Capital vs Labor (Pt. 3)

More signs that a corporate margin crush is underway, and a silver lining for employees

As regular readers may have noted, a recurring theme of my writing has been the ever-shifting balance of power between capital and labor in today’s global economy. While the 1950s, 60s and 70s featured a dominance of labor over capital, with strong real wage gains and continuously increasing trade unionisation, the pendulum swung the other way in the early 1980s, as the electorate was increasingly frustrated with the economic cost of excessive labor influence and favored policies to reduce it, while China’s addition to the global labor pool introduced fierce low-cost competition. It all went into overdrive after the Great Financial Crisis, when Ben Bernanke’s Fed tried to improve economic growth via the “Wealth Effect”. Central Banks would acquire vast amounts of government bonds to drive down interest rates (“Quantitative Easing"/QE”), thus driving up asset prices so asset owners would spend more as they’d feel richer (yes, that was indeed the idea…)

Aside of creating enormous inequality, said policies had little success. The electorate, as always at major turning points, got again frustrated and wanted change, which politics provided. During Covid-19, stimulus cheques were sent directly to mostly lower- and middle class consumers, and various government programs were launched to support these demographics further, from tariffs on Chinese goods to the Inflation Reduction Act aimed at creating jobs in US manufacturing

Today’s post is the third in a series, with “Capital vs Labor (Pt.1)” in October ‘21 laying out why the Fed would hesitate to raise rates to rather risk running the economy hot than going back to the dreaded QE-years. “Capital vs Labor (Pt. 2)” in August ‘22 discussed how the structure of the labor market had changed and more real wage growth was likely. I’ve now revisited the theme as corporate profit margins, a proxy for the power of capital, appear to have reached an inflection point, with more downside likely ahead. While this has historically ended in employment losses, today’s post explores a silver lining for employees that may lead to a more benign outcome for labor

As always, the post concludes with my current outlook on markets. I still see a market that is very long equities, very short the US Dollar and very short volatility, and continue to be positioned on the other side of it

Before we dive into the matter of corporate margins, let’s briefly recall the typical cadence of an inflationary economic cycle:

Government prints money and gives it to consumer

Consumer spends printed money

No increase in productive capacity = companies raise prices to fulfil excess demand

Consumers now stretched (“everything is so expensive”) = corporate revenue growth slows

Corporate costs keep increasing, especially labor as consumers want to catch up

Revenues slow, cost up = margin crunch. Companies respond with layoffs

Economy slows, government answers with more printed money = cycle restarts

As previously discussed, the US economy is currently, likely, undergoing stage 4 & 5 of said cycle, which started with the ‘21 inflation surge in the wake of Covid-19

The reason for said inflation surge of course may be debatable. I increasingly see arguments again that it was after all mostly due to supply bottlenecks. But I would suggest the common sense test here:

Over Covid-19, ~>$3tr new money was printed and handed out to consumers. In addition, trillions of debt were refinanced at rock-bottom rates, locked-in for years. To me, that seems straight from the inflation textbook. Below chart illustrates the dramatic rise in checkable household deposits

Now, why was so much money printed in such a short time, by both the Trump and the Biden administration?

The answer, in my view, is simple. After a decade of deflationary policies favorable to asset owners, the electorate wanted a break from it and politics followed

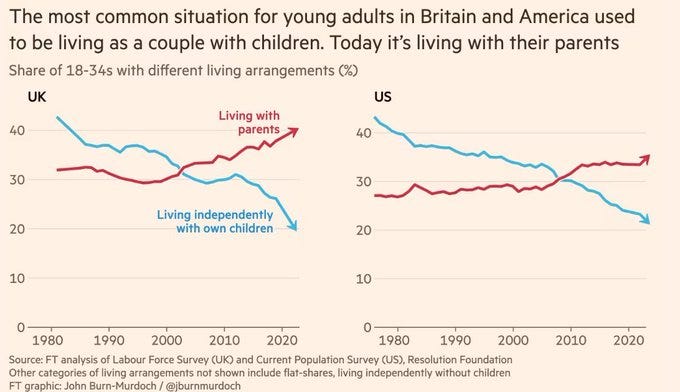

Few charts show this discontent better than the rising share of 18-34 year olds living with their parents, as the QE-driven rapid home price rise shut this demographic out of the housing market

Deflationary policies are great for corporate margins as labor has no bargaining power. Inflationary policies are the opposite. As the inflationary cycle progresses through time, we now see increasing evidence that corporate margins are getting hit (stage 4 & 5)

Let’s check in on the chart below that I already have shared recently. It uses the Fed’s preferred inflation metric Core PCE as proxy for corporate revenue growth, and Average Hourly Earnings as proxy for labor cost growth, together a proxy for corporate margins

Over the past two weeks, we got incremental data on both legs, Average Hourly Earnings as part of the NFP labor market data (+0.42%), and a close approximation of Core PCE via the December CPI and PPI numbers (+0.14%)

The gap continues to widen, suggesting increasing pressure on corporate margins. Indeed, this is translating to the bottom-up perspective, with the string of disappointing earnings releases continuing at a brisk pace

Just take the recent Delta Airlines update as an example - it is a mirror image of the discussed dynamics, with “fares softening” while wages are “pushed up”

Delta is not alone, in the past week alone companies such as Electrolux, Burberry, Atos or Dassault all reported similar results

Positive earnings surprises were hard to find year-to-date. US residential housing is an exemption, with homebuilder KB Home reporting a significant pick up in activity. See this post for more details why I remain doubtful that the goods economy can break the consumer-driven economic downtrend

Now, it has frequently been brought up that the US economy would be bullet proof due to the high deficit spend. But as I laid out in “From Secular Stagnation to Secular Reflation”, there are two financial engines to economic growth, fiscal spend and bank lending

Despite the substantial decline in interest rates since late October ‘23, bank lending growth has not picked up at all (orange line below). It is in fact now declining sequentially (see more details here)

So a likely slowing economy, no credit growth and likely declining corporate margins - does that mean we follow the historic playbook and employment losses are next?

This remains the likeliest case. However, there is a silver lining. There is one dynamic that could shift the odds in favor of labor, and either limit or possibly even avoid job losses - that dynamic is demographics

For the best part of the 20th century, the US population grew with >1% p.a.. Birthrates were high, as was immigration. This provided a constant flow of labor supply. But since the Great Financial Crisis, population growth has stalled

If we look further under the hood, a material imbalance appears. Baby boomers, a very large demographic cohort, are set to retire. The following generations are nowhere near as broad. As retired boomers continue to spend, but don’t work anymore, they remove more labor supply than consumer demand, possibly tightening the labor market in a secular way

Demographic change could be the wildcard that softens or even negates any substantial labor market weakness due to corporates fighting declining margins

This could possibly help rebalance the US economy towards a more even power distribution between capital and labor, after a 40-year one-way street towards capital, culminating in secularly high profit margins during Covid-19

The resulting real wage growth and possibly improved asset affordability could work to reduce the political tensions that went into overdrive over the past 5 years

Conclusion:

There are now more signs that a corporate margin crush is under way

As wage growth continues to run high, this moves a larger share of the economic pie from capital to labor, until employment losses start

The silver lining for employees may be that demographics changes labor market dynamics in their favor. This may limit or possibly even negate any material employment decline

What does this mean for markets?

The following section is for professional investors only. It reflects my own views in a strictly personal capacity and is shared with other likeminded investors for the exchange of views and informational purposes only. Please see the disclaimer at the bottom for more details and always note, I may be entirely wrong and/or may change my mind at any time. This is not investment advice, please do your own due diligence

My exposure continues to reflect the inverse of what I see as current market consensus, which I read as very long equities, very short the dollar, very short volatility and short energy. Accordingly, I am positioned for equity downside, energy upside and a move higher in volatility, in particular via:

Small long some producers of commodities with very tight supply/demand balances, hedged with a Russell 2000 short. I added to this in the past week long Oil Majors vs short Large Cap Tech (see last post) and today added some physical oil, as I find it more likely than not that the Middle East tensions increase from here

Equity downside exposure via US index put spreads with Spring expiry

Volatility upside via Vix call spreads with Spring expiry

Cash (i.e. T-bills)

Still looking for an entry into humanoid robotics over the coming weeks/months. Check out this video of a robot preparing a three-course meal, including breaking and stirring eggs (!). Medium-term, this will likely be a hugely transformational industry

As you can note, bonds are absent from the list above, as I do not see a clear message from them right now. However, I would note the following:

The very low December PPI reading suggests that Core PCE will come in at around ~0.14%. The Fed has also told us its framework for the pivot, which compares nominal rates to Core PCE and thus see real rates now as too high. The market has priced in cuts starting in March, which makes sense in light of the data

However, as the PPI release was published and the front end priced in the corresponding Fed reaction function, in response, US 10-year inflation expectations went up. The long-end went up with it. With this, the market is telling us for the first time that the Fed reaction function may be too dovish and imply higher inflation down the road

Should this dynamic persist, then I’d expect Fed speakers to walk back the amount of cuts priced in by the market for the latter half of this year. A lot will depend on how oil, and with it gasoline trades over the coming weeks and months. If inflation breakevens continue to rise, we have likely passed the point of “peak dovishness” for now

Thank you for reading my work, it makes my day. It is free, so if you find it useful, please share it!

Excellent piece as ususal!

Not sure those robots are ready for prime-time just yet:

https://twitter.com/tonyzzhao/status/1743378437174366715