Regular readers will have noted that I’ve turned negative on commodities earlier this month (see here and here), a sector currently very popular with investors. While the future is uncertain and many variables including China lockdowns are at play, the biggest reason for this pivot was the assumption that we’ve passed the US cycle-high and the path towards a recession has moved from theoretical, as outlined early in the year, to tangible

This call is not based on gut-feel or a misplaced indulgence in doomsday views (keep in mind - every recession is followed by a boom!). It’s a reflection of economic relationships that have proven durable in the past, and are likely to prove durable again now

This post lays out the case in detail

To start, one might wonder - why does economy activity involve any cyclicality at all?

Indeed, most of our daily expenses are recurring and fairly constant in size. Just think of lunch and dinner costs, gasoline or subway tickets, media consumption, rent or phone bills

However, some expenses are both much larger, and occur in much more irregular intervals. These include residential fixed investment (i.e. buying or building a house) and consumer durables (e.g. cars, home appliances, mobile phones etc.)

In an upcycle, consumers feel confident and cash-rich. So they are willing to shell out for these goods

This creates a positive flywheel. Businesses hire staff and increase production to accommodate demand, which in turn adds to purchasing power

Eventually demand subsides as the market becomes saturated. This coincides with said increased production capacities. An inventory build ensues

Producers cut both prices and production to clear the inventory into a now satiated market. This slows economic activity, a downcycle begins

Within this cycle, housing plays a pre-eminent role. Why?

Homes, in particular the primary residence, are a highly emotional product. Consumers assign much personal and nostalgic value to it. For this reason, they’re very reluctant to sell at a lower nominal price than where they bought. And unless there is a leverage or employment issue, they also don’t have to sell

So when housing demand wanes, home owners don’t respond with price cuts. If they don’t receive at least what they paid, they’re inclined to wait

As a result, when the cycle turns, housing volume collapses

Let’s take the L.A. housing market in the early 1990s as an example:

During the late 1980s home prices rose fast and housing affordability suffered. The market was out of balance. Home owners didn’t want to take a nominal hit, so the prices went sideways for 7 years, while volume declined 52%

This is in contrast to many other products, which are typically cleared off the market by discounts, which means volume declines are few and brief

In housing, volume can literally fall off a cliff. Because the sector is so large, this creates ripple effects across the economy. Just think about all the products needed for a newbuilt home: Paint, lumber, fridges, construction, garage doors, carpets etc. etc.

For this reason, housing is the most important lead indicator. Historically, eight out of the last ten recessions have been preceded by softness in housing

The following two charts are taken from the excellent paper “Housing is the Business Cycle” by UCLA Economics Professor Edward Leamer. It was published by the Kansas Fed in 2007, just before the subprime housing bust

The percentages in the table denote the contribution to GDP weakness in the year before a recession. “Residential Investment” is the biggest contributor, followed by Consumer Durables1

Let’s look at the behavior of all sectors in the table during an average recession. It becomes clear that it’s always the consumer who leads the cycle

The chart on the left shows the consumer segments, which all turn down ~4 quarters before the beginning of the recession

On the right you can see business segments, they only contract once the recession has started

Summary: The business cycle, which should be really be called consumer cycle, is lead by housing which kicks off the dominos, to be followed by consumer durables, services, and eventually business expenditure

The last domino to fall is employment; Layoffs typically occur towards the end of the cycle

Ok, that’s interesting, but why is this relevant now?

It’s relevant because the US housing market has likely reached a turning point

The Fed’s strong verbal intervention drove up long term bond rates, and with it the cost for the 30-year fixed mortgage, which is most commonly used when Americans buy a new home

There are several indications that this aggressive move is cooling the sector

Mortgage applications are down 50% y-o-y. Equifax, which provides credit scores needed in the application process, guided to a “significant further decline of the U.S. mortgage market”. Wells Fargo reported lay offs in its mortgage unit, as did several mortgage tech startups

The all-important metric of days-on-the-market before a house gets sold moved up last week, against its typical seasonal pattern

The National Association of Homebuilders (NAHB) sent a letter to the White House “Urging Action on Issues Threatening the Housing Industry”

As an industry lobby group, they are mainly concerned about their industry’s revenues

They also famously complained when Paul Volcker raised interest rates in the early 1980s to tame inflation, when they sent bricks of wood to the Fed’s office

A housing slowdown also makes much logical sense

The move in mortgages has brought affordability back to levels last seen pre-2008. While this may not be historically extreme, it comes at a time where everything has shot up in price. Demand destruction levels are likely lower than history across the board, as they all occur at the same time right now

It’s not only housing, there are many signs of weakness also in Consumer Durables

The Manheim used-car index weakened further over the first half of April. I had written about trucking weakness2 which has continued. Whirlpool (kitchen appliances) yesterday lowered its guidance and cited that it was not able anymore to pass on the entirety of its raw material cost increases

Summary: The downcycle is likely under way

The speed is unclear. However, there is some risk that this cycle evolves faster than the historical ~8 quarters (see chart above), as its upleg was artificially accelerated by stimulus programs

Ok, so we’re heading into a recession. What does that mean for the inflation debate?

Most obviously, lower durable goods demand removes pressure from commodities. Goods are ~20% of the CPI and highly volatile, this will make a noticeable difference (if the effect is not negated by reduced Chinese production capacity)

However, the price-wage spiral is still in full swing, and the ratio of vacancies to unemployed remains historically tight. Employment is only the last domino to fall in a downcycle, so this tightness will be a significant source for inflationary pressure for the foreseeable future

After recent Fed action, 10-Year real rates have moved to slightly below zero. This is still not enough to incentivise financial behavior to act in a disinflationary way. Real rates would likely need to be meaningfully positive for that

Inflation needs structural relief. A reprieve caused by a recession would only be temporary

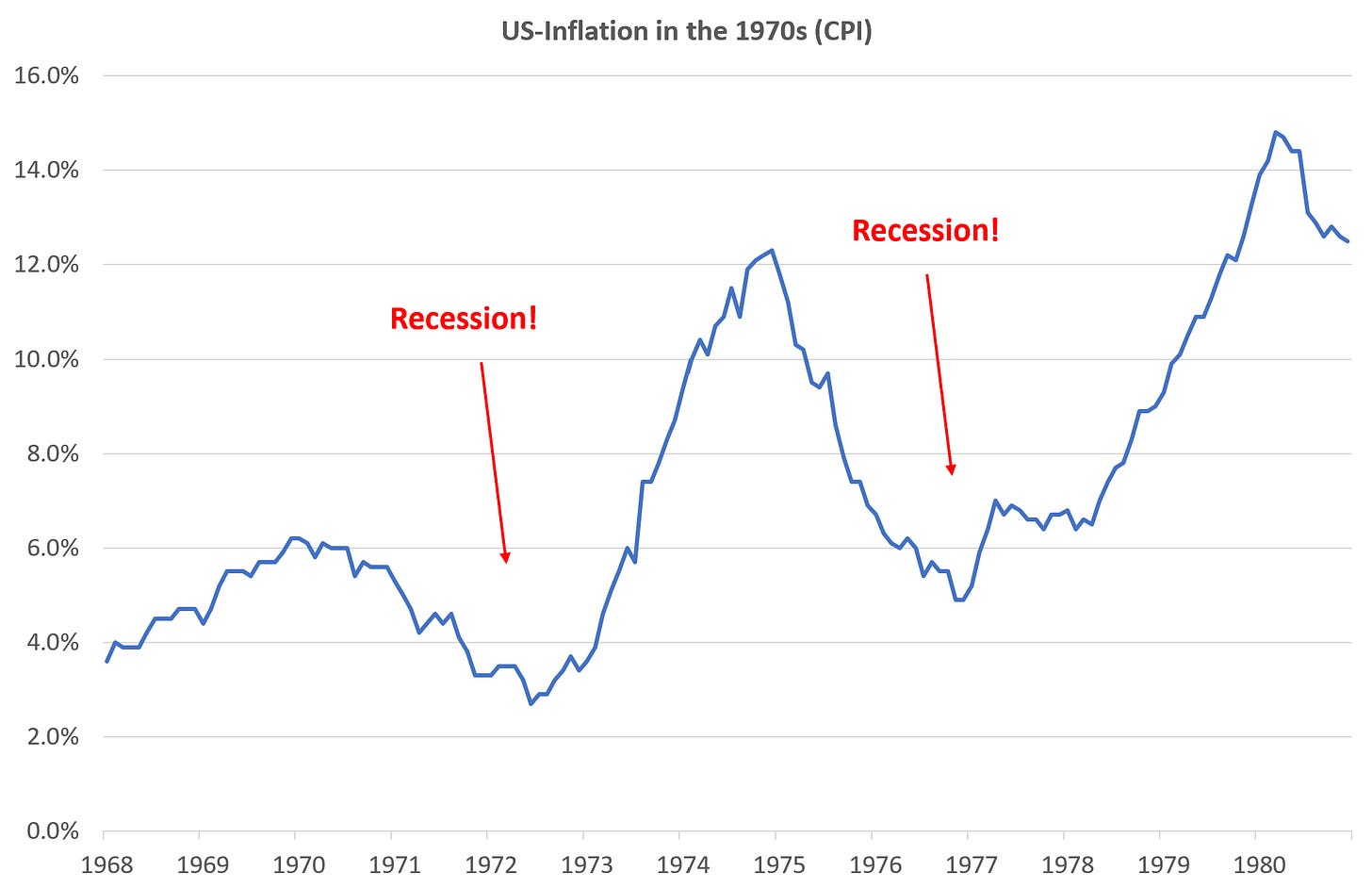

The chart below displays the sequence of inflation in the 1970s. Two recessions provided temporary reprieve. However, as the Fed wasn’t serious about fighting it at the time, inflation came back worse each time

So the big question is, will the Fed reverse course when the recession hits, likely towards the end of the year, and undo any gains in the fight against inflation? It’s too early to tell, but two things are noticeable:

Jerome Powell does not miss an occasion to reference Paul Volcker, who was very determined in his fight against inflation in the early 1980s

This may all just be just politically motivated talk, but we may see a rare occasion where the majority of the US public indeed welcomes a slowdown. Over the past 18 months, ~20 million have come out of unemployment. But because of inflation, living standards have deteriorated for ~180 million Americans, including ~50m pensioners whose payments aren’t linked to inflation

What does this mean for markets?

First, some general observations that flow from this post:

The US stock market is expensive in comparison to bonds. A downcycle means that earnings estimates will be reduced, which hasn’t happened yet. Together, this means pressure on both the “P” and the “E” of the P/E-Multiple, so expect more downside. Unless you want to short, cash is king

Tech and High-Growth would be a natural choice at this stage of the cycle. However, the past upcycle has coincided with a tech bubble which, similar to 2000, created unsustainable revenues and earnings that originate from bubble money circulating between these businesses. This needs to wash out before the sector is again attractive

US government bonds are getting more interesting, e.g. 5-year rates at ~3%. However, several arguments speak against long bonds at this point in my view. (1) government deficit spending has again become a relevant variable for bonds, and it’s unclear what path the US government will embark on, (2) term premia are still historically low3 and (3) real rates are likely still not high enough to lastingly tame inflation

I had mentioned above the strong emotional bond to one’s owned primary residence. This bond is clearly much weaker for second homes or real estate that had been acquired to park money. Expect significant weakness in those markets

Commodities have likely seen their cycle-high. Yes, the long-term story remains strong, which means that cyclical troughs are likely higher due to much discussed underinvestment. But commodities are called commodities for a reason, and permabulls risk the same fate as Cathie Wood’s ARK if they only look at the supply side. Take this quote from the recent Alcoa (aluminum) earnings call:

The topic of commodities inevitably leads to China, given the country’s outsized market share in most of them. It’s fair to say that China faces a huge crisis. Its leadership is hellbent on zero-Covid policies, but Omicron BA.2 is so infectious that zero-Covid seems a mathematical impossibility. I won’t pretend to know how this plays out, just one thing of note:

China’s biggest GDP contributors are exports to the West and domestic real estate investment. The latter is suffering from overbuilt, and export demand likely weakens with the US downcycle as laid out in this post. If lockdowns are lifted, commodity counterrallies can ensue, but the overarching trend is now likely down

There are two historical exemptions: 1953, where the recession was preceded by a dramatic reduction in government defence expenditure following the end of the Korea War, and 2001 when businesses cut back on inflated expenditure on tech equipment

Trucking in itself is a lead indicator, and sector weakness has predated all US recessions. However, its hyper cyclical nature means ~50% of trucking demand declines have occurred without being followed by a broad recession. For more details see this 2019 Convoy study

The term premium is the difference in yield between long-term and short-term bonds, and a reflection of higher inflation risk and bond supply over the longer time frame (see this speech by Ben Bernanke). The Fed estimates that the term premium on 10-year Treasury bonds has historically averaged 1.56% since 1961. It basically disappeared between 2014 and 2021 and is currently at 0.61%

Thanks Florian! This was very insightful!

Thank you Florian for taking the time to write this up! Insightful as always!