~$170bn annually, which like any other unencumbered cash income they can lever 10-20x to create or buy loans and other assets - a hugely stimulative and entirely unnecessary subsidy to US commercial banks (cf. this good essay by George Robertson for details)

While there will certainly be many individual cases where the high interest cost hurts some, on aggregate US households and corporate are currently positively geared to higher rates - yes, it is mind bending, but that’s what the data tells us

Rates would likely have to be significantly higher for the damage on those exposed to rates to outweigh the tailwind for the vast majority that had been immunised to them. The better tool - in my view - is likely QT, just as after WWII (see previous post here on details)

Summary: Contrary to common wisdom, US monetary policy is likely still stimulative in its current stance. Households and corporates are positively geared to higher rates, and interest on reserves flows back into the economy with leverage

The US is now a war economy

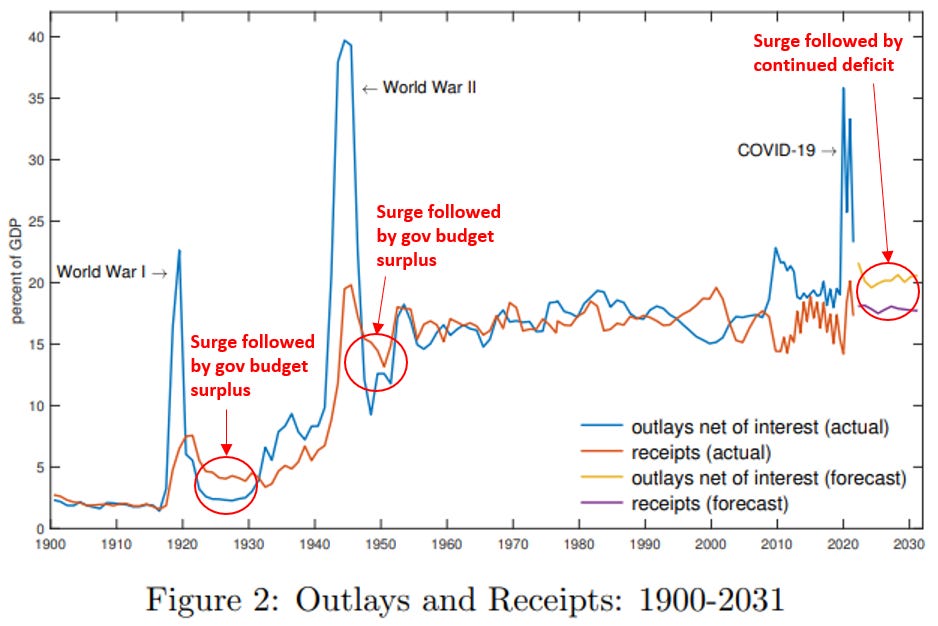

The US fiscal stimulus post Covid-19 is unprecedented and only comparable with the two war-time economies WWI & WWII

As laid out in “On Reflexivity”, while the “War on Covid” was the trigger, this fiscal deficit bonanza has to be seen as a forceful response to the 2010s secular stagnation, which brough high inequality and social discontent

Further, as per the chart above, note that the WWI and WWII deficits were followed by a consolidation period during which the government ran a surplus. Today, the opposite is the case, a high deficit is bound to continue for the coming years

So now, every quarter, billions of US Dollars are pumped into the US economy. Very importantly, unlike QE, this money goes into the real economy, and not into the reserves account of JP Morgan. The chart below plots the US net daily fiscal flows, i.e. the money the government sends to the private sector minus the taxes it collects from it. It is easy to spot the dramatic contrast to the pre-Covid period

The rampant deficit will ensure that money supply continues to grow, and indeed we can already see that M2 has turned up again1, after having consolidated since the launch of QT in Spring ‘22

Summary: The ongoing US deficit spend is comparable only to war-time economies, and so far no end is in sight. This puts fiscal policy firmly in the driver’s seat, a massive paradigm shift after decades of monetary policy dominance

Despite current high rates, bank lending is bound to grow again

Let’s recall - there are two ways an economy can create new money:

Fiscal deficit spending, which creates new private sector deposits

Banks issuing new loans, which also creates new private sector deposits

Historically, these two alternated - fiscal expanded when the economy went into recession. In those moments, bank lending typically contracted, such as during the GFC. Vice versa, fiscal would contract in boom times when bank lending expanded, think of Clinton’s budget surplus during the New Economy bubble

Now, because of high rates, everyone is expecting bank lending to contract, such as Apollo’s Torsten Slok here

But if we put 1. + 2. above together, i.e. monetary policy behind the curve, and continued huge fiscal flows to the economy, of course there is an incentive for credit to grow - even at current rates

Simply put, if nominal GDP grows at 6-9%, then loans at 5%+x are a pretty good deal. And that’s what we are seeing - bank lending has picked up again (!)

This is also visible if we look at the monthly growth rate, which has inflected upwards

And it ties in with yesterday’s NFIB Small Business survey which shows that lending conditions have improved again, back to historic norm

Summary: US bank lending is inflecting upwards. This creates a unique historic situation where both fiscal and bank flows are materially positive. In other words, the two engines of money creation will now fire simultaneously, instead of alternating as historically the case

So let’s synthesise these three findings

Monetary policy is likely too loose

Fiscal flows are unprecedented and set to continue

Bank flows are likely to pick up again, adding to fiscal flows

Let’s then recall what the market is subtly telling us, as I spelled out last week in “The Trillion Dollar Question”

It continues to prefer equities over bonds (see below S&P 500 vs TLT), implying that bottom-up nominal earnings expectations are rising faster than the drag on the valuation multiple from higher bond yields

Finally, let’s add to that the US goods economy appears to have hit an inflection point, with many signs pointing to a cyclical upturn, as I’ve laid out in several posts

Taken together, what does all of this mean?

The massive fiscal flows and now turning bank flows likely lead to significantly higher nominal and possibly higher real US economic growth than investors currently anticipate

Once investors come around to the views spelled out today (and of course, should these be right), it would be logical for an aggressive bid to ensue for any assets that are sensitive to these higher growth expectations, and insensitive to higher bond yields

It seems hard to see a recession for the US, if both fiscal and bank flows pump hundreds of billions of new US Dollars into the economy every quarter. It seems much more plausible for that to occur when at least one of these two streams ebbs (not in sight)

But with these high nominal flows, doesn’t it mean that inflation will come back soon? Likely yes, but the timing and degree may vary:

The optimistic view is that goods capacity expanded over Covid so production has room to run before it becomes inflationary. Productivity gains are realised as staff hired since Covid gets fluid in their new jobs. Spare capacity in oil is brought back on. The massive growth in multi-family homes keeps a lid on US rental growth, ample immigration lowers wage pressures

The pessimistic view is that the high share of government spend distorts the economy towards unproductive activities, Saudi continues to use oil as geopolitical weapon, commodity prices rise quickly as hamstrung supply cannot keep up with demand, wage growth remains high even as unemployment rises as skilled immigration is shut out (cf. UK)

I am personally optimistic, or at least I would expect a sequence of the optimistic case first, followed by troubling stagflation only several years down the line. Why?

The decade of secular stagnation possibly provides ample runway until a fiscally dominant approach reaches its limitation. We might see a period strong of both strong real and nominal growth first, similar to Roosevelt’s New Deal that fixed the Great Depression legacy

However, in the long run, there is no doubt that a highly expansive government sector lowers productivity and eventually leads to inferior economic outcomes

Time will tell, and energy likely plays a critical role in deciding the path forward

Oil prices are spiking, and if they meaningfully exceed levels similar to the Ukraine war, it will create a drag on the world economy ($90/bbl crude now, ~$120 in June ‘22). Nominal growth would stay high, but real growth would suffer

Yet, as mentioned, there is still plenty of Oil spare capacity withheld by OPEC from the market. Does OPEC want to release that if/as price spike? Can discipline be maintained across all its members? Will US shale ramp up in time if prices stay high? The sequence of events here will be political and unpredictable

Conclusion:

Unprecedented fiscal spending now likely coincides with rising bank lending - a historic anomaly

These immense combined money flows likely support fundamentally higher nominal, and possibly higher real US economic growth, the outlines of which markets already draw today

Monetary policy so far has not made any difference to this trajectory, and it appears unlikely that it would any time in the near future

What does this mean for markets?

The following section is for professional investors only. It reflects my own views in a strictly personal capacity and is shared with other likeminded investors for the exchange of views and informational purposes only. Please see the disclaimer at the bottom for more details and always note, I may be entirely wrong, may change my mind at any time and this is not investment advice, please do your own due diligence

My plan remains the same:

I sit with high cash, a China Tech long, some energy and a EU hedge. I will raise more cash into Opex this Friday, and continue to expect September/October to be wobbly, as the liquidity picture for that period is adverse due to large corporate taxes due

Should the wobble materialise, I intend to go max long whatever has the most fitting exposure to the following list of criteria (1) beneficiary of US domestic nominal growth, (2) low valuation = low sensitivity to bond yields, (3) low exposure to labor costs (4) low regulation risk/regulation beneficiary and (5) low positioning. I see the “risk” of a panic-bid into these areas as real in light of what I have laid out today

I am still working through the list of sectors and businesses that fit this bill, but US value/small caps, US domestic industrials as well as some commodities certainly come to mind, but also some monopoly-like Tech businesses with moderate valuation

As mentioned last week, a period of higher real rates would have profound implications for the asset management industry - e.g. who needs hedge funds churning out 5% per year if US Treasuries eventually pay 7% nominal and 3% real?

More so, most allocators would have their assets assigned to the wrong areas, as the investment management world is generally still long QE beneficiaries (real estate, gold, large caps, unprofitable Tech) and thus implicitly or explicitly short real economic growth beneficiaries (value, oil, industrial assets, small caps)

However, historically, war economies coincided with periods of low or even negative real rates. This was primarily a way for the government to pay its bond obligations

Yet, history rhymes, but does not repeat. With Reflexivity in mind, we just had 15 years of very low real rates (see chart below with the Oct ‘21 trough *before* the war time economy), so maybe this time we get something else

I remain open-minded on this crucial topic, will continue my research and share my findings here with you

Thank you for reading my work, it makes my day. It is free, so if you find it useful, please share it!

DISCLAIMER:

The information contained in the material on this website article is for professional investors only and for educational purposes only. It reflects only the views of its author (Florian Kronawitter) in a strictly personal capacity and do not reflect the views of White Square Capital LLP and/or Sophia Group LLP. This website article is only for information purposes, and it is not intended to be, nor should it be construed or used as, investment, tax or legal advice, any recommendation or opinion regarding the appropriateness or suitability of any investment or strategy, or an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, an interest in any security, including an interest in any private fund or account or any other private fund or account advised by White Square Capital LLP, Sophia Group LLP or any of its affiliates. Nothing on this website article should be taken as a recommendation or endorsement of a particular investment, adviser or other service or product or to any material submitted by third parties or linked to from this website. Nor should anything on this website article be taken as an invitation or inducement to engage in investment activities. In addition, we do not offer any advice regarding the nature, potential value or suitability of any particular investment, security or investment strategy and the information provided is not tailored to any individual requirements.

The content of this website article does not constitute investment advice and you should not rely on any material on this website article to make (or refrain from making) any decision or take (or refrain from taking) any action.

The investments and services mentioned on this article website may not be suitable for you. If advice is required you should contact your own Independent Financial Adviser.

The information in this article website is intended to inform and educate readers and the wider community. No representation is made that any of the views and opinions expressed by the author will be achieved, in whole or in part. This information is as of the date indicated, is not complete and is subject to change. Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although believed to be reliable, has not been independently verified. The author is not responsible for errors or omissions from these sources. No representation is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of information and the author assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise such information. At the time of writing, the author, or a family member of the author, may hold a significant long or short financial interest in any of securities, issuers and/or sectors discussed. This should not be taken as a recommendation by the author to invest (or refrain from investing) in any securities, issuers and/or sectors, and the author may trade in and out of this position without notice.

I appreciate that M2 is a flawed concept for many reasons, e.g. adjustments could be made to exclude dormant excess reserves that piled up under QE. Either way, this snapshot shows a upward direction of travel in “money”

Another great piece, Florian! I've been an avid follower of your content and admire your process and framework. I largely agree with your thesis and it's associated knock-on effects.

A couple of thoughts, perhaps just to play devil's advocate:

1) For all her alleged faults, one of America's great strengths IMO remains its largely democratic system and freedom of expression. It wouldn't be too much of a stretch to imagine a reflexive process where a continued rise in treasury yields puts intolerable pressure on the US government, thus putting the U.S. fiscal state front and center of the public eye. Would the rhetoric then shift towards taking steps to put the U.S. on a more sustainable fiscal path? Admittedly, as Churchill once said that the Americans will always do the right thing, only after they have tried everything else. So the U.S. might have to go to the brink before practical action is taken. That may come in the form of tax and healthcare reform, budget process reform and national security solutions that involve trade-offs.

2) While I agree that IORB and fiscal liquidity leave bank flushed with cash and ample room to make loans, that addresses only the supply side of the equation. Pre-COVID, banks were similarly in prime position to make loans but tepid demand for loans translated to a disappointing decade of economic growth. Though it's true that most large firms had termed out their loans at low rates post-COVID, small and medium firms seem to be feeling the negative effects of rising cost of funds disproportionately. The SLOOS also indicates a continued decline in the net percentage of firms reporting stronger demand for C&I loans. That said, there has also been an uptick for the consumer loans category. So I'm less sure about the growth path going forward.

3) While things appear relatively rosy at the moment, I'm concerned the major components of U.S. household net worth such as home equity and retirement accounts could come under pressure if the labor market weakens much more in 2024. Job losses may led to forced selling of homes previously tied to low mortgage rates and create cascading effects on economic growth, especially the cyclical areas. That's all very hypothetical and certainly not what I'm projecting. Just thinking out loud about the stability of the collateral backing the household net worth figure. Cheers!

You're certainly an independent thinker. We live in interesting times!