Voodoo Economics

Why the UK's travails are a stern warning to Europe and the US

Regular readers will be familiar with the paradoxical tension I see between a highly indebted Western world and the necessity to raise interest rates to combat inflation. I spelled this out in previous posts including “The Plight of the UK”, “The Emerging States of America” and more recently “Quantitative Frightening” were I predicted the current FX and Bond market crisis. Over the past week, this tension received rocket fuel in the UK’s case, following the introduction of tax cuts by the new government

While markets may have overshot in the short term, this posts explains why their panic is warranted in the medium term, and why this episode is likely a preview of what awaits Western economies in 2023, when the slowdown will fully arrive

As always, the post closes with a current outlook on markets, where I discuss why despite my overall negative view I covered shorts and bought software exposure in last week’s market rout. For real-time updates on this and many other topics, follow me on Twitter

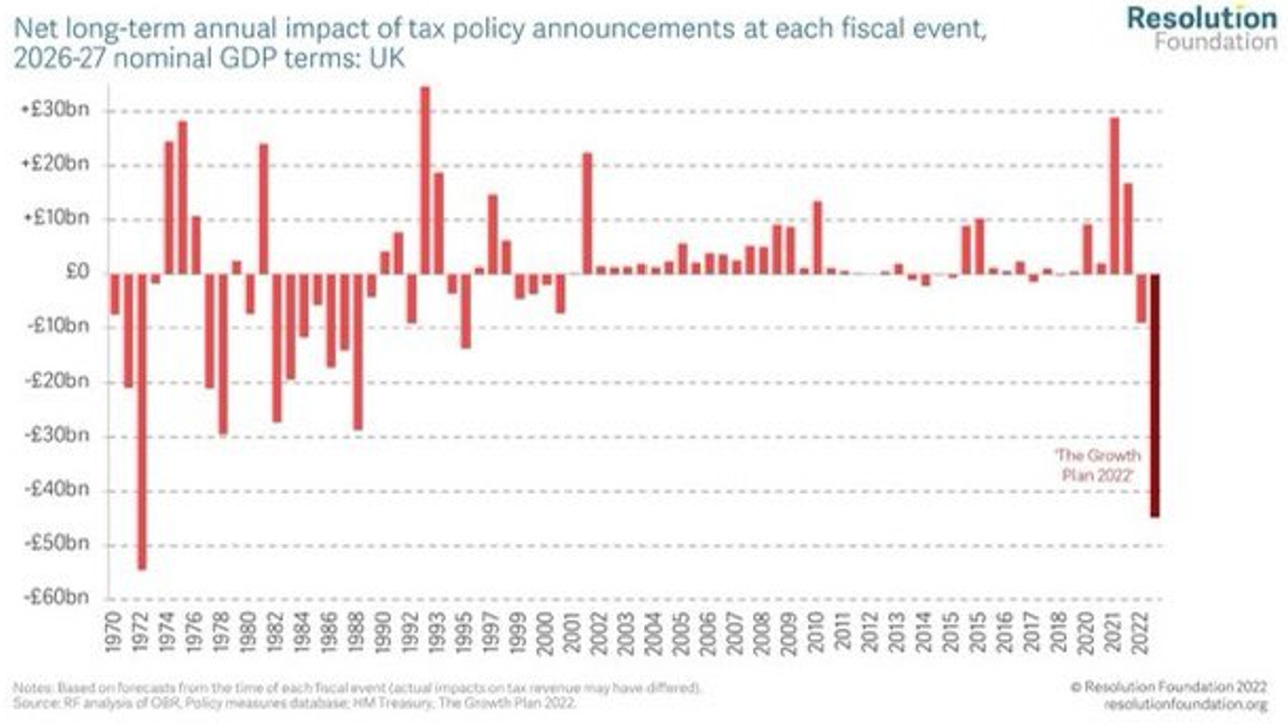

This past Friday, the UK’s newly inaugurated chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng unveiled “The Growth Plan 2022” - an aggregate £55bn of tax cuts, the largest since Anthony Barber’s 1972 budget

Particularly notable was the emphasis on tax cuts for high earners, with the bulk of the £55bn composed of a top-bracket income tax rate reduction from 45% to 40%

What is going on here? Prime Minister Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng follow the philosophy of “trickle-down economics”, whose biggest champion was Ronald Reagan in the early 1980s. How is that exactly meant to work?

The sequence goes as follows: Cut taxes for the rich, they will spend more, that spending stimulates the economy. That way, jobs are created and everyone benefits

Here is the massive issue with it:

Trickle-down economics is very expensive. As taxes are cut, government revenues are reduced. Now, the cuts may indeed stimulate growth, but historically this has not compensated for lower revenues

The balancing valve is higher debt. During “Reagonomics”, from 1980 to 1990 US public debt to GDP increased from 27% to 50%

The alternative to higher debt would be to cut government spending

For the UK, this is frankly not a viable option. Any of my readers living here will know how stretched most public services are, from an NHS unresponsive to emergency calls to businesses giving up on an understaffed police for crime prevention

Needless to say, if the government were forced to cut back on public services to fund these tax cuts, it would face stiff public resistance

More generally, tax cuts currently do not rank highly even on the affluents’ agenda of political desires, amidst high inflation and a world in turmoil. Truss and Kwarteng are “fixing a problem” that no one complains about

This is very different to Reagonomics. Income taxes were sky-high coming into the 1980s, with 70% for the top income bracket. It is fair to say that they stifled business and were a real issue

Equally, in 1980, after 15 years of high inflation, government debt levels were low, with plenty of room to expand. Today, this is completely different

Today, the biggest issue on the publics’ mind is inflation, not growth. Debt-funded tax cuts fuel inflation, as they are funded with debt, i.e. newly created money that increases the money supply

With all that in mind, what did financial markets make of this? Short answer - they hated it:

The British Pound collapsed by 10% in a week, a move typically seen in Emerging Markets currencies

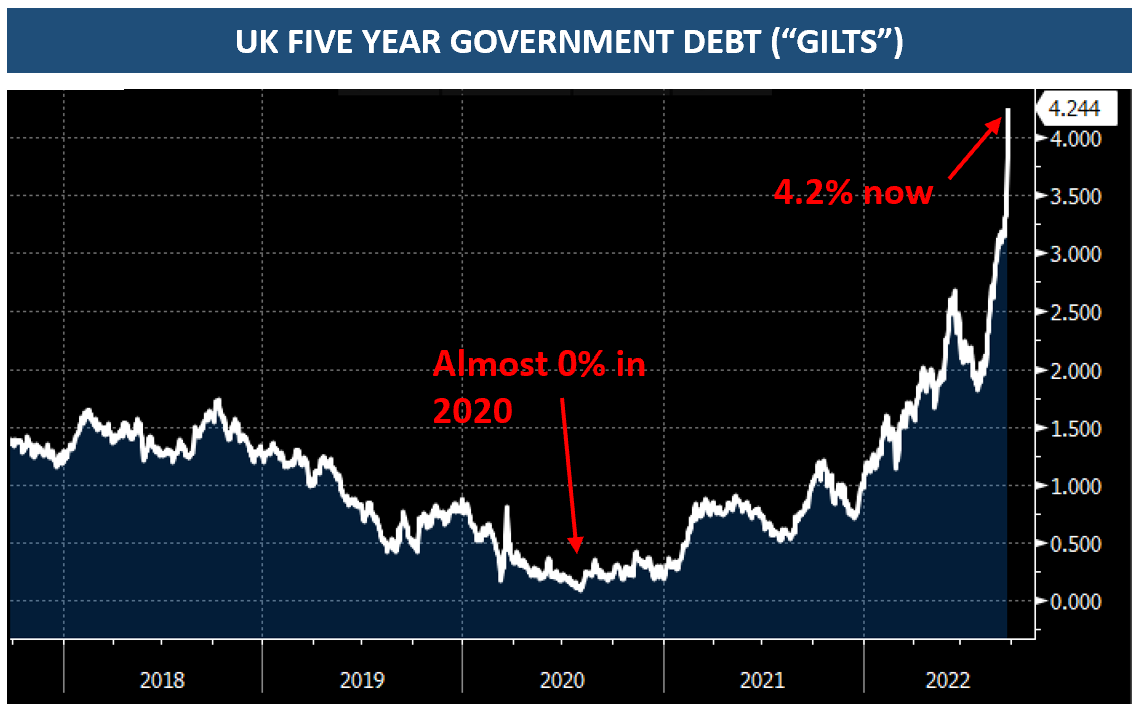

This was mirrored in the market for UK government bonds (“Gilts”). The five-year Gilt violently blew out to 4.2%, the largest 5 day move in 43 years

So why did markets hate it so much? The short answer - because the UK is seen as overindebted

It simply cannot afford another £55bn debt on top, in addition to the recently committed £120bn to keep household energy prices at £2500 p.a. (together ~8% GDP). In fact, it would need to reduce debt

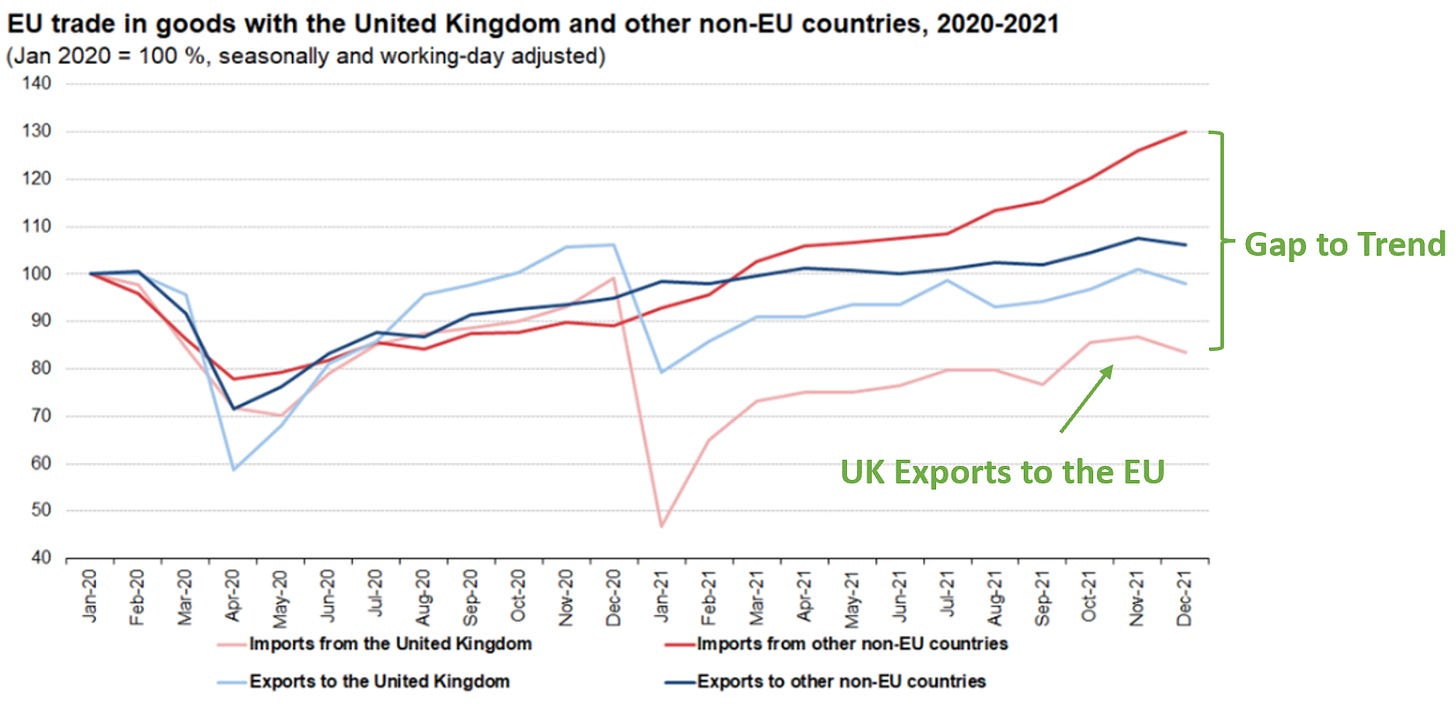

Further, Britain is an import nation and its export weakness was exacerbated by Brexit (see chart below). Its current account deficit increased to 9% of GDP, or ~£190bn. This is money that foreigners need to come up with. To do so, they need to believe in the UK

Liz Truss’ and Kwasi Kwarteng’s voodoo economics ignore the most basic, common sense budget tenant of not spending more that you can afford. Thus, financial markets lost faith in the UK

The doubt is highly warranted. Between 2000 and 2021, the UK ran by far the highest budget deficit of any European country, in spite of George Osborne’s cuts to many public services following the financial crisis

Summary: The market drives up UK interest rates and sells the British Pound, because it has no interest to to buy the debt of a fiscally irresponsible, overindebted nation

And because of inflation, the buyer of last resort (i.e. the Bank of England) is not in a position to fill this gap. In fact, the BoE just started selling its bond holdings (“Quantitative Tightening”)

Now, these higher UK bond yields not only drive up the cost of government debt. They also seriously hurt elsewhere - in UK consumers’ pockets

The UK consumer already has to endure record inflation, with energy prices twice as high than a year ago despite the £2500 p.a. cap

Further pain is caused by the lower Pound, which drives up prices for essential import products, in particular food

Add to this now the pain from higher interest rates. How? Most UK households are homeowners and these homes are bought with mortgages. The interest on these mortgages typically is only fixed for the first 2-5 years, afterwards it adjusts to higher benchmark rates

Thus, with some delay, the increase in Gilt yields translates to an interest rate shock in mortgages. The below chart shows UK mortgages rates adjusted for affordability over time. The most recent move is unparalleled

UK average household income is ~£31k p.a. The average UK mortgage is ~£150k, with ~£600 monthly payments (half interest/half amortisation) that rise to ~£1000+ as rates go from 2.5% to 6% = a >£4000 hit!

If anything, the late 1980s come close. The stiff mortgage rate increase at the time was then followed by a 20% decline in nationwide house prices (32% in London) from 1989-19931

The UK Consumer will be squeezed from all sides. Without help, consumer credit defaults are likely

Roughly 1.4 million UK households are set to refinance their mortgages over the coming year. This is a substantial chunk of the roughly 12 million owner-occupied and 2 million buy-to-let mortgages that are currently in place. How will they afford higher rates?

Some lapses in regulatory oversight add to these dynamics:

Banks’ lending standards evolved around keeping mortgage payments flat. After decades of low interest rates, it seemed implausible to regulators that interest rates would ever go up again2

So while interest expense indeed remained roughly the same over time as a share of income…

… the loan-to-income ratio went up, a lot, as house prices increased

If house prices decline similarly to 1989-1994 (see above), many mortgages will be under water, making it hard to refinance them

Of course, UK consumers could tighten their belts and pay up. But more likely, they will be really angry as they get squeezed once more

The UK is a very unequal society for European standards (see chart below). Being poor is really tough here, so accepting further belt-tightening after a miserable decade is unlikely

Conclusion: The UK’s situation is already very shaky, and the tax cut plans are unsustainable. So what is the endgame? The following options come to mind:

A Policy U-turn - There is historic precedent, financial markets forced a u-turn from Anthony Barber in 1972, Francois Mitterrand in 1983, or Ronald Reagan’s first tax cuts in 1981 when inflation was still an issue

The Bank of England resumes QE - This would both provide a buyer for the additional government debt as well as calm Gilt markets. If done while other central banks are still tightening, the Pound would likely be hit hard, and inflation would accelerate further

Increase the domestic savings rate - this would require UK consumers and corporates to stop consuming and investing in a pretty dramatic way in order to finance the government. I find this unlikely

Spending cuts - given the poor state of many public services and the intense focus on them, I again find this unlikely

The US Fed resumes QE - this would provide the world once again with additional balance sheet capacity and remove all current stresses in financial markets, including the UK. It would likely come at the expense of higher inflation, thus unlikely to be imminent. I also notice the Atlanta Fed’s Raphael Bostic calling Liz Truss’ program “unhelpful”, suggesting the Fed is not keen to sort out the UK

Inflation collapses - inflation could decline much faster than anticipated. This would bring down yields and once again allow for more leverage. I do not find this very likely given how hard it historically was to tame inflation

It seems likely that we see a combination of some of above. The Pound likely falls further after a rebound from current oversold levels. The tax cuts might not make it through Parliament as Tory backbenchers refuse the vote. The BoE likely ends its QT program early

Either way, given the intense pressure on the UK consumer, a deep recession is likely, and in line with the 1990 example, a decline in house prices seems plausible

The UK’s rough experience with financial markets this past week is a preview of what’s to come for most developed nations. Debt levels are too high everywhere, but conducting QE to accommodate them likely incurs further inflation. Thus, the US Fed, which is the backstop for the entire Western financial system, faces a choice between the following:

Cause a financial crisis, first abroad, then domestically as it yanks yields high enough to successfully combat inflation

Avoid the financial crisis by restarting QE (or a variation thereof, such as changes to the RRP, bank regulation or Treasury buybacks) and accept higher inflation

Conclusion: My best guess is it will be both. First more pain for financial markets, then the Fed relents and accepts higher inflation. I expect said “pivot” not to occur before Q2 2023, but as things in finance often happen first gradually, then suddenly, this may also be earlier

At the heart of this dynamic is the collective, mistaken assumption that inflation would never return. In the words of Janet Yellen, as recently as March 2021

What does that mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

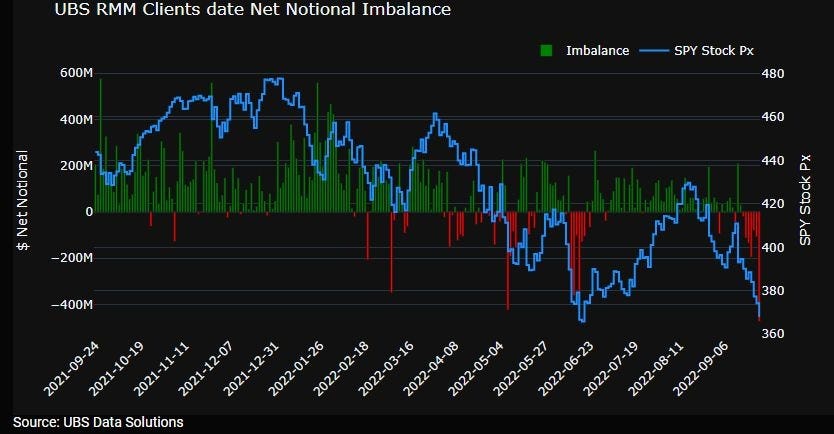

Equities - At the end of the day, investing is an exchange of views where only one party can be right. This is why the odds are tilted in one’s favor when the “other side” is emotional, or even panicky. Last Friday was such a day, with the highest Retail selling volume YTD

For this reason, despite my overall continued negative assessment, I covered all shorts late last week and went long (see Tweets here and here), with the US Software index (IGV) as vehicle of choice

Software valuations have come down (see chart below), these businesses are inflation winners with high pricing power and high margins. They are often sticky and late cyclical. There are many indications that Q3 earnings will be very good, the sector is down 44% YTD and very hated. Most importantly, interest rates may have peaked (see more below), which would reduce valuation pressure

I used a stop-loss at -5% which gives me an asymmetric risk reward, should this be a turning point, as these shares can easily run 15-20% to be still down significantly YTD. With a 4:1 risk reward, I need trades like these to work out 25% of the time to break-even, which gives me plenty of cover should I be early or wrong here. Finally, the trade feels deeply uncomfortable as everything screams the other way - a typical feature of turning points

On markets more broadly, while volatility is high and headlines are grim, nothing has actually broken yet. We haven’t seen a big default event, so there is still plenty of space for alternative narratives

The next narrative I could see is a return of US domestic recession fears, the Fed would have overdone it and we’d risk going into deflation, a pivot is near etc. This could drive risk assets, and I would point to the recent outperformance of Bitcoin as evidence for this narrative

A narrative is just that - a story that explains price action. It stays alive until proven otherwise, as long as enough market participants believe it it. The true reason for a potential rally may simply be that everyone who wanted to sell has sold

Medium term, my views remain the same as before. I do not think the bear market is over

Further, on various:

European Banks - I changed my mind here and turned more constructive. It seems likely that high capital ratios will prevent a significant spill-over of defaults onto banks’ equity positions. Meanwhile, every percent higher in interest rates represents ~20% more bank revenues. Banks will trade with beta to the market, but could be a big winner of a higher inflation environment, in particular in Europe after a decade of negative interest rates. These may do very well in an eventual cyclical recovery

US Treasury Bonds - With the 10-Year in reach of 4%, these seem very oversold now and a pause is warranted. However, unclear how long it might last, as inflation pressures are still substantial, and there is also QT as well as the FX issues for foreign UST buyers, so new highs seem eventually likely. Either way, the Fed yo-yo between fear of breaking things and fear of inflation seems likely to continue. For now, we seem to have arrived at the fear of breaking things again, with the Chicago Fed’s Charles Evans on tape this morning stating “he is nervous rate hikes might go too fast, too far”. A pause in the rise of the 10-year UST would be supportive for risk assets

Cash - I can only repeat my view that 1-year T-Bills with a 4% yield are very attractive. I find it unlikely that last week was THE low in the current bear market, given the current central bank tightening will strain global economies well into late 2023 while inflation remains high. Thus, T-Bills remain a good and relaxed alternative to risk assets

I hope you enjoyed today’s Next Economy post. If you do, please share it, it would make my day!

Of note, the rise in UK rates in the late 1980s was also driven by higher US rates in response to US domestic inflation, similar to today

While it seems hard to believe that the BOE loosened mortgage standards as recently as July, this will likely have little impact as the crisis is already here and banks will now be very careful with lending

Fantastic analysis. Consider charging for it 😊

Great piece Florian, thanks for sharing!