From Inflationary Boom to Deflationary Bust

Why the Silicon Valley Bank Crisis is a seminal event into a new economic era

In last week’s post I described how several adverse dynamics now align for the US economy to create a cliff-like moment where economic activity markedly drops. These include depleting consumer excess savings, in particular for the “lower 80%”, a slowdown in previously elevated goods demand and likely higher unemployment from overstaffed cyclical sectors. This all coincides with monetary policy that is historically tight for the current stage of the economic cycle. Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) is the first major casualty of this policy stance. Its demise likely accelerates the economic downturn

The acceleration is less due to SVB’s case itself, which has been solved with the government bailout. It is because this episode alerted millions of Americans to the fact that (1) their deposits pay nothing and (2) are possibly unsafe. This realisation increases deposit costs especially for US regional banks, and in turn lowers their willingness to lend. The result is a classic credit crunch which likely amplifies the deflationary trends already underway

Thus, after a wild inflationary boom, the US is now likely headed for a deflationary bust. Money supply will contract sharply in the coming months while the economy slows and unemployment likely increases, with deflationary CPI prints likely by H2. I’ve sketched this out in many previous posts (see here, here or here). With every month, the contours become more pronounced

This outlook is also the key reason for my decision to invest in US Treasuries, where the patient wait to enter paid off with top-ticking the recent high in yields, to be followed by a historic bond rally

Today’s post explains what I see as pertinent dynamics from the SVB crisis into the deflationary bust, and as always closes with an outlook on current markets

Let’s start with how we got here, to the second largest bank failure in modern history after Washington Mutual in 2008

Indeed, we have to go back to said Great Financial Crisis, when Quantitative Easing rose to prominence, the practise of Central Banks buying assets such as bonds or mortgages from asset owners in exchange for cash, thereby driving asset prices up (please see details in this previous post)

Initially an emergency measure, in 2010 Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke elevated QE to a permanent feature in the Central Bank tool box. To stimulate a sluggish economy at the time, he explicitly targeted QE’s “wealth effect”:

Needless to say, asset owners did not spend more, as they already had plenty of savings. Instead, QE priced lower-income groups out of asset ownership (e.g. homes) and generated much social discontent

Irrespectively, over the next ten years, QE went into overdrive, and during Covid alone $5tr were printed by Central Banks. Due to the Tech boom, much of this money ended up in Silicon Valley, with SVB as its bank

The SVB bankers were overwhelmed by the deposit flood coming through their doors. With insufficient demand for business loans, they put much of this cash into mortgages at rock-bottom, fixed rates

Then, interest rates and with it deposit costs started to rise. Further, SVB’s clients, amongst them 55% of America’s start-ups, burned more cash, both leading to a decline in deposits

Eventually, SVB had to do an emergency capital raise. In a prime example of reflexivity in financial markets, this alerted SVB’s customer base to the imbalances at hand, so they pulled their money, thereby making the situation much worse - $42bn or 25% of SVB’s deposits was withdrawn in one day

As these proceedings made headlines, other depositors at both SVB and similar US regional banks got nervous. They wanted to take their money out, too. Without intervention, a banking crisis was in the cards

That crisis was averted by the US government over the past weekend. It shut down SVB and Signature bank, a smaller but equally weak peer, guaranteed all deposits (not just the legal $250k minimum), and introduced a facility where banks can fund themselves at very favorable terms

Today’s post focusses on the repercussions of this episode, rather than a judgement of the de-facto bailout, so just a few words on the latter:

The government’s actions were right from a short-term economic view. Any deposit default would have lead to a panic amongst clients of most US regional banks. Bank runs would have ensued, leading to severe financial instability

Further, no one can expect SVB’s small business clients to understand bank counterparty risk, if even Wall Street analysts don’t understand it. Many hard working entrepreneurs trusted the soundness of America’s banking system and would have been the “sacrificial lamb”

However, it was wrong from a moral, and long-term economic view

Once again, a crisis was solved with a bailout and no one had to feel any pain. Once again, the increased sensitivity of risk to the collective economic mind was avoided, to be paid by future generations acting more carelessly and needing ever greater bailouts - thus, entrenching the much quoted “moral hazard” even further

More so, SVB was a poster child of moral hazard itself. A toxic loan book, complete absence of risk management, lax KYC rules, discounted loans in exchange for exclusive client business - in summary, a reflection of the bailout culture of the past decade, and all under the eye of a sleepy regulator. The defaults on their loan book, much of which funded VC acquisition leverage, will now be paid by the tax payer (!)

The true issue is that after 40 years of ever higher debt levels Western economies are so fragile that the unassisted failure of the US’ 16th largest bank would have been enough to bring everything down

Either way, the bailout happened and the situation is now solved, is it? Unfortunately, no

Why are things not solved despite the bailout? Two reasons:

First, over the past week, millions of Americans were made acutely aware that their deposits might be unsafe

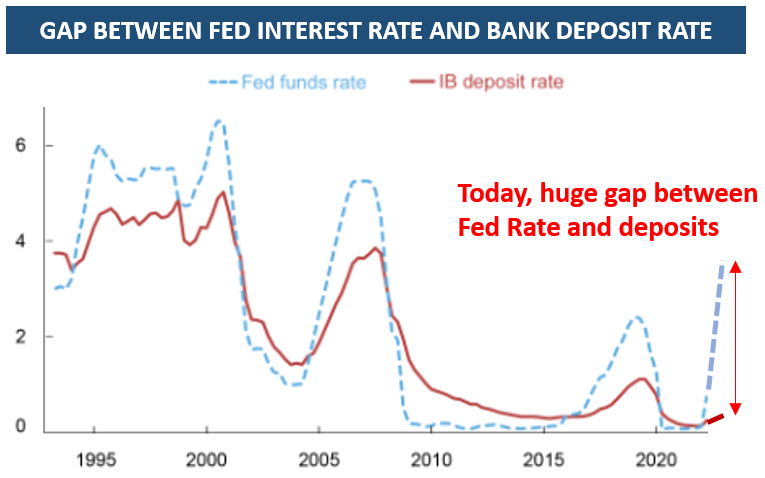

Second, they were also made aware that these deposits don’t pay anything, in contrast to alternatives which pay 4-5% (e.g. money market funds)

Consequently, many are now looking to move their money, especially if they are with one of the “unsafe” US regional banks. What has been seen, cannot be unseen. The emperor has no clothes

This caused the intense bid for US Treasuries after the weekend, we’ll see retail money market fund flows with some delay

Money centers such as JP Morgan or Citigroup have been “inundated” with money pulled from regional banks. Large banks benefit from tighter regulation and an overflow of reserves (another QE legacy)

But why is this deposit flight from US regional banks bad for the economy? It’s simple: In aggregate, these banks are a critical credit provider to the US economy

37% of all bank lending, 28% of corporate, 53% of residential and 67% of commercial real estate lending is done by US regional banks

Due to the SVB crisis, they now need to (1) pay more for deposits and (2) assume that their deposit base is less sticky than thought. What does that mean?

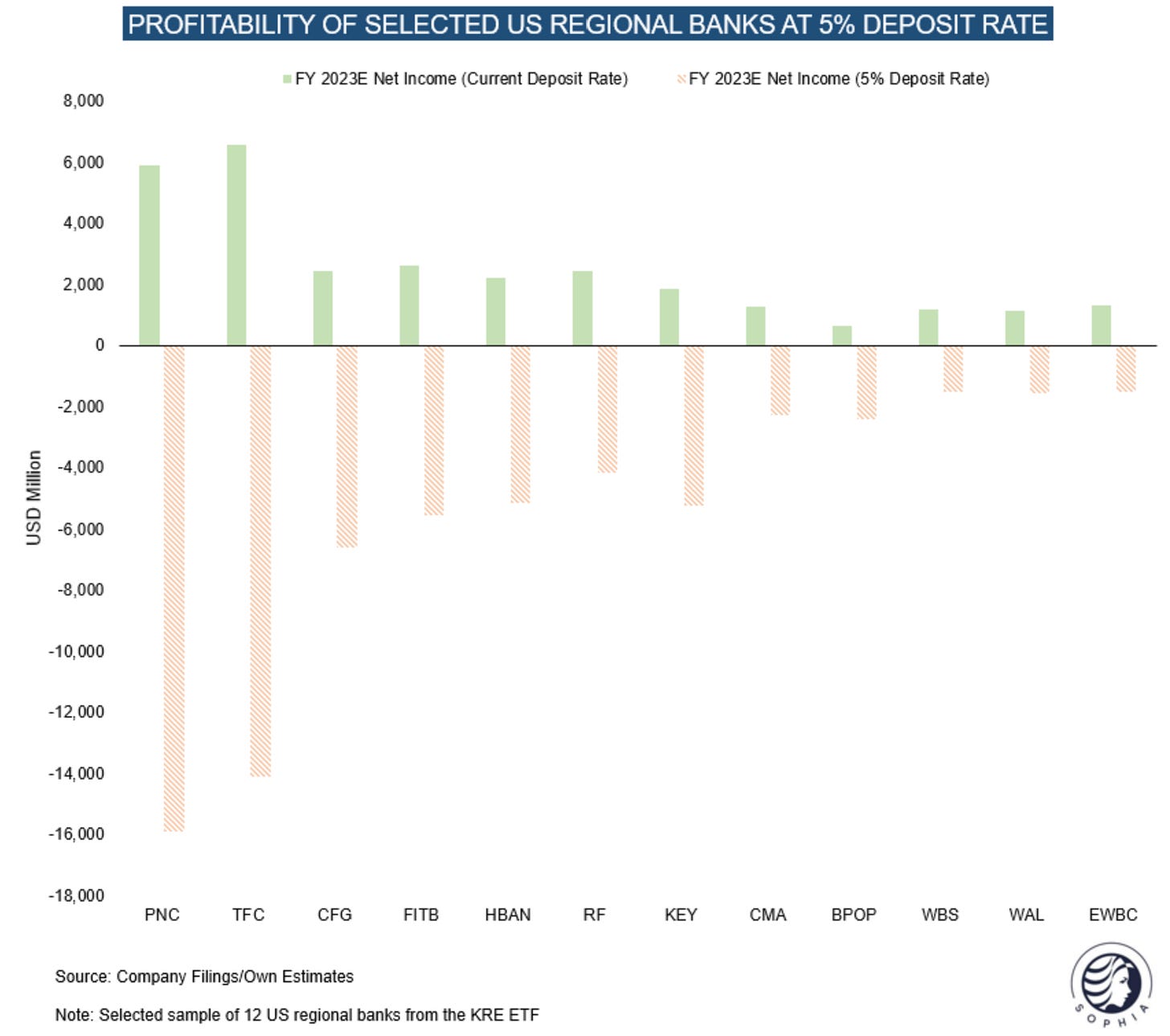

Particularly the higher deposit cost is a challenge. After a decade of low rates, the regional bank asset side is stuffed with low yielding exposure, even if parts are floating or hedged

As the chart below shows, if these banks were to pay market rates for deposits to prevent the flight, they would be deeply loss making. (NB: This would still be the case for many even at e.g. a 2% spread to FFR)

In addition, should a hard landing materialise, loan losses are likely significant, to weigh further on profitability. Just think of the commercial real estate exposure mentioned before

What does a stressed, unprofitable bank do? It reduces risk. How does a bank do that? By tightening lending standards and cutting back on new credit

I’ve shown the below chart before. Even before SVB lending standards were near historically tight, imagine where they’ll go in the coming weeks

Importantly, the deposit issue is made worse by QT, which overproportionally destroys small bank deposits and which I previously discussed here

Now, the big question is, how did we even end up in this bizarre situation, where banks could get away with paying nothing on deposits, while the Fed Funds rate is at 5%?

As I laid out in “Incentives and Inequality”, the reason can again be found in QE. As Central Banks flooded asset owners with cash in exchange for bonds and mortgages, this created trillions of new deposits (and reserves at large banks - please see same post for technical details)

Thus, deposits were not a scarce resource and banks felt no need to compete for them. And when rates increased dramatically last year, they could rely on the unawareness of many retail investors to higher yielding alternatives

Summary: The SVB crisis laid bare a fragile equilibrium caused by QE that only existed due to people’s unawareness. The veil has been pierced, and now deposit costs are going up while at the same time their stickiness goes down. As a consequence, credit available to the US economy will be constrained further, from already very tight levels - a classic credit crunch

Now, why is that deflationary, and why does it amplify already existing deflationary trends?

Inflation is, amongst other things, driven by the amount of money available. This is why the Fed is committed to slowing the growth of money. It achieves this by increasing interest rates, which slows credit creation, and by conducting QT, which indirectly transfers money from the private sector to the government

The Fed’s medicine is working, if we look at the evolution of deposits, or simplified, the money people have available to spend

While last year $1.2tr net new loans were created, Fed policies offset this growth in new money entirely, so it did not fan inflation further. NB: ‘22 loan growth was driven by lower rates earlier in the year, and revolvers drawn by corporates who lost access to high yield markets

However, since the beginning of ‘23, deposit decline went into overdrive. Why? Loan growth is now negative and QT continues at the same pace

Keep in mind, this data is before SVB happened (!), what will it look like over the next few months? Four dynamics drive the credit crunch from here

First - Two banks have been shut with a combined $300bn balance sheet. These financiers cannot be replaced from one day to the next, e.g. as former clients need to onboard somewhere else. SVB typically insisted to be the sole banker in exchange for favorable loan terms, Signature had a stronghold in NY commercial real estate

Second - US regional banks will curtail lending due to more costly and more unstable deposits, as laid out above

Third - Increased regulation as a belated answer to the crisis will curtail regional bank activity

Forth - Less lending will lead to higher loan losses, which damages banks further and leads to less lending → a self re-inforcing spiral

Now, looking at a broader monetary picture, M2 (of which deposits are part of) is currently shrinking year-over-year (!). This is important as M2 leads inflation by 1.5-3 years1

This historic anomaly only occurred before in 1931, 1921 and the late 1800s, all periods of crisis

In comparison, the often referenced 1970s saw entrenched inflation mainly as a consequence of several bursts of M2 Money Supply growth

Finally, we have to remember that this credit crunch coincides with an increasingly ailing consumer, as recent near-time retail data continues to confirm

Conclusion:

The SVB crisis will lead to tighter credit standards and lower credit growth than already the case. The dynamics resemble a credit crunch that is deflationary as it shrink the amount of “money” in the economy

At its origin lie decades of misguided monetary policy, with QE at its heart. The same monetary policies created the post-Covid consumer boom that is now abating, to coincide with said slowdown in credit creation

The US economy faces enormous headwinds that just intensified with SVB. It likely soon needs renewed provision of liquidity to fight of a deflationary bust

With the Fed looking to fight the inflation fires in the rear view mirror, this liquidity provision likely only comes when much more damage is done. And looking at past recessions, a tremendous amount of liquidity is likely needed to turn the ship around

At the same time, the economic structure has indeed changed, and whenever new liquidity is provided (which is still far off!), a resurgence of inflation is likely. I’d expect this to take place in 1H‘24 (?), with deflation until then

What does this mean for markets?

As always, below is my personal attempt at connecting-the-dots for my own investments. Please keep in mind - I may be totally wrong, nothing is more important than risk management, and none of this is investment advice

As today’s article explains, banks are the lifeblood of modern economies, and when they stop functioning, the remainder of the economy eventually follows

In a deflationary bust driven by contracting credit, the economy is in urgent need of liquidity. For that reason, everything will be sold, from stocks to houses to commodities to crypto to gold, in exchange for US Dollars and US Treasuries, the foundational layers of the world economy

This is why I am max long US Treasuries across the curve, as detailed last week. I also notice that hedge funds were once again on the wrong crowded side of this trade and thus fuelled the bond rally with record short covers

The deflationary bust is likely solved by a return to QE or some similar measure that provides liquidity to markets again (in Q4?). When that happens, all asset prices rise again, until inflation returns (1H’24?) and interest rates increases follow. For the avoidance of doubt - the moment of liquidity provision is not near!

Just as I’ve patiently waited to enter Treasuries at the right moment, I’m now equally patiently waiting for the right moment to to short equities again, as I expect a steep sell off in all risk assets once economic data confirms the “hard landing” I anticipate

Equity positioning is very bearish, which keeps me from applying shorts. As things are moving fast, this means I might miss the drawdown. Either way, long bonds and short equities has now become the same trade, something also discussed in last week’s post

I am however short levered loans via the SLRN and BKLN ETFs. These products have very limited upside and massive downside, should a hard landing materialise. I see levered loans as one of the epicenters of this crisis, see this post from December ‘22

There is a decent chance that the Fed pauses interest rate increases at next week’s FOMC. Financial conditions tightened to the equivalent of a hike, and it appears unwise to raise rates into a deflationary banking crisis. My sense is that emergency cuts will follow by the summer, and we will see much lower rates later this year. These will likely show limited traction as the economy does not want more debt. Thus I expect a return to QE or another, similar liquidity provision by the end of the year. Until then, the outlook for risk assets is - in my view, which may always be wrong - very difficult

DISCLAIMER:

The information contained in the material on this website article reflects only the views of its author (Florian Kronawitter) in a strictly personal capacity and do not reflect the views of White Square Capital LLP and/or Sophia Group LLP. This website article is only for information purposes, and it is not intended to be, nor should it be construed or used as, investment, tax or legal advice, any recommendation or opinion regarding the appropriateness or suitability of any investment or strategy, or an offer to sell, or a solicitation of an offer to buy, an interest in any security, including an interest in any private fund or account or any other private fund or account advised by White Square Capital LLP, Sophia Group LLP or any of its affiliates. Nothing on this website article should be taken as a recommendation or endorsement of a particular investment, adviser or other service or product or to any material submitted by third parties or linked to from this website. Nor should anything on this website article be taken as an invitation or inducement to engage in investment activities. In addition, we do not offer any advice regarding the nature, potential value or suitability of any particular investment, security or investment strategy and the information provided is not tailored to any individual requirements.

The content of this website article does not constitute investment advice and you should not rely on any material on this website article to make (or refrain from making) any decision or take (or refrain from taking) any action.

The investments and services mentioned on this article website may not be suitable for you. If advice is required you should contact your own Independent Financial Adviser.

The information in this article website is intended to inform and educate readers and the wider community. No representation is made that any of the views and opinions expressed by the author will be achieved, in whole or in part. This information is as of the date indicated, is not complete and is subject to change. Certain information has been provided by and/or is based on third party sources and, although believed to be reliable, has not been independently verified. The author is not responsible for errors or omissions from these sources. No representation is made with respect to the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of information and the author assumes no obligation to update or otherwise revise such information. At the time of writing, the author, or a family member of the author, may hold a significant long or short financial interest in any of securities, issuers and/or sectors discussed. This should not be taken as a recommendation by the author to invest (or refrain from investing) in any securities, issuers and/or sectors, and the author may trade in and out of this position without notice.

The M2-inflation relationship is clearest in extremis and when controlling for regulatory changes (e.g. changed banking regulation in early 1990s) and credit growth (e.g. credit shrunk post GFC and with it money velocity, offsetting M2 growth)

Great write up Florian! One small nitpick, you state the "bailout" will be paid for by the "tax payer". It was my understanding that the FDIC is picking up the whole tab by increasing the fees all banks pay to be covered by FDIC insurance (so all banks are actually picking up the tab). Am I wrong on that? Many thanks, Rick

From an international perspective it's not obvious how a US banking and liquidity crisis leads to demand for dollars and a stronger dollar. Near-term the dollar seems to be weakening. Could gold and crypto be better safe havens than US bonds?