The Wile E. Coyote Moment is Coming

As consumer excess savings run out, the US economy is bound to hit a painful wall

In the Looney Tunes assembly of cartoon characters, Wile E. Coyote plays the role of the hapless desert dog that runs mindlessly over cliff edges, to then suddenly fall from mid-air upon realising where it is

I believe a similar moment is coming for the US economy - in other words, a sudden, unexpected activity decline that will likely represent a formidable challenge for the nation’s institutions, in particular the Fed

Now, one needs to be very careful with predictions of economic calamities. They often make an intriguing read but occur very seldomly, as it is in everyone’s interest to avoid them, for good reason. Cognizant of that, it is nevertheless what the data tells me, as I lay out in today’s post. It includes some pertinent findings with regards to inequality. I also spell out where I think I could be wrong

As always, the post concludes with a current view on markets. I’ve previously discussed how I believe 2023 to be a year for bonds, and how I was patiently waiting for a sell-off in US Treasuries to establish a position with good margin of safety. This moment has likely now arrived, and I’ve put capital to work in long-term US government bonds

Why is the US economy facing a sudden, Wile-E Coyote-like drop in activity?

Here is the 20-second summary: US consumers currently spend more than they make, and finance this spending out of savings. Once these savings are depleted, they need cut back, setting off a domino effect across a very fragile US economy- the Wile E. Coyote moment

Let’s look at it in detail, how did we get here?

The US printed several trillion dollars to support the economy during Covid-19. The assumption was that the pandemic would cause a depression like in ‘08/’09. However, it turned out that the economic scars where much smaller

The printed money ended up in households’ checking accounts and, once the country reopened, created a demand boom. Prices went up significantly in response. Wages however did not keep pace, as productive capacity did not increase. After all, the new money was not owed to a productivity wonder, but to the printing press

As a result, Americans’ “real income” decreased. In other words, after accounting for inflation, consumers had less income in their pocket than pre-pandemic

Spending however, to this day, continues above a pre-pandemic pace, with the difference financed by stimulus savings. For obvious reasons, this is not sustainable

At some point the savings run out. When is that? Excess savings can only be estimated, e.g., by comparing how much consumers have recently saved of their income (3-4%) vs what they used to save pre-pandemic (7-8%), amongst other assumptions. The economics teams of the various Wall Street banks have run these numbers and put that moment between the middle (JPMorgan) and the end of 2023 (GS)

Now, as I allude to above, “excess savings” is loosely defined and conclusions vary materially depending on the assumptions. For that reason, my team and I have dug deeper to triangulate any conclusions

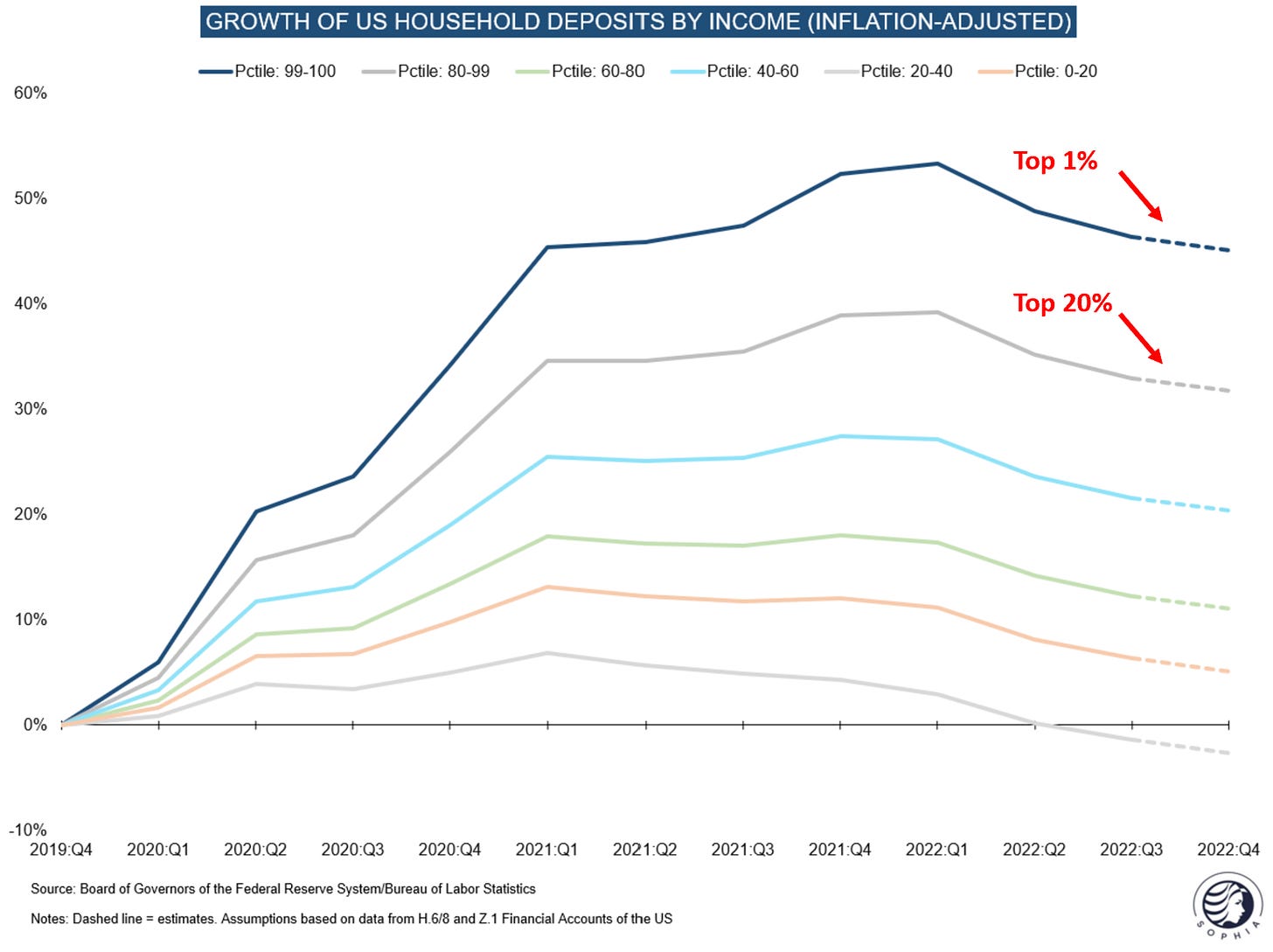

For this we looked at the household balance sheet composition, split by income quintile, as the Z.1 Financial Accounts of the US and the Distributional Financial Account provide it. The analysis revealed further findings, with some important conclusions in particular for inequality

To start, we simply compared household deposit levels today vs before the pandemic (Q4 ‘19). We’re interested in how far these deposits go for consumption purposes, for which reason we adjusted them for the 15% inflation that has occurred since, “real deposits” so to speak

Looking at the chart, it stands out that in real terms, the lower income demographics are on track to revert to their pre-pandemic state, or are already there

The top 1% and top 20% are still comfortably above

Here’s what’s important: Just looking at the cash levels gives an incomplete picture. We also need to include the other side of the balance sheet, in particular how household debt has evolved (i.e. mortgages, auto loans or credit card balances)

If we assess the evolution of their deposit and debt position in aggregate, the picture appears significantly worse

The difference between the various income brackets is glaring, and my bet is that at the end of all this many political questions will be asked. The top 20% and the top 1% are much better off than pre-pandemic, all other groups are now in fact worse off

In order to keep pace, they have taken on more debt, so their mortgages, auto loans and credit card balances grew. This is particularly pertinent as with rising interest rates these debts become much more expensive

Summary: Excess savings are running low for US consumers. Aggregate data hides substantial computational differences. The aggregate financial position of most groups is already significantly worse off than pre-Covid, while the top 20% and top 1% still sit on very comfortable cash cushions. Either way, the current spending pace is unsustainable and over the coming quarters likely drops off as savings are depleted and/or debt is maxed out

But how does the likely decline in consumer spending cascade into a domino effect that substantially slows the economy? Here’s how I assume it unfolds:

You may recall from previous posts how especially manufacturing businesses struggle with a trifecta of headwinds (lower demand, too high inventories, too high cost of capital). At its root is the demand brought forward during Covid (how many new TVs does one need?)

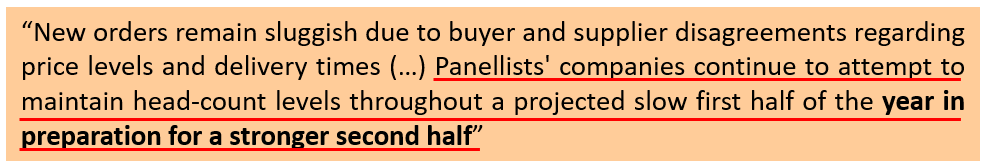

This has resulted in significant overstaffing. Currently, these businesses are hoarding labor as they hope for a 2H recovery

Please recall, layoffs in the highly cyclical manufacturing industries were historically enough to materially drive up unemployment

If US consumer demand falters as laid out above, these recovery hopes turn out to be misplaced. Then, a dam bursts where layoffs quickly increase as companies try to protect margins, which are already severely under pressure

A domino effect ensues: Lower consumer spend → lower corporate revenues → more layoffs → lower consumer income → lower corporate revenues → more layoffs etc.

Please keep in mind, in an environment of weak consumer demand, companies historically responded with price cuts. This is why I expect a inflation-deflation yo-yo, as was the case following WWII (see here), with deflationary CPI prints possible in 2H ‘23

When that Wile E. Coyote moment comes, the economy will desperately need more money. Many levered companies likely encounter cash-flow issues. But it will be in particular consumers (outside the top 20%), who need new cash to increase or maintain their spending. However, there are three big issues at hand

First - the Fed is still firmly in the inflation-fighting mindset and has historically shown little agility in changing its course (cf. ‘21 when inflation was deemed “transitory” for too long). It will likely take much time for them to turn to what may become a very different reality

Second - Even then, given the structural changes to the economy, from tight commodities to the demographic cliff, a very aggressive monetary response may indeed risk bringing inflation back quickly

Third - Consumers may have become desensitised to interest rate cuts. Most of their mortgages have been refinanced at rock bottom rates during Covid. So the refinancing trick, where a new mortgages and/or home equity is taken out at lower rate, will be hard to repeat

Summary: A slowdown in consumer spend will likely break the dam of hoarded labor, as companies give up on an H2 ‘23 recovery. This sets a negative feedback loop in motion, where higher unemployment leads to lower aggregate demand and more cost cuts

The scenario I lay out above has substantial consequences for the US economy. So I need to ask myself - where could I be wrong? The following arguments come to mind:

Consumers could take out more credit to replenish lost savings. This could tide the economy over until the cycle accelerates again

Inflation comes down while wages keep growing. This increases excess savings

Rather than a domino-effect that creates a sudden drop off, things slow gradually, with plenty of time for politics to intervene

Government stimulus programs such as the Inflation Recovery Act (IRA) or Infrastructure Act compensate for the decline in excess savings

China’s reopen will stimulate the world economy

With a 5% interest rate, savings provide a healthy income. This helps them grow

Often in economics, the awareness of an issue prevents it from occurring. Politics can still act to avoid the described outcome

And these are my counterarguments for each:

Delinquencies and credit card debt are up sharply, suggesting not much headroom left. Debt is extremely expensive. There is no capacity for mortgage refinancings

If wages outgrow inflation, then corporate margins compress, which still likely means layoffs

Once consumption slows, pressure on already strained corporates grows not gradually, but exponentially. Labor hoarding becomes tough to defend

Government stimulus (IRA & infrastructure act) amount to ~0.5% additional GDP growth p.a., unlikely to be sufficient to change above dynamics. Further, the deficit has to be financed, with QT and lack of credit growth, that role falls to private deposits

China’s reopen is happening, but its government likely prioritises domestic goods and services

Interest income is offset by rising consumer debt that is much more expensive (see credit card rates above). Further, savings are skewed to top quintile and many bank accounts still do not pay interest

Awareness of this Wile E. Coyote moment is limited, in my view, especially at the Fed. However, yes, this could still change in time

Conclusion: Putting the pieces together, the US economy awaits a formidable storm in the combination of weakening consumer spend and a very fragile business sector, in particular within manufacturing industries. Few dynamics come to mind that can change the course of action in time, however they should not be ruled out

Finally, these key questions arise:

Timing: When does this moment occur. From an investors’ perspective, early is also wrong. Is this a Q2 event, a H2 ‘23 event or a '24 event?

My sense is that we see it happen over the coming quarters, with capital markets soon frontrunning it

Response: How will the Fed react? Does cutting rates bring back inflation? Is cutting rates sufficient to put new money in consumers’ pockets?

It seems likely that the Fed reacts late. However, at the end of the day, US institutions are savvy and pragmatic, and a forceful response likely follows

Exit: What is the exit strategy, what gets the economy out of the potential hole? Stimulus cheques to consumers? Government infrastructure programs like Roosevelt’s New Deal?

I have no good answer at this stage, but am sure the right steps will crystallise at the time

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

Should the above analysis be correct (keep in mind - maybe it isn’t), then a material risk off moment awaits later in the year, where all assets go down except US government bonds and likely the US Dollar. We are not there yet, and likely see at least another bear market rally before, but the moment is getting closer (Q2?)

I had mentioned how in a “risk-off” context the economy, from corporates to consumers, is starved for cash. Historically, all assets were sold to raise that cash

As such, in my view, which may be wrong, US Dollar cash pays 5% interest and is a great place to park one’s money. It also explains why I believe ‘23 to be a year where US government bonds, for some extended time at least, can do well

Further, I had written in various posts that I am patiently waiting for a sell off in long-term US government bonds, to establish a position with the margin of safety that is created when everyone is on the other side of the boat

I believe this is now the case, see below yesterday’s tweet where I show a commentator representative for consensus who expects that the “only” way for US yields is higher, also see similar calls from Jim Cramer or Treasuries making it onto media headlines - all contrarian indicators that tell me it is time to buy bonds. Yesterday, I have put the majority of my capital put to work in 20-30 year treasuries (TLT), sticking with Stan Druckenmiller’s view of concentrating high conviction positions

Should I be wrong with the economic view and inflation remains higher for longer, bonds likely trade down. However as long as the Fed is deeply committed to fighting inflation, these should remain mark-to-market losses, as further hikes make a subsequent recession more likely. The position likely only persistently loses if Fed throws in towel against inflation and/or stimulates too early

Moving on to Equities - as the tweet above states I covered shorts yesterday morning as I believe that lower yields still create a bid for equities

However, I do expect this relationship to flip later this year, in fact possibly soon, for stocks and yields to then trade in the same direction, in my expected case down when “risk off” materialises. The catalyst could be either worsening coincident economic data, or lower earnings guidance as corporates give up on 2H ‘23 recoveries - this moment could be in Q2, possibly even towards the end of this month

Please keep in mind, in my view, the bear market is likely not over, and for the conservative investor, life is easy at the moment as one-year and two-year US government debt pays 5% interest

does wile e coyote necessarily mean inflation comes down?

Sweden for example has much weaker growth than US, yet with higher inflation (and increasing YOY).

YEP, SOUNDS ABOUT RIGHT. But it is a shifting situation and surprises from rest of world, esp Spring Russian offensive and more geopolitical lines being drawn, it will be fluid. Anyway, way too much debt globally and expect that to be a factor. No satisfactory solution here but some of it must be destroyed. More inflation as reshoring and near-shoring manufacturing and industrial production will be expensive for all.